Defiance in the Valley

By Jonathan A. Noyalas, for Hallowed Ground, Spring 2012

On the evening of March 11, 1862, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson gathered his subordinates for a meeting at his headquarters in Winchester, Va. Over the course of the previous several days, a sizable Union army — approximately 35,000 strong — commanded by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks had moved closer to Winchester’s outskirts. Although Jackson only had approximately 3,500 men in his command, he determined to not let Winchester go without a fight. Despite Jackson’s desire to launch a surprise night attack on Banks, his brigade commanders prudently urged their chieftain to withdraw and live to fight another day.

While pragmatism prevailed, the decision to withdraw bothered Jackson tremendously. Rev. Robert Graham, a man with whom Jackson established a friendship during his time in Winchester, noted that not only did giving up Winchester without a fight dismay Jackson, but the idea of leaving Winchester’s overwhelming Confederate population to Banks’s rule greatly disheartened Stonewall.

As Jackson’s army marched south on the night of March 11, the mood of Winchester’s Confederate civilians soured. The following day it worsened as Banks entered the town triumphantly and accepted its surrender. Resident and staunch Confederate Mary Greenhow Lee confided pessimistically to her diary: “All is over and we are prisoners in our own houses.”

At the time Banks neared Winchester, President Abraham Lincoln began to seriously doubt that his general-in-chief George B. McClellan could handle the duties of that job while simultaneously directing the Army of the Potomac in its campaign to take Richmond via the Virginia Peninsula. After Lincoln confined McClellan’s responsibilities to the Army of the Potomac, the president urged McClellan to make certain that he leave behind ample forces to leave Washington, D.C., “entirely secure.” Consequently, McClellan ordered Banks to send Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick’s division from the Valley to Manassas to protect Washington, D.C. By March 16, McClellan called for Banks to send all of his remaining force out of the Valley, except for one brigade, which would oversee the rebuilding of the strategically vital Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

McClellan’s directive bothered Banks. At the time Banks did not know Jackson’s precise location, overall strength, ability to be reinforced or his ultimate strategic objectives. With so much uncertainty, Banks ordered Brig. Gen. James Shields to lead a reconnaissance mission toward Strasburg. Shields led his division south on March 18, and, although he engaged with Confederate cavalry commanded by Col. Turner Ashby south of Middletown, he concluded that Jackson posed no major threat. Armed with this knowledge, Banks acceded to McClellan’s request and ordered Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’s division out of the Valley to protect the capital.

While the bulk of Banks’s army marched out of the Valley, the anxiety of Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston increased as he withdrew his command from Manassas to Richmond. Fearful that Banks’s troops would support McClellan’s operations against the Confederate capital, Johnston sent a note to Jackson that urged him to do all he could to prevent any more Union forces from leaving the Valley. “It is important to keep that army in the valley,” Johnston penned Jackson, “and that it should not reinforce McClellan.” With that directive, Jackson’s role in the Shenandoah Valley had been defined: utilize the region as a diversionary theater of war in order to protect Richmond and, consequently, the hopes of the militarily beleaguered Confederacy.

First Blood at Kernstown

As a cold wind whipped through the Shenandoah Valley on the morning of March 22, Stonewall Jackson’s army, approximately 3,500 infantry-men strong, marched north from their camps around Mount Jackson, while Ashby’s cavalry hastened toward Winchester. When the troopers entered Newtown (present-day Stephens City), a young boy informed them that all of the Union forces had evacuated Winchester, information Ashby’s horsemen soon learned was not entirely accurate. As the Confederate cavaliers neared Winchester’s southern outskirts, they encountered pickets from Shields’s division — the only remaining portion of Banks’s command. As the report of small arms fire erupted, the area’s Confederates beamed with expectations of Southern success. A veteran of the 29th Ohio noted: “The citizens… were in high glee at the prospect of being rid of those odious Lincoln hirelings.” Although a Confederate artillery fragment from Capt. R. Preston Chew’s Battery fractured Shields’s left arm, Ashby’s command could not break the line.

Despite defeat, Ashby believed his operation garnered important information about Union troop strength in the area. Several citizens communicated to Ashby that Shields had made preparations for a complete withdrawal and that only a few regiments remained. Ashby sent several scouts into Winchester after the skirmish who confirmed the information.

Ashby quickly relayed the intelligence, which later proved grossly flawed, to Jackson. With word of a Union withdrawal to the east and Johnston’s directive ringing in his ear, Jackson knew he needed to strike the following day. Regardless of the military necessity, Jackson grappled with a personal issue in determining when to launch his offensive. If Jackson struck on March 23, it meant he would have to fight on a Sunday. The deeply religious Jackson penned his wife, Mary Anna, that he “was greatly concerned” by the decision to order his men into battle on the Sabbath, but “important considerations… rendered it necessary to attack.”

As Jackson determined to push north, the Union command structure changed. With Shields wounded, battlefield command turned over to Col. Nathan Kimball. A physician prior to the war, as well as a veteran of the Mexican-American War, Kimball had a reputation as a “stout old fighter.” Although wounded and unable to command troops in battle, Gen. Shields advised Kimball to move two of the division’s three brigades south to Kernstown in an effort to secure all of the possible approaches that Jackson could take to get to Winchester.

On the morning of March 23, while Jackson marched the main Confederate body north on the Valley Pike, a force including cavalry, three cannon and four infantry companies advanced against Kimball at Kernstown. Sixteen Union cannon posted atop the commanding heights of Pritchard’s Hill drove off Ashby’s command by about 11:00 a.m. When Jackson arrived on the battlefield, he surveyed the situation and easily discerned that the key to winning the battle would be silencing the Union artillery. Jackson ultimately concluded that if troops and artillery could be placed on a piece of high ground west of Pritchard’s Hill — Sandy Ridge — he could annihilate the Federals.

Unfortunately for Jackson, Kimball rushed troops to Sandy Ridge and blocked his plans. Although the Confederate brigades of Col. Samuel Fulkerson and Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett fought tenaciously on Sandy Ridge, the pressure from Kimball’s brigades, waning ammunition supplies and lack of communication between Jackson and his subordinates compelled a Confederate withdrawal. That night Jackson halted his army several miles south of the battlefield in Newtown.

Mysterious Confederate Menace

Although Jackson’s loss became another in a string of Confederate defeats in the early months of 1862, the battle — or at least how it was reported to war-planners in Washington, D.C. — aided Jackson’s mission of strategic diversion in the Valley. Although not present on the battlefield during the fight, Shields quickly informed his superiors that his division of approximately 8,000 men had defeated an enemy numbering at least 11,000 — four times Jackson’s actual strength. Banks believed the grossly exaggerated report and immediately directed Gen. Williams’s division back to the Valley, with additional troops to follow. In total, the War Department redirected about 20,000 Union soldiers — who could otherwise have been used to support McClellan’s operations on the Virginia Peninsula — to deal with Jackson. “The battle of Kernstown,” recalled a member of Jackson’s command after the war, “if not to be claimed as a victory for the Confederates served all the purposes of one.”

In the days after the battle, Jackson pulled his army back to the area of Rude’s Hill, a defensive position several miles south of Mount Jackson, where his ranks began to swell — growing to about 6,000 men by mid-April. Meanwhile, Banks, with about 20,000 men, marched south in pursuit, causing Jackson to withdraw south to Conrad’s Store. From here Jackson knew he could maintain a strong defense, control Swift Run Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains and have the capacity to launch attacks against Banks’s command. Banks, however, mistakenly interpreted the movement as a Confederate withdrawal.

At Conrad’s Store, the Southern force grew further with the addition of Brig. Gen. Edward “Alleghany” Johnson’s Army of the Northwest — a small command of about 3,500 men. Moreover, Gen. Robert E. Lee, then military adviser to Confederate president Jefferson Davis, informed Jackson that he would also receive support from Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell’s division.

Although Lee wanted Jackson to use Ewell’s support and go after Banks, another issue concerned Jackson — the presence of 20,000 Union soldiers commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont west of the Shenandoah Valley. Since early April, the vanguard of Fremont’s army under Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy had been inching its way closer to the Valley, ultimately intending to disrupt the important rail center at Staunton. Jackson knew that if Milroy succeeded, the Confederate lifeline with Richmond would be severed; he had to silence Milroy before moving on Banks.

First Blushes of Triumph

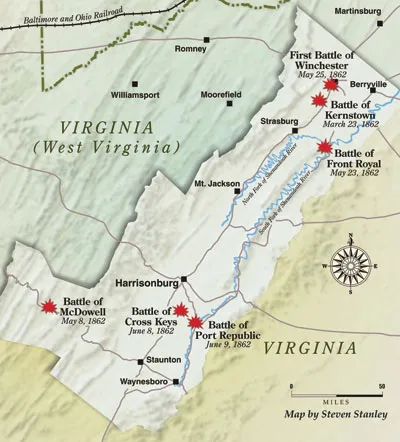

Jackson began his movement on April 30, when he marched his men east. Although this movement presented the appearance of a withdrawal from the Valley, Jackson marched his men to Mechum’s River Station, boarded the train cars of the Virginia Central Railroad and steamed west toward Staunton, arriving on May 4. From there the men marched west and, on May 8, engaged and defeated the brigades of Milroy and Brig. Gen. Robert Schenck at McDowell. Despite the smallness of the engagement, Jackson’s success buoyed the spirits of the beleaguered Confederacy. One of Jackson’s staff officers noted: “This announcement was received… with delight… because it was the first blush of the returning day of triumphs.”

With the immediate threat from Fremont eliminated, Jackson returned to the Valley and focused his attention on Banks. After linking up with Ewell’s division near Luray on May 21, Jackson’s army, now swollen to 17,000, marched north through the Luray Valley to strike Banks’s strategic left flank at Front Royal, an important depot along the Manassas Gap Railroad, which was the Union force’s supply lifeline.

By mid-May, Banks’s army — again reduced considerably by the War Department’s redirection of troops from the Valley to support McClellan — consisted of less than 10,000 men. His defensive line stretched from Strasburg east to Front Royal, a distance of slightly more than 10 miles. At Front Royal, a place he deemed an “indefensible position,” Banks placed a command of approximately 1,000 men under Col. John R. Kenly.

On May 23, Kenly’s command was the first portion of Banks’s army to feel Jackson’s wrath. When Kenly learned of the approaching Confederates, he knew he stood no chance of defeating Jackson, but hoped that he might be able to delay the Southerners long enough to get Union stores out of Front Royal. More important, Kenly hoped to prevent Jackson from moving west and cutting off Banks’s northern retreat route to Winchester. Throughout the afternoon of May 23, Kenly’s small command did all it could to delay Jackson, but the effort halted several miles north of Front Royal at the small crossroads of Cedarville. There Col. Thomas S. Flournoy’s 6th Virginia Cavalry crushed the Federals. Kenly — twice wounded during the fight — and approximately 900 of his men fell captive to the Confederates.

Glorious Success at Winchester

With Front Royal secure, Jackson turned his attention to the west and moved toward the Valley Pike the following day to cut off Banks’s retreat path to Winchester. But aside from a small melee in Middletown, during which Jackson struck the rear of Banks’s column, the Federal soldiers successfully withdrew to Winchester and established a defensive line south of town. Banks placed Abram’s Creek between his army and the Confederates and anchored both of his flanks on high ground. Despite the advantage of terrain, expectations among Banks and his officer corps remained low. Still, they knew they had to fight to buy enough time for the Union wagon trains to get safely across the Potomac.

Jackson launched his assault around 5:40 a.m. on May 25, when Ewell’s division struck first against Col. Dudley Donnelly’s brigade positioned atop Camp Hill. Unable to break Donnelly’s line, Jackson focused on Banks’s right atop Bower’s Hill, turning to the shock troops of his army, Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor’s Louisiana Brigade. Taylor led a successful flank attack against the Union right and easily rolled up Banks’s line. Unable to resist superior numbers, the Union army retreated north to Williamsport, Md.

As the news of Jackson’s victories at Front Royal and Winchester reached Richmond, the Confederate capital erupted in jubilation, with the Richmond Examiner recording that “Richmond yesterday experienced a decided and wholesome feeling of elation and rejoicing… of the glorious successes of Jackson.”

Not only did Jackson’s victory at Winchester bolster spirits in Richmond, but it arguably emerged as the pivotal point in the campaign — the moment when people in both North and South began to truly notice Stonewall Jackson. Northern journalist George Alfred Townsend penned: “Jackson’s glory has steadily increased. He was first brought into notice at Winchester.” Furthermore, if one trusts the validity of artwork as a tool of historical interpretation, as did 19th-century English intellectual John Ruskin, the claim is further solidified. When artists William D. Washington and Louis M.D. Guillaume received separate commissions to produce works of art in the immediate aftermath of Jackson’s death, both chose scenes from his victory at Winchester as the backdrop.

Like a Wind from the Mountains

While the Confederacy praised Jackson, war-planners in Washington, D.C., looked for a way to counter his efforts. With Banks defeated, the Lincoln administration turned to generals Fremont and Shields to trap Jackson between their converging forces. Unfortunately for the Federals, Jackson discovered the plan and slipped south of Strasburg before the two Union forces could unite. The two Federal commanders had no choice but to pursue him; Fremont followed Jackson south through the main Shenandoah Valley, while Shields paralleled the chase east of Massanutten Mountain in the Luray Valley. A key element of Jackson’s plan was using the Valley’s geography to his advantage — so long as he could keep the Massanutten between Fremont and Shields, Jackson believed he could win. As Jackson marched south, he knew that for Shields and Fremont to join forces, they would have to cross the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. With all of the bridges over the river destroyed, the likely candidate for unification was the junction of the North River and South Fork at Port Republic.

As Jackson marched his army toward Port Republic, Fremont pursued and, on June 6, engaged the rear of Jackson’s column at Harrisonburg. Although a Confederate victory, it cost Jackson the loss of his cavalry chief, Col. Turner Ashby. Two days later, a portion of Jackson’s army commanded by Ewell clashed with and defeated Fremont’s army at the small hamlet of Cross Keys — situated between Harrisonburg and Port Republic. The next day, troops from Shields’s division commanded by Brig. Gen. Erastus Tyler braced for the final battle of the Valley Campaign at Port Republic. Although the Union artillery held a commanding piece of high ground known as the Coaling, repeated infantry assaults against the position forced a Federal withdrawal and cemented Confederate fortunes in the Valley.

After the twin Confederate victories, Jackson moved his army to Brown’s Gap — a point in the Blue Ridge that allowed him the flexibility to deal with a potential advance by Fremont or Shields. When neither Federal commander threatened, Jackson moved his army back into the Valley and to Weyers Cave, where he hoped to await reinforcements to continue his successes. Despite the strategic dividends of Jackson’s campaign in the Valley, Gen. Lee, the Army of Northern Virginia’s new commander, needed his services east of the Blue Ridge to protect Richmond and, on June 18, Jackson’s army marched east.

This Stonewall … He Fights to Win

As Stonewall’s command crossed the Blue Ridge that day, his campaign in the Valley and, in the estimation of one observer, “a chapter in history which is without parallel,” came to a close. At the time, no one in the Confederacy held a more iconic reputation than Jackson. That spring, his men had marched nearly 700 miles, won five battles and inspired an infant nation. News of his victories infused fresh life into the languid pulses of the Confederacy. “This campaign made the fame of Jackson as a commander…. The rumor of his rapid movements and constant successes came like a wind from the mountains to the Confederate capital,” wrote John Esten Cooke after the war.

Confederate soldiers in other theaters of war looked for ways to connect with Jackson, while the civilian population adored him. Famed wartime diarist Mary Chestnut believed that Jackson’s victories would not only help the war effort, but also might catapult Jackson to ultimate leadership of the Confederacy. “This Stonewall… He fights to win—God bless him and he wins,” Chestnut mused. “He will be our leader… after all.”

Although Jackson added to his military prowess over the next 11 months of his life, and, perhaps, saved his greatest act for Chancellorsville, his operations in the Shenandoah Valley offered the only time his full generalship could be put on display — a career still studied and admired today. Perhaps Jackson’s wife Mary Anna, in her Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson, best captured how Jackson’s victories, against the backdrop of Confederate defeat elsewhere, catapulted him into the pantheon of military legends. “Brilliant as were the achievements of General Jackson during the succeeding months of his too brief career,” she chronicled, “it was his Valley Campaign which lifted him into great fame; nor do any of his subsequent achievements show more striking the characteristics of his genius.”

Learn More: Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign