On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant. With this surrender, other Confederate armies capitulated in short order, and the Civil War came to an end. Soldiers on both sides were discharged and returned to their homes. Now that the guns had been silenced, the lingering question remained: how do we move forward from here?

President Abraham Lincoln was grappling with that issue. Two days after Lee’s surrender, he delivered a speech on the “reconstruction” of the American States:

“By these recent successes the re-inauguration of the national authority -- reconstruction -- which has had a large share of thought from the first, is pressed much more closely upon our attention. It is fraught with great difficulty. Unlike the case of a war between independent nations, there is no authorized organ for us to treat with.”

This “Speech on Reconstruction” was his last public address to the people of the United States. In the crowd was John Wilkes Booth, who was angered at the outcome of the war and pledged to kill the President. On April 14, Booth shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. At 7:22 a.m. the next morning, President Lincoln died.

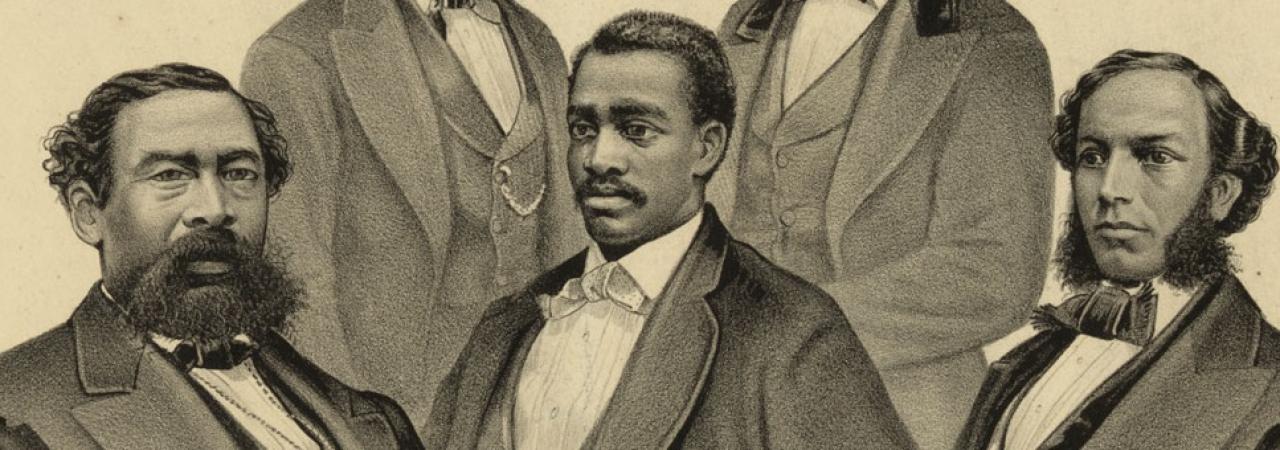

Hints of the Reconstruction that Lincoln wanted began during the war in 1863. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which gave freedom to all slaves in the areas that were in rebellion against the United States, and who worked under Confederate masters. (Note: slaves that were employed by Union aligned masters or in Union-aligned states were not Emancipated) This proclamation helped inhibit the Confederacy from obtaining legitimacy from foreign powers, such as England and France who were both antislavery. In addition, it, in theory, robbed Southern plantations and factories the free manpower needed to continue production in the South. Following this proclamation, African Americans from the North and South were recruited for the Union Army to form the United States Colored Troops division. These men were fighting for the continue emancipation of African Americans in all states.

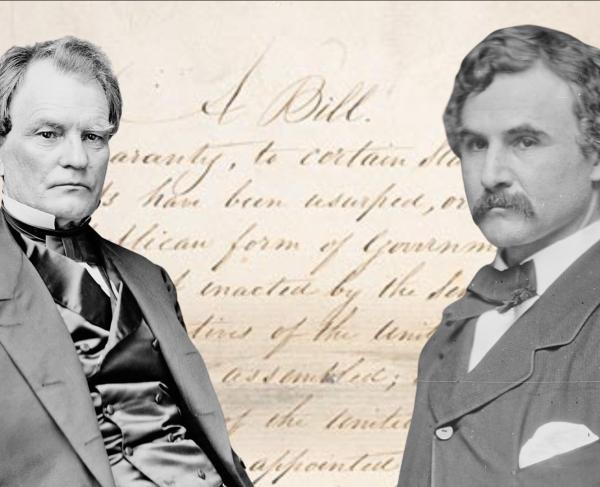

Because of this Emancipation, many abolitionist leaders and groups petitioned Lincoln to continue these effects. These effects resulted in the first of three, later named, Reconstruction Amendments that aimed to give equal rights and liberties to newly freed African Americans in the United States. The Thirteenth Amendment was passed by the Senate and the House on April 8, 1864, and January 31, 1865, respectively. However, President Lincoln did not see the ratification of this law. President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President and successor after his assassination, saw the ratification and adoption on December 18, 1865. The Thirteenth Amendment reads:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.,

With the Thirteenth Amendment, slavery as an institution was outlawed in the United States; however, it did so only to a certain degree. At the time, the caveat “except as a punishment for a crime” was non-controversial. Historically, prisoners had been punished with unpaid hard labor in the United States and abroad. However, including this stipulation allowed the South to re-enslave African Americans. The South created strict laws that disproportionally affected newly freed African Americans called Black Codes. The most common violation was “vagrancy,” which imprisons individuals for unemployment or for finding employment that was not as “legitimate” in the eyes of the law. There was no clear definition of “legitimate” employment, which allowed law enforcement to imprison anyone with little evidence of wrongdoing. Since many African Americans struggled to find employment after Emancipation, they were ripe for imprisonment from this charge. Once individuals were imprisoned, prisons sold the use of their “prison gangs” to plantations to harvest and plant crops. Ironically, while African Americans were now “free” many found themselves back on plantations working for no pay.

Seeing this abuse by the Southern States, the government set out to enact more legal protections for newly freed African Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was written to establish citizenship, without question, to newly freed African Americans. The Act, after it was ratified, stated:

“That all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power […] are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude[…] shall have the same right, in every State and Territory in the United States […] full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens […]”

However, when it was first written in 1865, this amendment was vetoed by President Johnson. Johnson believed that it “operate[d] in favor of the colored and against the white race.” This perceived bias, he believed, could set a precedent of legislation that discriminates one race in favor of another. Particularly, legislation that could discriminate against white people. Congress did not agree with this position and the veto was overridden. On April 9, 1866, the Civil Rights Act was enacted into law.

However, members of Congress worried that the Act did not give enough constitutional power to enact and uphold this law. They worried that, with no power backing, that Congress could not properly protect the citizenship of African Americans in the courtroom or with further legislation. Congress began meeting to establish the Fourteenth Amendment, the second of three Reconstruction Amendments, to help establish this citizenship. In addition, Confederate States were required to ratify this amendment, in addition to 10% of the population pledging loyalty to the Union, in order to be readmitted into the United States. Because of these stipulations, this Amendment was highly contested between the North and the South. Even with these debates, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed on July 9, 1868. The first section reads:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The first section of the fourteenth Amendment is the section that is the most quoted in subsequent judicial decisions. For example, in the landmark decisions of Brown v. Board of Education segregation was classified as “unconstitutional” because a “separate but equal” school system could never be truly equal and that this State-sanctioned inequality violated citizen’s rights to “life, liberty, or property.” However, the Supreme Court ruled that this Amendment only affected public entities and could not address the denial of citizenship or rights performed by private citizens. The subsequent sections regarding how Representatives shall be appointed (Section 2), the exclusion of individuals who have “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” from serving in Congress (Section 3), the refusal of Congress to pay for debts incurred from engaging in “insurrection or rebellion” (Section 4), and stating their power to enforce the legislation (Section5). While this amendment solidified that African Americans were citizens according to the law, it did not stop the harassment or discrimination against African Americans in everyday life.

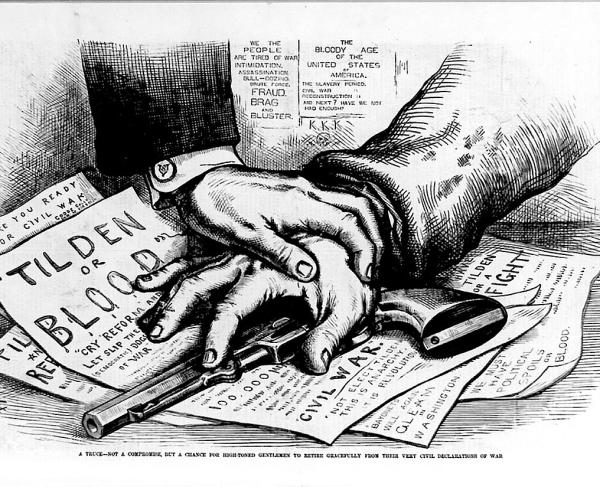

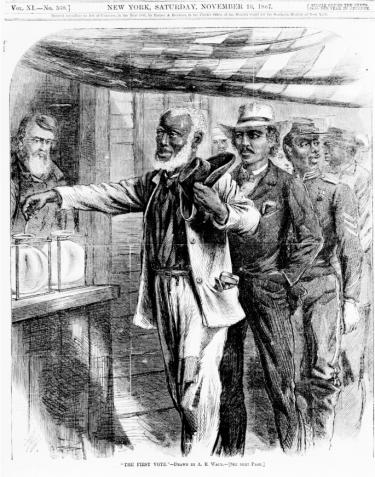

Much of this harassment played out in and near the voting booths. Voting laws were established to limit African American's ability to vote. With African American’s adoption as citizens, African American males could vote for the first time. Since Lincoln, who was a Republican, and a Republican Congress legislated Emancipation and citizenship to former slaves, most African American men voted for Republican candidates. Southern Democrats, worried that they could lose their elected seats, enacted convoluted laws to limit the amount of African American men who could vote. Laws were enacted that required all new voters to pass a literacy test before registration. Since education was illegal for slaves in the South, few former slaves were literate and could pass these tests. In order to not discriminate against poor white, illiterate farmers who usually voted Democrat, “Grandfather Clauses” were added to voting laws: if one’s grandfather had the right to vote, then their descendants had the right to vote regardless of other tests and limitations. If individuals were able to pass the literacy tests and the other stipulations in place, many African Americans were still wary or unable to vote. White community members verbally and physically harassed African Americans who tried to vote and threatened bodily harm against them, their children, their family, and their friends.

With the election of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 and these new challenges, Congress agreed that another amendment was needed. The last Amendment of the Reconstruction Amendments was adopted into law on February 3, 1870. It stated:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

With this Amendment, lawyers could argue that these exploitative voting laws were targeting African American voters and were unconstitutional by way of the Fifteenth Amendment. This amendment did not fully stop voting obstacles to certain groups being utilized but did make those obstacles unconstitutional.

No other amendments were added before Reconstruction officially ended in 1877. Overall, Reconstruction was a failure. Innovative legislation was not forthcoming to help ease the discrimination that many newly freed slaves felt in the South. However, the Reconstruction Amendments did their part: they officially ended overt slavery, gave citizenship to newly freed African Americans, and established the right to vote regardless of race.