Continental Congress

On September 5, 1774, delegates from twelve of the thirteen British colonies of North America met in Carpenters’ Hall located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. These fifty-six men met to discuss the British blockade of Boston Harbor and the Intolerable Acts instituted by King George III. From different walks of life, the delegates found commonality in their anger and frustration at the precarious political and economic situation that the colonies were in. For weeks, they discussed a collective action against Britain to vocalize their displeasure against the blockade and these Acts. This meeting was the meeting of the First Continental Congress. However, this meeting was not the first time that the colonies had collaborated to institute rights for themselves, and, to some of their dismay, this meeting was not the last.

The first proposal for an official colonial-wide union was introduced during the Albany Congress in 1754. From June 18 to July 11, representatives from seven of the thirteen British Colonies met to discuss how the colonies could defend themselves against the French during the brewing French and Indian War, the American Theater for the Seven Years’ War. Delegates discussed how to form alliances with Native Americans and how to create collaborative defense measures to protect the colonies. None of the delegates wanted to create a new nation, but several did want to create a colonial representative that could communicate with the King. The “Plan of the Union,” submitted by Benjamin Franklin, was aimed to create an executive, a President-General, appointed by the King who could represent the colonies in Native American affairs, help lead military preparedness across the colonies, and standardize inter-colony trade and financial deals. Many delegates opposed the plan because they feared they could lose colonel power with a King appointed officer controlling the colonies. Because of these concerns, the plan was heavily edited and modified before it was submitted to the British Board of Trade. Regardless of the editing, the plan was denied and forgotten. The Albany Congress set the seeds of inter-colony collaboration. While the “Plan of the Union” wasn’t popular, nor successful, this plan opened up discussions on how the colonies should operate and how to create a governmental body for the Thirteen Colonies.

Eleven years later, from October 7 -25, 1765, delegates from the Colonies met again to form the Stamp Act Congress. The conclusion of the French and Indian War harkened the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Because of the extensive military engagement waged on multiple continents throughout the war, Great Britain was running low on reserves to pay military debts. In response, Britain imposed a tax on all paper goods sent to the Thirteen Colonies. This tax funded the British soldiers that were stationed in North America to maintain peace between the colonist, the French, and the Native Americans. The Stamp Act, named for the stamp affixed to the goods that had paid the tax, was wildly unpopular with the Thirteen Colonies. The colonists believed they had already paid their “fair share” of the military debt and that Great Britain was trying to extort more money out of them. In addition, many colonies felt like they weren’t represented in Parliament because none of the members of Parliament were from the colonies or had colonial interests in mind. They argued that this representative omission violated their rights as Englishmen and that there should be “No Taxation Without Representation.” The Stamp Act Congress issued a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances against Great Britain” to protest the tax and demand representation. Outside Congress, the public began boycotting paper goods while new political groups, like the Sons of Liberty, began pressuring stamp tax distributors to stop enforcing this new tax. With these protests and boycotts, British merchants began losing revenue and protesting the Act as well. The Act was repealed on March 18, 1766. The Stamp Act Congress, while short-lived, laid the foundation for subsequent resistance to British taxation and control.

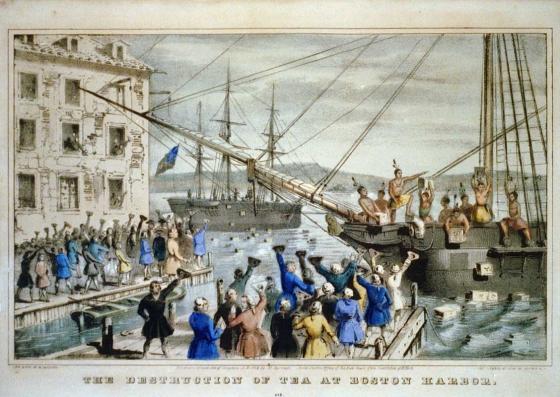

The next time these delegates met was for the First Continental Congress. After the Stamp Act was repealed, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act of 1766. This Act established that Parliament had full authority over the American Colonies and that they could pass any laws that they deemed fit to pass without American consent. American Colonists were outraged and called for its repeal to no avail. When the Tea Act was passed in 1773 to encourage and tax colonists on British East Indian Company tea, the colonists were outraged. In response, the Sons of Liberty threw an entire shipment of tea into Boston Harbor during the, now memorialized Boston Tea Party. In response, Great Britain passed the Coercive Acts to punish Boston and Massachusetts as a whole for the financial damage and the political protest. These Acts, known as the Intolerable Act to the American colonists incited the First Continental Congress to meet from September 5 to October 26, 1774. In this Congress, they passed the Continental Association to boycott all British goods in solidarity with Massachusetts. Congress assigned each state to assembly committees to ensure local compliance to the boycott and regulate prices of local goods to ensure that consumers could buy local goods. If the Acts were not repealed within the year, Congress threatened to cease all exports of American goods to Britain. In anticipation of this next meeting, Congress invited other North American colonies to join, which the colony of Georgia did. Less than a year later, the Continental Congress met again.

On May 10, 1775, eight months later, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This meeting timeline was advanced because of the hostilities between the colonists and British soldiers on April 19, 1775, during the Battle of Lexington and Concord. This Congress, unlike their predecessors, were preparing for war: they began rallying troops, creating military strategies, and writing treatises. As a last effort for peace, the Congress wrote the Olive Branch Petition to impose for a peaceful resolution between the Crown and the Colonies. King George II refused to read the petition. This petition was followed with the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms to explain why the Thirteen Colonies were to take up arms against Great Britain.

For the next eight years, the Second Continental Congress was the de facto national government. On July 4, 1776, this Congress ratified the United States Declaration of Independence that listed the Thirteen Colonies’ grievances with Great Britain and declared themselves independent. During the same time the Declaration of Independence was drafted, Congress began drafting pragmatic guidelines on how to run the governing body of the newly formed United States. This effort resulted in the Articles of Confederation. When these Articles were ratified on March 1, 1781, the Continental Congress was officially renamed the Congress of the Confederation. However, colloquially Congress was still referred to as the Continental Congress. It was not until the Constitution of the United States was made effective on March 4, 1789, that congress morphed into the United States Congress, the name of the governmental body still in existence today.

Further Reading

- Our Lives, Our Fortunes and Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776 By: Richard Beeman

- The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution By: David O. Stewart

- American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 By: Alan Taylor