The Conspirator

The Civil War Trust recently had the opportunity to speak with Robert Stone, a producer of the American Film Company movie, The Conspirator, which tells the story of the Mary Surratt, the only woman charged in the plot to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

Civil War Trust: Tell us a little bit about the mission and goals of the American Film Company.

Robert Stone: The American Film Company was founded for the specific purpose of producing feature films that are set in American history and are accurate to the period, but are also compelling stories. Its founder is Joe Ricketts, who started Ameritrade, and The Conspirator was our very first project. We’re not a “development company,” so we don’t spent money developing screenplays. We began with a strong belief that there are a lot of screenplays out there collecting dust that are set in our past and are accurate — or close enough that we can remedy them to suit our tight mandate — and also have the potential to be hugely entertaining and provocative films. When we started, we were faced with something of an archaeological dig to find quality American history content. The Conspirator was one of the first 20 to 25 scripts that we read, and it really stuck with us. Even when we’d reviewed 300 or more screenplays, we kept coming back to it.

Why is that – what aspects of this story drew you in?

RS: Everyone knows the story of John Wilkes Booth — or, at least they think they do. Few people are aware of the bigger conspiracy to decapitate the government. While it was, unfortunately successful in killing Lincoln, it was unsuccessful in its full intent. The appeal is that it’s associated with one of the most historical events in our nation’s past, and yet it’s a story that most people aren’t aware of. We held a number of screenings that either a producer or screenwriter attended, where we actively looked for history lovers to attend. Overwhelmingly, the response was that “Wow I didn’t know” or “I knew that once, but had forgotten.” This isn’t what’s covered in your high school history texts — it’s an interesting way to tell the story with a very human angle, with Mary Surratt and the almost Sophie’s choice aspect of her trial. Plus, telling the story from a backdoor angle was ideal. We’re not big enough to tackle the whole Lincoln story head on, so we had to find an innovative way to tell and make people care.

Tell us a little more about that “backdoor angle.”

RS: It’s one of the things that attracted us to the script so profoundly. We didn’t want to present a biased view of whether Mary Surratt was guilty or innocent, or to bias viewers. We wanted a story that dealt with the circumstances, the time and the trial itself. The downside is that Robin Wright doesn’t get a lot of lines, that we don’t hear her opinions, because the story is of her through Aiken. What we hear are the thoughts and impressions of an outside source and he sifts through it all. And I think a lot of different audiences were able to appreciate how the story was told — it meant we didn’t have to butcher the history to tell a Hollywood version.

One of the American Film Company’s main goals it to produce historically accurate films, but some history-lovers can be quite fanatical about the minutest details. How did you cope with those kinds of demands?

RS: It was definitely one of the issues that we faced! That passion was very evident in the screenings we did where a few folks would try to call out what they thought was inaccurate, usually things like the piping on a uniform or buttons. Or a flush toilet that was used in a particular scene! We did tour research, though, and that particular building was one of the first to have a flush toilet and had it at the time. There were very few that actually put chinks in our armor of representing the history as accurately as possible based on our budget and availability. For example, we shot the film in Savannah, Ga., because historians agree that it most accurately reflected the architecture of the period. Fort Pulaski filled in for the arsenal penitentiary because it’s similar in construction and look, but some people complained that the original site didn’t have a moat. Well that building doesn’t exist anymore, and we couldn’t alter Fort Pulaski that significantly, plus we didn’t have the budget to do so anyway. We thought a period fort better than a sound stage, so we did everything we could. The gallows were built to the specs of the original design, including carpenters nails from the period, for example. At the end of the day, the purpose isn’t to educate professional historians, it’s to engage the audience and tell an interesting and compelling story through historical events.

What do you hope that viewers will take away from the film?

RS: I hope that people come away with a new understanding and interest in the events portrayed in the Lincoln assassination. I hope that people do more than read the names in a text book, that they realize those were real people with emotions and motivations that might not have made History 101. I know a lot of people believe the purpose of the film was to make a political statement about modern times. But really, I think the story is an indication of how different things are now, rather than how similar. It’s not about how history repeats itself, but what we can take away from the past to better understand the present.

Can you tell us about any of your upcoming projects?

RS: The stories right now on our front burner amount to some of the great “triggering events” in American history. Take Paul Revere and his midnight ride; while most people think they know the whole story, there are other riders from that night who have gone uncelebrated. That one will be different in feel from The Conspirator — it’s a really fun swashbuckler! There’s no literal fencing, but it feels like there’s swordplay going on. It’s based on book by Pulitzer winning historian David Hackett Fischer, essentially the definitive Revere biography, so it’s really fun and still remains quite faithful to history. When we were initially researching screenplays, we found quite a number about John Brown. But all were very epic in scope, either portraying him as a great hero or the demonized antagonist. So this is the one script we’ve developed as a company and it focuses on the few days most critical to the story of John Brown in October 1859. At its core, it’s a hostage movie — like Dog Day Afternoon, set at the Harpers Ferry arsenal. We just hope that doing it after doing The Conspirator doesn’t make us known as the company that only makes Civil War films that end in hangings!

Now that The Conspirator is out on DVD, can you tell us anything about the special features included on the release?

RS: The DVD includes a lot more than just the film, there are a lot of really colorful details. There is a 67-minute documentary on the plot to kill Lincoln, plus a variety of short featurettes that cover the production process and interview the cast and crew, but also get into very pointed issues about history: Guilty or innocent? How was the sentence carried out? These are the sort of compelling nuggets that help flesh out the full story beyond sitting in the movie.

And then there’s Robert Redford’s commentary! He could read the phonebook and I could watch all afternoon. But here he has some really tremendous insight into the story, the characters and their place in history.

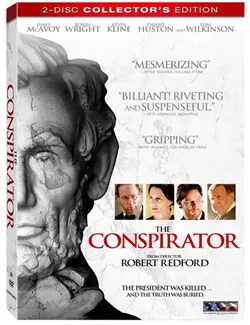

Buy the Movie: The 2-disk Collector's Edition of "The Conspirator" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore