The Battle of Bentonville

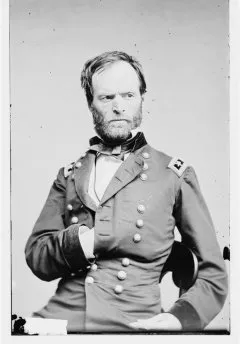

As the momentous year 1864 drew to a close, the Armies of the Union stood poised to deal their final blows to the Confederate war effort. Atlanta had fallen, President Abraham Lincoln had been reelected, and the Confederate Army of Tennessee had been soundly crushed. The western armies seemed unstoppable, as Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman presented Savannah, Georgia to Lincoln as a Christmas offering. Georgia howled, and the tide of war shifted permanently in favor of the North.

In Virginia, the Union general-in-chief, Ulysses S. Grant, was making plans. Having relentlessly pursued the Army of Northern Virginia, Grant was stalled against his old nemesis in the trenches around Richmond and Petersburg. Robert E. Lee's vaunted Confederate army, on its last legs after more than three years of brilliant campaigning, stood defiantly between Grant and the Southern capital.

Grant now wanted Sherman's men ferried by sea to Virginia, where their combined armies might administer the coup de grace to the South's principal army. Sherman, however, had been making plans of his own. On Christmas Eve, he coolly laid them out for his superior — an overland strike into the heart of the Confederacy with 60,000 men. It was vintage Sherman, and a proud Grant replied: "Your confidence in being able to march up and join this army pleases me . . . The effect of such a campaign will be to disorganize the South, and prevent the organization of new armies from their broken fragments . . . [M]ake your preparations . . . without delay. Break up the railroads in South and North Carolina, and join the armies operating against Richmond as soon as you can."

In mid-January 1865, as Sherman moved into South Carolina, the Confederacy received another irreversible blow when Fort Fisher — guarding access to Wilmington, N.C. — fell to the largest Union combined operation of the war. The amphibious attack sealed Wilmington's doom and closed the last major blockade-running seaport open to the South, choking Lee's supply line.

Against poorly arrayed Confederates under Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, Sherman's minions blazed northward virtually unopposed. By February 22, Columbia was ruined and Wilmington was in the control of Federal forces under Maj. Gen. John Schofield and Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry. With the beaten remnants of the Army of Tennessee and other Rebel units widely scattered across the South, only North Carolina lay between fast-moving Sherman and a junction with Grant's armies.

Schofield had direct orders from Grant to act in cooperation with Sherman's march. Their joint objective in North Carolina, as outlined by Grant, was the rail hub of Goldsboro. There, the combined armies (under Sherman) would secure a supply base to rest and refit before continuing the campaign.

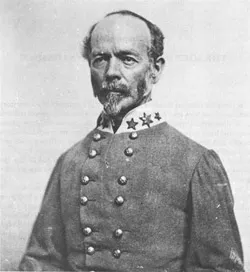

General Lee, newly appointed commander-in-chief of all Southern armies, lost faith in Beauregard and took his case to the Confederate War Department. Lee's choice for a replacement offered one of the sad ironies of the war for Jefferson Davis. With few options as the noose tightened on his dying nation, the Confederate president reluctantly approved Lee's candidate — a personal enemy Davis had sacked in Georgia seven months earlier.

Thus, on the day Wilmington fell, Lee wired Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at Lincolnton, N.C.: "Assume command of the Army of Tennessee and all troops in Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida . . . Concentrate all available forces and drive back Sherman."

Johnston knew it was too late to stop Sherman, and he told Lee as much. Even slowing the Union advance seemed a stretch at this point, given the far-flung units at Johnston's disposal. Reluctantly, the veteran commander assumed his final responsibility. Time was short, and "Old Joe" faced a daunting task.

As the Union army crossed into North Carolina on March 7-8, it was traveling in familiar fashion — two separate wings of roughly 30,000 men each, living off the land as they went. The march was a marvel of military engineering and logistics. Sherman knew that his "special antagonist" from the Atlanta Campaign had been restored to command. That first week of March, Sherman urged his top commanders to keep a sharp watch for enemy activity, and to prepare to fight Johnston if necessary.

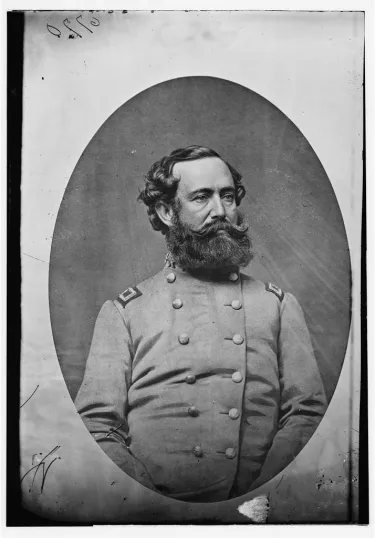

The Confederate commander was waiting at Fayetteville, where he informed Lee on the eighth that he would endeavor to strike a portion of the enemy's divided army. Evacuating Charleston and falling back through South Carolina, Confederate Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee's corps of seasoned veterans and raw garrison troops reached Fayetteville just one step ahead of Sherman. As the Federals approached town on March 10, the first indication of organized resistance came when opportunistic Rebel troopers under Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton mauled a portion of Maj. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry division. Hardee then withdrew northeast along the banks of the Cape Fear River and took position several miles south of Averasboro. Having left Fayetteville for Raleigh, Johnston directed Hardee to stay "as near the enemy's line of march as possible, which will enable us to unite [our] other troops with yours."

The Federals occupied Fayetteville on March 11, opening communication with Union forces at Wilmington. On the same day, Lee pushed Johnston: "You must judge what the probabilities will be of arresting Sherman by battle . . . A bold and unexpected attack might relieve us." At this point Sherman could practically taste his objective: Goldsboro. He wanted a clear road, and hoped Johnston would fall back to guard the capital city of Raleigh. "I can whip Joe Johnston," Sherman boasted to General Terry, "provided he don't catch one of my corps in flank, and I will see that my army marches hence to Goldsborough in compact form." As the army crossed the Cape Fear on March 14, Sherman reassured Grant: "The enemy is superior to me in cavalry, but I can beat his infantry man for man, and I don't think he can bring 40,000 men to battle."

On March 15, Lee again reminded Johnston of the dire situation facing both commanders. Laying a heavy load on his old friend and subordinate, Lee warned: "If you are forced back . . . and we be deprived of the supplies from East North Carolina, I do not know how [my] army can be supported . . . [Do not] engage in a general battle without a reasonable prospect of success . . . I shall maintain my position as long as it appears advisable . . . Unity of purpose and harmony of action between [our] two armies, with the blessing of God, I trust will relieve us from the difficulties that now beset us."

That day — as four Rebel commands gathered in North Carolina — Johnston traveled to Smithfield to form the hodgepodge Army of the South. After evacuating Wilmington in February and resisting Schofield at Kinston on March 8-10, Gen. Braxton Bragg finally had arrived at Smithfield with Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke's Division (Army of Northern Virginia). Hardee's Corps was hovering near Averasboro, gauging the advance of the Federal Left Wing. Hampton's cavalry was split to monitor both wings of Sherman's army. The proud remnants of the Army of Tennessee were slowly trickling into Smithfield from the west, having departed Tupelo, Mississippi, by rail in mid-January. Elements of these ragtag veteran units had arrived in time to fall back before Sherman in South Carolina, and to help against Schofield at Kinston. Others were still on the way.

As his motley units converged, Johnston waited anxiously for news. Was the enemy moving on Raleigh or Goldsboro? From his position at Smithfield, Johnston could swing west or southeast to block the way to either destination. Lacking sufficient numbers for a decisive engagement, however, Johnston needed favorable ground from which to tackle one wing of the Union army while the other was beyond supporting distance. The clock was ticking.

On March 16, Hardee's Corps fought a crucial delaying action with Sherman's Left Wing near Averasboro, buying a precious day's time for Johnston's gathering forces. The crisis of the campaign emerged when the aftermath of Hardee's engagement revealed Sherman's intentions. As the Left Wing turned east toward Goldsboro, Hampton fell back with Col. George Dibrell's cavalry division to Willis Cole's plantation, two miles south of Bentonville on the Goldsboro Road. Desperate for news, Johnston fired off inquiries to his subordinates. "Something must be done tomorrow morning," he pushed Hardee on March 17, "and yet I have no satisfactory information." He then queried Hampton for specifics on the enemy's position, strength, and relative distance. "[G]ive me your opinion," urged Johnston, "whether it is practicable to reach them from Smithfield on the south side of the [Neuse] river before they reach Goldsborough."

In the small hours of March 18, Hampton replied that Cole's Plantation — 20 miles south of Smithfield — would be the ideal location to block the Federal advance. The enemy was still a day's march away, and sufficiently separated from the Right Wing. Hampton was sure his cavalry could hold the ground long enough for Confederate forces to gather near Bentonville. The decisive moment had come, and Hampton's dispatch triggered Johnston's deployment. "[P]ut your command in motion for Bentonville by the shortest route," he ordered Hardee. Johnston then notified Hampton: "We will go to the place at which your dispatch was written."

Ever vigilant, Sherman worried about his situation that day. "I think it probable that Joe Johnston will try to prevent our getting Goldsborough," he cautioned the commander of the Right Wing, Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard. The Left Wing trains might be vulnerable, he explained, warning Howard not to stray too far "until this flank is better covered by the Neuse."

At the doorstep of the campaign's objective, however, it took little to sway the Union commander's thinking. Judson Kilpatrick promptly reported what Sherman wanted to hear. The enemy was retiring on Smithfield, Kilpatrick explained, and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler's Confederates had burned the bridge over Mill Creek. On Sherman's faulty maps, the Smithfield-Clinton Road — where the bridge was destroyed — appeared to be Johnston's only southern approach from the Smithfield area. It suddenly looked as though Johnston would fall back to cover Raleigh. Sherman's impatience was about to play directly into his old adversary's hands. From this point forward, "Uncle Billy" would hear nothing of the grave threat from the enemy.

By dusk, Sherman's army was within 25 miles of Goldsboro, and he was certain the Left Wing would reach Cox's Bridge on the Neuse the next day — a scant twelve miles from pay dirt. That evening, Hampton's troopers and artillery repelled a bold Union foraging party at the Morris Farm, just west of Cole's. The chosen ground was theirs. Unknown to the Federals, Johnston's infantry was fast bearing southward on a road that met the Goldsboro Road south of Bentonville — at Cole's Plantation. Despite Sherman's unshakable confidence, the Federal Left Wing was ripe for disaster.

On the bright Sunday morning of March 19, the Left Wing— commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum — pushed ahead on the Goldsboro Road. As the familiar rattle of musketry rolled up from the east, the commander of the Union Fourteenth Corps, Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, expressed concern over enemy opposition. Sherman quickly dismissed the notion, and reassured Davis there was nothing in his front but Rebel cavalry. The Union commander then rode away to join the Right Wing, which was traveling on a parallel course to the south.

Hampton's horsemen fell back before the Federal advance, drawing the Fourteenth Corps into the Confederate trap just as it was being set. Hoke's Division was waiting astride the Goldsboro Road and the Army of Tennessee filed into position to the north. As Brig. Gen. William Carlin's division deployed to clear the road, Hoke's Confederates unleashed a withering fire of musketry and artillery. The left half of Carlin's line scrambled for cover in a deep ravine, and Brig. Gen. James Morgan's Federal division soon joined on Carlin's right.

With Hoke blocking the road, Johnston deployed Lt. Gen. A. P. Stewart's Army of Tennessee as a striking force. The rugged veterans of disaster in Tennessee were eager for redemption. A soldier in Brig. Gen. Joseph Palmer's brigade recalled words of encouragement as a Rebel colonel rode down the lines: "Boys, you remember the 19th and 20th of September, 1863, at Chickamauga? Well, this is the 19th of March, and you may look out for some work to-day as hot as it was there."

Around noon, Carlin launched a probing attack to discover the strength of the enemy. This reconnaissance-in-force was mauled severely as it blundered into the entrenched lines of Bragg and Stewart. General Slocum had initially sent word to Sherman that all was well. By early afternoon, however, Slocum had received enough bad news to realize he was in trouble. "I am convinced the enemy are in strong force in my front," he notified Sherman, requesting immediate assistance from the Right Wing. "Johnston and Hardee are here."

Hardee's Confederates had been delayed in reaching the field, but the greenhorns of Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro's Division soon added their weight to the Rebel striking force. At 2:45, Johnston dropped the hammer on Slocum. With Hardee leading the charge in person, the Army of Tennessee launched its final assault. Shouting in defiance, "they came down on us like an avalanche," recalled a Union officer. Carlin's poorly deployed line broke almost instantly. Fleeing their breastworks, the ranks of Federal soldiers were cut to pieces as the men scrambled out of the ravine. The left half of Carlin's division went reeling backward toward the Morris Farm while the right half caved in on Morgan's division. The 19th Indiana Battery lost three of its four guns.

Following up their advantage, the screaming Rebels bore down on the Goldsboro Road and slammed into Brig. Gen. Benjamin Fearing's Union brigade, which had been hastened to the left to stem the tide. Fearing's line promptly crumbled under the onslaught and fell back to the west.

Around 4 p.m., Bragg's line attacked Morgan's division, and a furious, often hand-to-hand struggle erupted in the pines below the road. The remnants of Carlin's right flank were sent reeling into the swamps to the south. "It seemed as though all was lost," recalled a Union private, "and the rebellious hosts came pressing on." Fighting behind stout breastworks, the brigades of Brig. Gen. John Mitchell and Brig. Gen. William Vandever struggled to hold on. They repulsed Hoke's Division, only to find elements of the Army of Tennessee (having knocked Fearing out of the way) moving on them from the rear. A determined counterattack helped secure their position, as Brig. Gen. William Cogswell's Twentieth Corps brigade lumbered through the swamps to Morgan's assistance. "Our loss here was heavy," noted a Rebel private. "They gave us credit for fighting them as hard as they were ever fought." An extended engagement ensued as Cogswell's men moved into position, and the surrounding woods caught fire. "It was a hot old time," recalled a solider in the 2nd South Carolina, "and things were lively if they were not lovely."

Late in the afternoon, the Confederates reached their high water mark as portions of the Army of Tennessee and Taliaferro's Division hurled themselves against the Union Twentieth Corps at the Morris Farm. Brig. Gen. James Robinson's brigade and massed Federal artillery repelled wave after wave of attacking Confederates. "Smoke settled down over the guns as it grew dark," observed a war correspondent, "and the flashes seen through it seemed like a steady, burning fire." Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws' Division (Hardee's Corps) arrived too late to be of real assistance, having spent much of its time out of action on Bragg's left. Early in the fight, in a tactical blunder that robbed the Confederate striking force of much-needed weight, Johnston had sent McLaws to Bragg's assistance where he sat idle for much of the day. Nevertheless, Johnston had given the Federals a serious drubbing — leaving a scar on Carlin's psyche the man would carry for the rest of his life. Having failed to completely crush the Union lines, the exhausted Southerners pulled back to their original positions. On the Morris Farm, General Slocum sent a final plea to Sherman for assistance.

All day long, the troops of Howard's column had heard the ominous rumble of battle in the distance, but Sherman had remained skeptical. As late as 5 p.m., he confided to General Kilpatrick: "Slocum thinks the whole rebel army is in his front. I cannot think Johnston would fight us with the Neuse to his rear." Yet the truth was undeniable. Sherman finally yielded to the reality of Slocum's predicament, and reassured his wing commander that help was on the way.

The Right Wing swung northward and westward via Cox's Crossroads early on March 20. Sparring with elements of Hampton's cavalry in a running fight, Howard's column began arriving on the battlefield by midday. Sharp skirmishing prevailed, as the Confederates changed position to deal with Howard's arrival. Johnston had managed to field only about 16,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry; despite receiving limited reinforcements, the Confederates were now woefully disadvantaged. Johnston clung to a tenuous bridgehead guarding his army's sole escape route over rain-swollen Mill Creek, and began evacuating his wounded to Smithfield.

To Sherman's great irritation, the Confederate army was still in position on March 21. Johnston — outnumbered and no longer holding the advantage of surprise — could only hope the Federals might be lured into a costly frontal attack on his small but well-entrenched army. That afternoon, in the midst of a soaking downpour, a "little reconnaissance" by Maj. Gen. Joseph Mower's Seventeenth Corps division escalated into a full-scale push toward Mill Creek Bridge on the weak Confederate left flank. Mower's advance overran Johnston's headquarters, forcing the general and his entourage to beat a hasty retreat. A last-ditch counterstroke led by General Hardee enveloped Mower's two brigades and forced them back. Sherman was furious over Mower's action, fearing it would bring on the general engagement he desperately wanted to avoid. The Union commander called Mower off, but not before his men had been roughly handled by the Confederates. Johnston gambled in stripping his right flank to protect his left, and Hardee's bold action saved the bridge. With no further advantage in remaining at Bentonville, the weary Confederates abandoned their works during the night and withdrew toward Smithfield. On March 22, Federal forces pursued the enemy as far as Hannah's Creek before giving up the chase.

The battle claimed roughly 4,500 casualties on both sides. Indeed, the human cost in North Carolina was high. When combined with other major engagements fought that bloody March — Monroe's Crossroads, Averasboro, and Wyse Fork — the number of combat casualties of all types approached 9,000 men (not counting losses suffered in various skirmishes along the way).

From Savannah to Goldsboro, Sherman's juggernaut had covered 425 miles of hostile territory. Joe Johnston marveled that "there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar." Sherman himself viewed the storied March to the Sea as mere "child's play" compared to his Campaign of the Carolinas.

Jefferson Davis had smugly predicted that Johnston would retreat before Sherman all the way to Virginia. Given his well-known penchant for inaction, why did Johnston fight at Bentonville? The general later claimed he hoped to achieve fair terms of peace. But as much as anything, Johnston had thumbed his nose at Davis and embraced the confidence held in him by Lee. Despite inherent obstacles and tactical blunders, Johnston's eleventh-hour troop concentration and the resulting battle at Bentonville were the most decisive actions undertaken by "Old Joe" during the war. In a losing effort, Johnston ably reminded Sherman that the Confederates were still to be reckoned with in the spring of 1865. Indeed, Sherman was fortunate that Johnston could effect only a partial concentration of his forces before giving battle.

The whole affair greatly bothered "Uncle Billy." His passion for occupying Goldsboro had clouded his cautionary judgment. Stung by the damage inflicted on the Left Wing, Sherman attempted to pass Bentonville off as a mere skirmish — much to the irritation of many a Union veteran who lost comrades in a full-scale action so near the war's end. Having been drawn into battle, and massing superior numbers, Sherman failed to finish the job. He erred in not bagging Johnston's army on March 20-21. With the godlike knowledge of hindsight, it is all too tempting for historians to anoint Sherman as a lofty "angel of peace" for allowing Johnston to escape. Militarily, however, it was an unsound decision. The Confederate army slipped away intact, enabling it to join with other Confederate forces in the field. Sherman was all too happy to oblige, preferring to deal with Johnston only after refitting his battered army at Goldsboro. Thus a Confederate threat still loomed to the west, and Sherman fully believed that he or Grant would have to engage in "one more desperate and bloody battle" with the enemy — perhaps against Lee and Johnston combined. "I rather supposed [such a battle] would fall on me," the general noted, "somewhere near Raleigh."

Sherman could have closed the lid decisively on Johnston at Bentonville — almost certainly with far less bloodshed than he might have faced in his predicted final showdown. As events unfolded, however, Sherman's war ended under far more favorable circumstances.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...