The tumultuous political and military position occupied by the Commonwealth of Kentucky during the Civil War era can be encapsulated in a single, deceptively simple fact: Five men can claim to have held the title of governor between 1861 and 1865.

The Civil War Governor of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, a project of the Kentucky Historical Society, has digitized, transcribed and annotated more than 10,000 documents, tagging the people, places and entities referenced therein to illustrate relationships within the Bluegrass State during the conflict. Although the project’s editorial focus is on the office of the governor, it is designed to uncover the voices of everyday Kentuckians struggling to cope with unprecedented societal chaos. These people reached out to their government in letters, court cases and other official documents, leaving a tangible imprint on the written historical record. Via its web of hundreds of thousands of networked nodes, the project shows scholars new patterns and hidden relationships, and recognizes the humanity and agency of historically marginalized people.

“I have developed a profound empathy for both the plaintive citizens bringing horrifying tales of death, crime, sexual violence, destitution and starvation, as well as for the representatives of government at all levels who are chronically unable to muster sufficient resources to address the systemic problems they saw,” said program director Patrick Lewis. “It is easy to see the Civil War as a crisis of elected government — at a legislative, gubernatorial, Congressional, and especially Presidential level — but I have come to appreciate the war as it drug down an underprepared and underpowered civil service under the weight of modern, total war.”

The desire to craft a cross-referenced and searchable digital clearinghouse of information grew out of the Lincoln Bicentennial and Civil War Sesquicentennial, and the project is intended as a lasting contribution to the academic record from those commemorations. Full-time editorial work, funded thanks to the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the National Endowment for the Humanities, began in 2012. The robust and dynamic website launched in 2016, and continues to grow as new documents are added and linked, allowing deeper levels of connection and understanding to emerge.

The project has proven a treasure trove for researchers, whether traditional academics or amateur genealogists. It has also become a rich resource for students and classroom educators, providing a massive selection of primary source documents representing a diverse range of attitudes and experiences in a user-friendly format.

“History has too few characters. We don’t know enough names. We don’t know enough stories. This limits what we can say about the past,” said Lewis. “The Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition proposes a bold new solution to this problem. We find the characters, hidden in archives across the country. We publish their stories in the form of 30–40,000 historical documents. And we treat every individual — man or woman, free or slave, Union and Confederate — as an historical actor worthy of study.…This is the closest thing we can get to a time machine.”

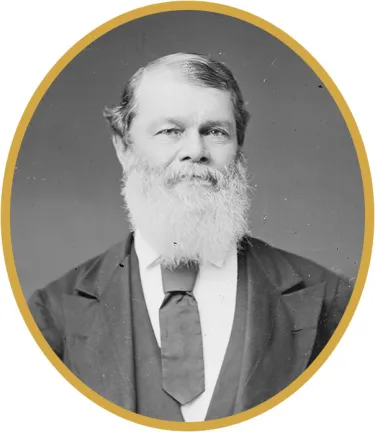

Holding the executive office during the contentious presidential election of 1860, Beriah Magoffin was not a supporter of Abraham Lincoln and embodied the state’s pro-slavery, anti-secession stance. After the firing on Fort Sumter, he refused the call for volunteers to put down the rebellion, and the state militia refused entrance to military personnel from either side. In August 1861, Unionists seized the legislature and began gradually stripping away Magoffin’s executive powers. During the Confederate invasion in the summer of 1862, he was pressured to resign.

The hand-chosen successor to Magoffin, James F. Robinson occupied the executive office for a short but critical window in late 1862 and 1863. He took power as Confederate armies marched through the state, forcing him to flee to Louisville and allowing Confederate provisional governor Richard Hawes to be inaugurated at Frankfort. The loss of private property to a Southern army increased Kentucky’s Unionist zeal, but the Emancipation Proclamation shook its slaveholding society, leaving Robinson to walk a tightrope.

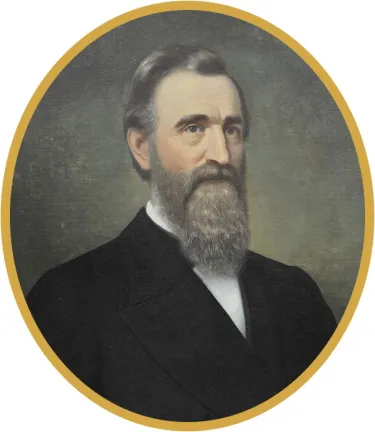

Thomas E. Bramlette was elected governor in 1863, as military action in the west shifted out of Kentucky and toward Atlanta. Like his predecessor, he sought to be a moderate voice in the divided state, opposing the rebellion and urging citizens to regard slavery as a dying institution that they must lay the groundwork to survive without. Opposing the extension of rights to freed African Americans, Bramlette came into conflict with Washington over recruitment of USCT units. Despite the lack of formalized military campaigns during his tenure, Bramlette had to contend with guerrilla conflict that transitioned into racially motivated violence after the war ended.

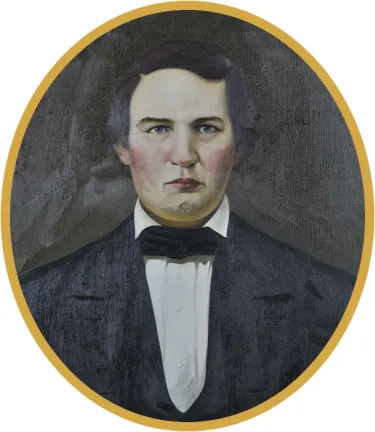

As head of a Confederate government in exile, George W. Johnson did little actual governing. Wealthy and well-connected, he had been a leading pro-secession voice who was forced to flee the state following Kentucky’s September 1861 declaration of allegiance to the Union. The next month, those exiles met in Russellville, which was occupied by a Southern army, to form their own government and gain admittance to the Confederacy. Forced to flee alongside the army with the loss of Forts Henry and Donelson, he volunteered as an aide to his cousin, Confederate general and former U.S. vice president John Breckinridge, until he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Shiloh. He died in a Union camp.

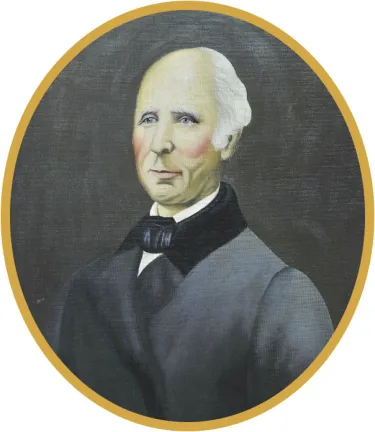

Like Johnson, Richard Hawes had fled Kentucky when the government declared its allegiance to the Union. He returned to help administer the government, but illness prevented him from taking an immediately active part. As such, Hawes did not hold a seat on the 10-member council that directly assisted Johnson, but this fact is what made him eligible to be named provisional governor upon the latter’s death. During the Confederate Heartland Offensive in the summer of 1862, Hawes was formally sworn in at Frankfort, but the ceremony was interrupted by Union artillery, which presaged the Battle of Perryville, fought only days later. Too weak to remain in Kentucky, the Southern army retreated, Hawes with it.

This article appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of Hallowed Ground magazine. Painting courtesy of Kentucky Historical Society Collections. Beriah Magoffin photograph courtesy Library of Congress.