Painting of Molly Pitcher firing a cannon at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778 by E. Percy Moran

Women played critical roles in the American Revolution and subsequent War for Independence. Historian Cokie Roberts considers these women our Founding Mothers.

Women like Abigail Adams, the wife of Massachusetts Congressional Delegate John Adams, influenced politics as did Mercy Otis Warren. It was Abigail Adams who famously and voluminously corresponded with her husband while he was in Philadelphia, reminding him that in the new form of government that was being established he should “remember the ladies” or they too, would foment a revolution of their own. Warren, just as politically astute as Adams, was a prolific writer, not only recording her thoughts about the confluence of events swirling around Boston but also dabbling in playwriting. She was a fierce devotee to the patriot cause, writing in December 1774, four months before the war broke out at Lexington and Concord, “America stands armed with resolution and virtue, but she still recoils at the idea of drawing the sword against the nation from whence she derived her origin.” In 1805 she published History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution.

Women often followed their husbands in the Continental Army. These women, known as camp followers, often tended to the domestic side of army organization, washing, cooking, mending clothes, and providing medical help when necessary. Sometimes they were flung into the vortex of battle. Such was the case of Mary Ludwig Hays, better known as Molly Pitcher, who earned fame at the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. Hays first brought soldiers water from a local well to quench their thirst on an extremely hot and humid day and then replaced her wounded husband at his artillery piece, firing at the oncoming British. In a similar vein, Margaret Corbin was severely wounded during the British assault on Fort Washington in November 1776 and left for dead alongside her husband, also an artilleryman, until she was attended by a physician. She lived, though her wounds left her permanently disabled. History recalls her as the first American female to receive a soldier’s lifetime pension after the war.

Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved African American living in Boston, took up the pen and wrote poetry, becoming one of the first published female authors in America and the first African American woman to be published. Her 1773 collection Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Her poems focused on patriotism and human virtues. She even wrote a poem about George Washington, “To His Excellency, George Washington” in 1775, which she personally read to him at his Cambridge headquarters in 1776 while he was with the Continental Army in Massachusetts besieging the British. Her visit was the result of an invitation from Washington. Wheatley obtained her freedom upon the death of her master in 1778.

New York teenager Sybil Ludington, was the female equivalent of Paul Revere, though she rode twice as far as Revere and in a driving rainstorm in April, 1777. Her ride took her through Putnam and Dutchess Counties, New York where she roused local militia to fight a British force that had attacked nearby Danbury, Connecticut. The Daughters of the American Revolution erected a heroic equestrian statue to Ludington in Carmel, New York along the forty-mile route she traveled.

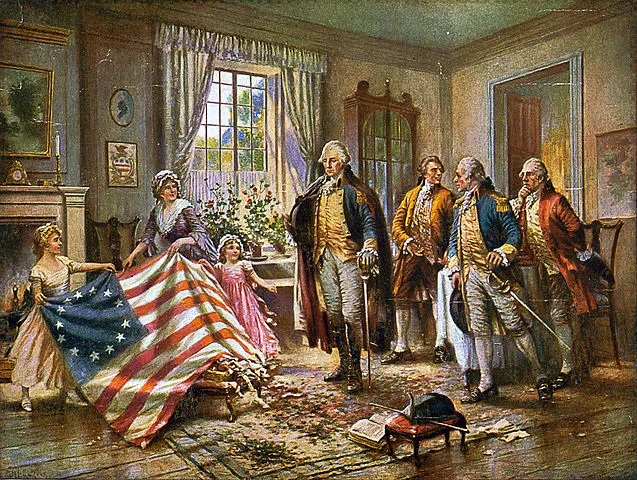

The story of one of the most famous revolutionary women, Betsy Ross, is likely just that - a story. Ross is often credited with sewing the first American flag, thirteen red and white stripes with thirteen stars in a field of blue in the corner. Subsequent research, however, shows that the story only surfaced around the Centennial, 1876, and was promoted by Ross’s grandson William Canby. Given that Congress passed the Flag Act in June of 1777, nearly a year after Ross is purported to have made the flag, the story is likely apocryphal.

As wives of the common soldier often followed the Continental Army so, too, did the wives of general officers. General Henry Knox, the Continental Army’s Artillery Commander married the vivacious and popular Bostonian Lucy Flucker, the daughter of Bostonian Loyalists. Once she and Henry were married, all ties between her and her family were cut. Henry and Lucy were devoted to one another and she would join him whenever she could while he was on campaign. She endured the bitter encampment at Valley Forge and became fast friends with the wife of General Nathanael Greene, the equally popular Kitty. George Washington’s wife, Martha Custis, spent every winter with her husband wherever the army was camped. In fact, once George Washington left his beloved Mount Vernon estate in 1775 to attend the 2nd Continental Congress in Philadelphia, he did not return to his home until 1781, as the combined American and French Army maneuvered south from the city of New York to Yorktown, Virginia, where the war was eventually won. The wives of generals were as equally helpful in matters of caring and providing compassion to sick and wounded soldiers, as were the wives of the common soldiers.

Ordinary women also endured the horrors of the battlefield when those fights came to their doorstep. Sally Kellogg of Vermont and her family escaped the gods of War in 1776 when the War for Independence found its way into the northern reaches of upstate New York and Benedict Arnold’s makeshift fleet and the British Navy clashed on Lake Champlain during the Battle of Valcour Island. As the Kellogg family made good its escape by water, Sally’s family “fell in between Arnold’s fleet and the British fleet,” she later recalled. As the family rowed to safety at Fort Ticonderoga, the exchange of gunfire between ships could be seen and heard Sally recalled, “but happy for us the balls went over us. We heard them whis.” Nevertheless, the war continued to follow the Kellogg family. A year later, after having relocated to Bennington, Vermont the Kelloggss were once more forced to be witnesses to carnage and once again upon recollection Sally claimed the results were, “a sight to behold. There was not a house [in Bennington’s vicinity] but was stowed full of wounded.

Not unlike women eighty years later who disguised themselves as men to serve in the armies of the Civil War, women of the Revolutionary Era also itched to get into the fight, do their part for the cause, and be engaged in a historical moment. One of the best examples of a woman who disguised herself as a man to fight in the Continental Army was Deborah Sampson from Uxbridge, Massachusetts. Amazingly, she also has a paper trail concerning her combat service in the army, where she fought under the alias of Robert Shurtliff, the name of her deceased brother, in the light infantry company of the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. She mustered into service in the spring of 1782 and saw action in Westchester County, New York just north of the City of New York where she was wounded in her thigh and forehead. Not wanting her identity to be revealed during medical care she permitted physicians to treat her head wound and then slipped out of the field hospital unnoticed, where she extracted one of the bullets from her thigh with a penknife and sewing needle. The other bullet was lodged too deep and her leg never fully healed. Her identity was finally revealed during the summer of 1783 when she contracted a fever while on duty in Philadelphia. The physician who treated her kept her secret and cared for her. After the Treaty of Paris, she was given an honorable discharge from the army by Henry Knox. Like other veterans of the Continental Army, she was continually petitioning the state and federal government for her service pension. She later married and had three children settling down in Sharon, Massachusetts. To help make ends meet she often gave public lectures about her wartime service. By the time she died in 1827, she was collecting minimal pensions for her service from Massachusetts and the federal government. In her memory a statue stands today outside the public library, in Sharon, honoring her Revolutionary War service and sacrifices.

Many women of all stripes and from all backgrounds recognized the value of the American cause and stepped up to serve the cause of the new nation as best they could.

Further Reading:

- Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence By: Carol Berkin.

- The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America By: Robert M. Dunkerly.

- Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation By: Cokie Roberts.

- Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral By: Phillis Wheatley.