What can be said about Martha Washington that hasn’t been thrown into the lexicon of American lore that we don’t already know about this American icon? Perhaps our first and only inclination of her reside with portraits of her in her elder years, looking every bit like someone’s grandmother. Or, perhaps you’ve heard of and even tasted a freshly baked pie named after her? She was married to George Washington, our nation’s first president; that must mean she was the first, First Lady, correct?

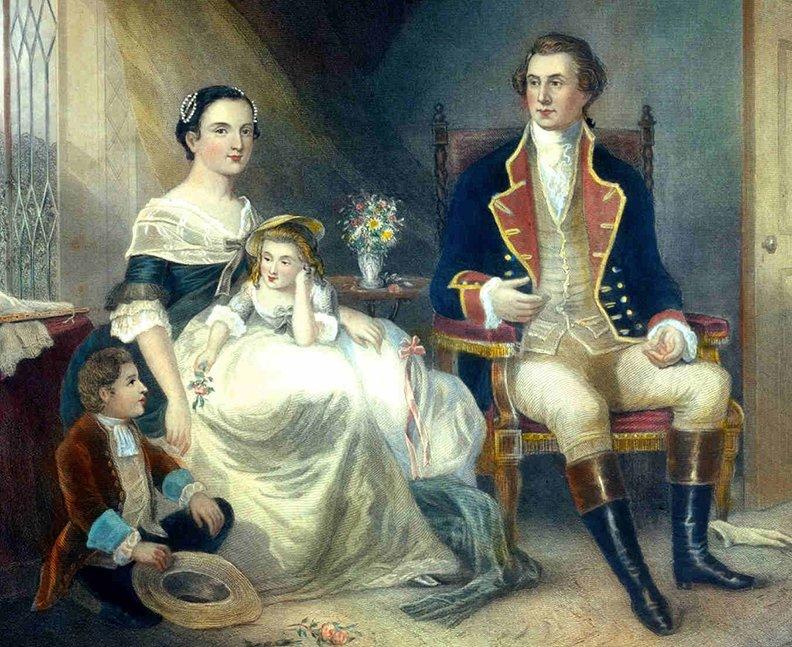

By all accounts, Martha Dandridge was a beautiful young woman. Born into the wealthy planter Dandridge family, she was one of eight legitimate children to John Dandridge and Frances Jones. She married the much older Daniel Parke Custis at the age of eighteen in 1750. Parke Custis was a wealthy planter with considerable landholdings. Martha suffered personal tragedies several times in her life. She had four children with Daniel before his death in 1757, but only two lived beyond the age of three. Of these, her daughter Martha “Patsy” was by all accounts a beautiful girl. Unfortunately, she suffered from epilepsy and died at Mount Vernon during a seizure in 1773 at the age of 16. Her other surviving child, John “Jackie” married Eleanor Calvert in 1774, and the two would give Martha four surviving grandchildren before the war’s end.

In 1758, Martha was courted by Col. George Washington, himself a wealthy planter in the Virginia tidewater country. Married on January 6, 1759, the two settled at Mount Vernon, with Martha bringing more than just her two children. She possessed over seventeen thousand acres of land and hundreds of enslaved people, all dwarfing Washington’s personal possessions. She was deeply devoted to Washington and fully supported him as the American Revolution broke out in 1775.

There is some dispute among historians over what camps Martha visited throughout the course of the war. Surviving documents and letters from personal friends do show her presence at the famous Valley Forge encampment during the winter of 1777-78. There she helped restore the confidence in her husband and presided over dinner functions with the wives of other officers. She was also present in New Jersey in 1783 as her husband navigated the disbanding of the army.

Following the war, Martha and George resettled at Mount Vernon, running the plantation and welcoming the revolving-door of guests who came to call on the retired war hero. They also became steadfast guardians and surrogate parents to Jackie’s two youngest children, Eleanor “Nelly” and George “Wash” Parke Custis. Their father, Jackie, had died of camp fever following the Siege of Yorktown in 1781. Martha, now having lost her last child, took on the role to raise her grandchildren. Jackie’s eldest two daughters, Elizabeth “Eliza” and Martha “Patsy,” remained with their mother, Eleanor Calvert Parke Custis, who would remarry in 1783 and bear sixteen more children in her lifetime.

When the Philadelphia Convention in the summer of 1787 called her husband away, and then seemingly placed him in a position to become the new nation’s first president, Martha was supportive but wary of leaving Mount Vernon. However, once relocated to New York City and eventually Philadelphia, she soon took on the role that would become First Lady by organizing weekly dinner parties and social gatherings that became the talk of the town. During the Washington’s tenure in Philadelphia, they brought enslaved people from Mount Vernon to perform the duties as servants in the president’s house. Among these were a young girl named Ona Judge. Judge had grown up as a playmate to Eleanor and became the personal body servant (someone who dresses and attends to personal matters) to Martha when she reached her teen years. When Martha’s eldest daughter Elizabeth was to marry in 1796, the First Lady planned to gift her daughter the young girl as a wedding present. Though it appears she was treated well (by her own accounts), Judge nevertheless was terrified that she would never gain freedom if she returned to Virginia. At the time, Pennsylvania law stipulated that any out of state enslaved person who remained present for more than six months would be legally recognized as free. To prevent them from losing their servants, the Washingtons developed a scheme to rotate their slaves in and out of Philadelphia every six months. Judge, being allowed to run errands in Philadelphia, probably gained this information from the city’s numerous free African American communities. With their help, Judge escaped one evening during dinner. She wound up in New Hampshire, where she successfully resisted pleas from the Washingtons to return. Though free, under Virginia law, she technically remained a runaway fugitive for the rest of her life. Years later, while speaking to a local newspaper, Ona Judge recalled that her desire to be a free person was stronger than serve a lifetime in slavery.

Following Washington’s retirement from the presidency in 1796, they returned to Mount Vernon where they continued to raise Martha’s grandchildren and run the plantation. Though it seems Martha did cherish her grandson Wash, the General was frank that the boy showed no focus or skill in education or an apprenticeship. Nelly married in February 1799, much to the joy of both of her guardians. In December, Washington fell ill after a horseback ride during a cold rainstorm. Upon his death, Washington directed that all his slaves be freed upon Martha’s death. It would appear Martha became quite alarmed of her situation. Fearing for her life, she decided to manumit the people in Washington’s will on January 1, 1801. Her health continued to fail her in the following year, and she died on May 22, 1802, at the age of 70.

Virginia’s slave laws stipulated that dower slaves, or those who were passed onto heirs after the death of the patriarch, could only be held in trust by Martha. After her first husband died, Martha inherited over three hundred enslaved persons. Legally, she had no control over them, i.e. she did not technically own the property. Her children and their heirs did. Washington himself was the legal guardian of the estate and holdings, but even he could not do much but hold the contract in trust until the grandchildren came of age. Most of the enslaved peoples at Mount Vernon were the dower slaves of Martha and her grandchildren.

Historians have debated how committed Washington was to emancipation. As he grew older, its clear the Founding Father first grew wary of the profession for economic reasons. As the principles of the American Revolution spread throughout the population, Washington seems to have changed his mind sometime in the early 1780s and began saying he wanted to rid himself of “this business” of owning people in bondage. Several of his closest military officers, particularly the Marquis de Lafayette and John Laurens, were emerging as dedicated abolitionists. In several letters, it appears Washington sympathized with abolition and agreed that slavery was wrong. However, he also strategically avoided making any public speeches or announcements regarding these views, most likely because he was more concerned about keeping the Union together and because it likely would have put him in a complicated domestic situation at home. Some historians have hinted at evidence that suggests Washington wanted to do more regarding slavery but was pulled back by his commitment to Martha and the Custis estate. It does not appear Martha shared his views on slavery. We may never know her true feelings because she burned most of her correspondence after Washington’s death in 1799. At this time, we simply do not know how she particularly felt regarding abolition, but we know Martha came from the wealthy Virginia planter society of the eighteenth-century, and she benefited and enjoyed the lifestyle that came with running a plantation worked by enslaved people.

When we view her legacy in American history, we can see how Martha Washington defined many of her time’s greatest qualities and strengths. In many ways, she showed the resiliency and fortitude women of the time did in fact possess. Upon the death of her first husband, she wielded immense monetary power and held thousands of acres of land on her own. This likely taught her how to manage and run a business, talents she employed later in life managing the household at Mount Vernon. On a domestic note, her recipes and cooking methods have produced countless successful cookbooks in American history. For those enthusiasts, her apple pies became a staple in American culture. Her presence alongside her husband during the American Revolution established a pillar of stability, whose physical and moral strength Washington relied on, and whose imagery was embraced by other wives and women of the age. In the 1780s, as the concept of republican motherhood blossomed, it was Martha Washington, whose fundraising during the darkest days of the war helped feed and clothe the army, inspired American women to become more involved in public and private life. Indeed, where Martha herself may have disagreed with some of the early suffragist’s grander plans, she nevertheless was an early influence on the expanding idea of what being an American citizen was supposed to mean. And we must recognize her contributions to this image, all the while as she continued to live a life of affluence, as someone who owned people. These contradictions must be understood, correctly. And we must recall that the Enlightenment provided many avenues of improvement, but society’s structures also remained frustratingly slow to adapt to these new principles.

Today, Martha rests next to the General in the tomb at Mount Vernon. Not far is a placard at the site of the unmarked graves of the plantation’s many enslaved peoples. In death, as in life, the contradiction is closely knitted to the American story, and it thankfully has been preserved for future generations. We must learn that many of our greatest citizens also were inconveniently human; who left legacies that reflect simultaneously through lenses of admiration and frustration. Indeed, the great balance in our history has always been trying to convey which emotion serves our interests more. It does us and them no good to close one eye in order to focus solely with the other. Having learned this, we should walk away knowing that maintaining the balance is our most important commitment as educated American citizens.

Further Reading

- First Ladies of the Republic: Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Dolley Madison, and the Creation of an Iconic American Role By: Jeanne E. Abrams

- George Washington’s Beautiful Nelly: The Letters of Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, 1794-1851 By: Patricia Brady

- Martha Washington: An American Life By: Patricia Brady

- The General & Mrs. Washington: The Untold Story of a Marriage and a Revolution By: Bruce Chadwick

- Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge By: Erica Armstrong Dunbar