The Civil War began early and ended late for John Grimball. His unique career at sea in the Confederate Navy would span nearly five years of service in a war that lasted four on the ground.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina in April 1840, John (or Jack, or sometimes Johnnie to his friends) was the fourth son in a well-to-do planter family. His father, John Berkeley Grimball, had graduated from Princeton and grew rice at his Pinebury Plantation between Charleston and Savanah. In 1830, the elder Grimball married Margaret Morris, whose family owned the nearby Grove Plantation. John inherited the Grove from his wife’s family in 1858, and they owned several slaves to work their rice fields along the coast. John Berkeley Grimball became a South Carolina state senator and cast his vote for secession in December 1860.

Young John left home at the age of 14 to join the Navy. He earned an appointment to the U. S. Naval Academy, graduating in 1858 (14th out of 15 in his class). On Christmas Eve, 1860, just four days after South Carolina’s withdrawal from the Union, Lieutenant Jack Grimball resigned his U. S. Navy commission and offered his services to South Carolina governor Francis Pickens. Four of Grimball’s brothers joined Rebel infantry or artillery units, one dying of typhoid fever in 1864.

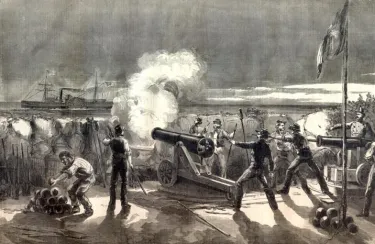

Grimball’s first posting was to Fort Moultrie on the east shore of Charleston Harbor. The fort had been occupied by Union troops until late December, when the garrison was moved to nearby Fort Sumter in the center of the harbor. Sumter offered better protection from a Rebel attack, but was isolated and had to be resupplied by ships. By January, Sumter was running out of provisions. The administration of outgoing President James Buchanan ordered that a civilian merchant ship instead of a U. S. Navy vessel be sent with supplies to the fort, so as not to anger Charleston’s hot-headed defenders. Grimball and others manned heavy guns that now encircled the Union-held fort.

On January 9, 1861, the steamer Star of the West approached Fort Sumter with food and supplies. At dawn, as the ship crossed the bar and entered the harbor, Rebel guns on Morris Island, crewed by cadets from the nearby Citadel, opened fire. Bracketed by shell splashes, Star of the West turned around and hoisted her colors. As the ship turned in the channel, Grimball’s guns and others from Fort Moultrie fired on the vessel. Star of the West was lightly damaged in the attack, struck twice inconsequentially by shells. The brief engagement, which some consider the first shots of the Civil War, predated the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter by three months. Jack Grimball was in the war before it began.

After the fall of Fort Sumter, Grimball received a commission as a lieutenant in the Confederate Navy. He helped recruit new seamen and briefly served on the Lady Davis, a small two-gun vessel helping to defend Charleston Harbor. In July 1862, Grimball received orders to the new ironclad CSS Arkansas, then just entering service on the Yazoo River in Mississippi. On July 14, 1862, the Arkansas and other Confederate craft were ordered to pass through Admiral David G. Farragut’s naval force on the Mississippi River at Vicksburg. As the vessel moved down the narrow Yazoo toward the Mississippi, large trees on the banks hung over the channel, threatening the high smokestack of the oncoming and not very maneuverable ironclad. On his own initiative, Grimball sprang ashore and quickly tied a line from the ship to a tree, slowing the Arkansas and pulling it out of harm’s way. The next day, Grimball led several men manning one of the ironclad’s 8” smoothbore bow guns as Arkansas ran through Farragut’s fleet. Arkansas was attacked again that night as Farragut’s ships ran downriver past the Vicksburg batteries: 12 men on the ironclad were killed and 18 were wounded, several from Grimball’s gun crew.

That August, after the Arkansas was scuttled to prevent her capture, Grimball was sent to the cotton clad ram CSS Baltic in Mobile Bay. Baltic was not well designed, lightly armored, and could not offer much to the defenses of the city. Grimball left the Baltic before Farragut’s campaign against Mobile Bay got underway in mid-1864.

Around that time, Grimball was ordered to Europe. By 1864, the Confederacy had begun to feel the effects of the U. S. Navy blockade of Southern ports. A limited amount of military equipment could get in, and virtually no cotton or other cash crops could get out to be sold abroad. Hoping to draw the attention of Union warships away from the coasts and out to the high seas, the Confederates covertly ordered a handful of seagoing commerce raiders to be built or converted in private shipyards in Great Britain. The ships were outfitted as merchant vessels, then were sent to neutral anchorages where they were converted to armed cruisers manned with Confederate Navy personnel. Grimball and other officers were sent to man the ships as they departed British shipyards.

Grimball was in the French port of Cherbourg on June 11, 1864, when the commerce raider CSS Alabama arrived for a much-needed refit and resupply. Alabama had just completed a two-year voyage during which she captured or destroyed 65 Northern merchant ships. Grimball and another officer volunteered to serve onboard Alabama if needed, but the French authorities, strictly adhering to neutrality rules, prohibited them from joining the ship’s crew. Eight days later, the Alabama met the USS Kearsarge in battle just off the Cherbourg harbor entrance and was sunk.

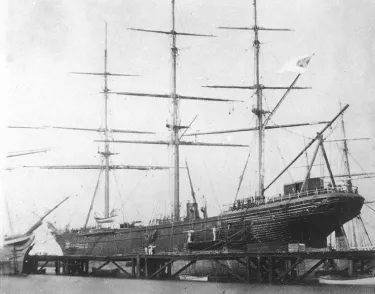

Grimball soon received another assignment. He was ordered to Liverpool, England where the officers assigned to the newest Confederate raider were gathering. Wearing civilian clothes and avoiding watchful Union diplomatic authorities, Grimball and the other officers quietly slipped aboard a supply ship ordered to rendezvous with the new raider in the Azores. On October 9, the ship left Liverpool and eight days later met the vessel, still configured as a merchant ship, in the Madiera Islands. Both ship’s crews worked quickly to convert her into an armed warship, and when the work was completed she was commissioned the CSS Shenandoah.

Grimball was one of five lieutenants in the Shenandoah’s crew, all five came from prominent Southern families, and most had been former U. S. Navy officers. Grimball frequently led boarding parties that captured the crews of the U.S.-flagged ships encountered at sea. Once the crews were removed, most of the vessels were burned rather than sent into port as prizes. The high-seas menace of the Shenandoah, by now the last of the Confederate commerce raiders, inspired Southerners everywhere toward the end of the war. Shenandoah and her crew cruised for thirteen months, destroying 32 vessels under the Yankee flag with an estimated value of $1.4 million. She traveled from the Cape of Good Hope to the Arctic Ocean, from the South Pacific to the North Atlantic, and was never opposed by a U. S. Navy warship. As the Confederate cause evaporated, Shenandoah was regarded by many as a pirate ship. Grimball later remembered: “I always felt that whenever our nationality was known to neutral ships, the greetings we received rarely warmed up beyond that of a more or less interested curiosity, and while we had many friends ashore who were most lavish and generous in welcoming us to port, underlying it all there appeared to exist a wish of the authorities to have us ‘move on.’” The ship operated into the summer of 1865, weeks after the collapse of the Confederacy and most of its armies. The crew heard of the surrenders from ships they encountered but dismissed them as unconfirmed rumors.

On June 28, 1865, five days after the surrender of the last Confederate army, on what would be the most lucrative day of her career, Shenandoah encountered nine New England whaling ships working together in the Bering Strait. Slowly approaching the group under a U. S. flag, Shenandoah put boats in the water with armed boarding crews. As the whalers realized there were Confederate officers approaching, they began to maneuver away. On the Shenandoah, the officer of the deck at that moment, John Grimball, let the U.S. colors fall, hoisted the Confederate flag, and ordered a warning shot fired across their bows. It would be the last shot fired by the Confederacy.

Two months later, Shenandoah confirmed news of the end of the war from a British vessel. Without a country, she began her long voyage home – wherever that might be for a Confederate warship that had never docked in a Confederate port. Deciding to surrender his vessel to a neutral country, her captain set a course for Liverpool where the ship arrived on November 6, 1865. There, her flag was lowered for the last time. The Civil War was over.

Grimball and some of the other officers feared reprisals from the U. S. government. Grimball fled to Mexico where he worked for a time on a ranch. The fears of revenge were unfounded, so he returned to the U.S. after a year in exile. He began a career in law, practicing first in Charleston then in New York City. He returned to Charleston in the 1880s and began a family, eventually having four sons.* He died in 1922 at the age of 82 and is buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston.

Giving a speech about his time on the Shenandoah long after the war, John Grimball quoted a writer of the time. “The last act in the bloody drama of the American Civil War had been played. Widely different were the armies that witnessed the opening and the closing scenes. The overture was played by the thunder of artillery beneath the walls of Sumter, with the breath of April fanning the cheeks of those who acted their parts while all the world looked on. The curtain finally fell amid the drifting ice of the Arctic seas." Jack Grimball had witnessed the opening scene of the war, and he was there, too, when the curtain finally fell.

* John Grimball’s grandson, named for his grandfather, was a second lieutenant in the U. S. Army in Germany in 1945. He was a tank battalion commander and earned a Silver Star at the Battle of the Bulge, and a Distinguished Service Cross for his role in the capture of the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine that March.

Further Reading

-

War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865 By: James M. McPherson

-

Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History By: Richard Snow

-

Lincoln and His Admirals By: Craig Symonds

-

The Civil War at Sea By: Craig Symonds