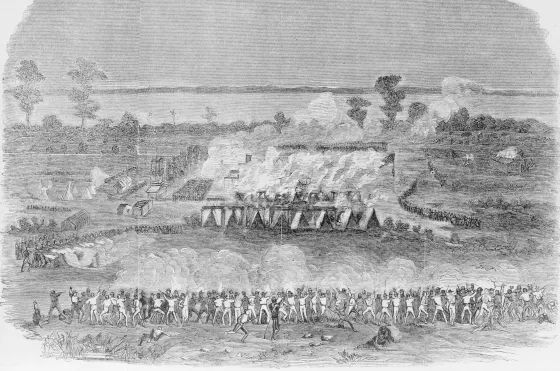

"Attack of the Seminoles on the Block House" by T.F. Gray and James, 1837.

After the United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821, solidifying its existing defenses and constructing new fortifications was crucial to defending the vast tropical territory and, by extension, the country itself, from European imperial powers in the Western Hemisphere. U.S. Navy officers immediately sought locations for naval depots and forts. Naval stations at Key West and Pensacola were established in the 1820s. Officers determined that, in addition to securing the Florida Straits – one of the world’s busiest shipping routes – Key West and the Dry Tortugas could provide secure anchorage for ships during storms or in wartime, and that Pensacola could protect commerce from Gulf ports like Mobile and New Orleans, among others. U.S. Army engineers began constructing masonry fortifications, and reinforcing existing forts, like the Castillo de San Marcos, as part of the Third System of Defense (1817-1870).

Before the U.S. Army engineers constructed permanent masonry fortifications, U.S. soldiers and American civilians in Florida established and settled around impermanent forts. Conquering Florida’s territory involved waging war on Florida’s Native American population in the Seminole Wars, which inspired the establishment of several forts that later became settlements. As a result of the first two Seminole Wars (1817-1818 and 1835-1842), more than eighty blockhouses, camps, forts, and stockades were established from Apalachicola across the peninsula. These were earthen, impermanent forts designed to provide troops with temporary protection. Many of these settlements survive today. They include: Forts Basinger, Lauderdale, Meade, Myers, Pierce, Walton, and White. Other settlements that removed “Fort” from their names include: Dade City, Denaud, Jupiter, and Maitland. And some settlements adopted new names: Tampa (Fort Brooke), Bartow (Fort Blount), Clearwater (Fort Harrison), and Miami (Fort Dallas).

The Second Seminole War (1835-1842), the bloodiest of the wars with the Seminoles, began on December 28, 1835, when an Indian killed an Indian agent and a lieutenant at Fort King near Ocala. This seven-year guerilla war in which the Seminoles fought Americans to retain their land in north-central Florida forced American troops to seek security as they combatted Native Americans throughout Middle Florida. During this war, the War Department ordered Lieutenant-Colonel George Mercer Brook from Pensacola to Tampa to establish a fort, which began as a cantonment, where the Hillsborough River empties into Hillsborough Bay. The site became known as a fort in 1835. After the Second Seminole War, the U.S. government encouraged settlement in the region through the Armed Occupation Act of 1842, which offered 160 acres to any white head of family, or single man over 18, who was able to bear arms, harvest at least five acres, and live on the land for five consecutive years. These pioneers could aid U.S. soldiers at policing the new boundaries of the Seminoles’ reservation, to which the tribe objected.

Tensions precipitated into the Billy Bowlegs War in 1856, during which General Daniel E. Twiggs ordered the establishment of several forts that spanned the width of the Florida Peninsula from Fort Brooke to Fort Capron (near present-day Fort Pierce). Among these were Forts Alfia, Meade, Arbuckle, Drum, Vinton, and Clinch (at Frostproof. Other forts with the same name existed at Fernandina, on the Withlacoochie River, and at Pensacola).

Coastal defenses to protect Florida’s vast coastline either predated or were constructed concurrently, with the interior defenses that were designed to guard against and forcibly remove the Seminoles. Throughout U.S. history, the Army Corps of Engineers built coastal forts in three Systems of Defense to minimize the necessity of a large standing army and to deter invasion. Florida’s forts were constructed, and Fort Marion was improved, as part of the Third System of Defense. By the 19th century, the Castillo de San Marcos, built by the Spanish, already existed. Construction on the Castillo began in 1672 and was completed by 1695. The fort was made of coquina, durable shell stones brought from nearby Anastasia Island, that can resist cannon fire. When the U.S. acquired Florida in 1821, the Castillo de San Marcos was renamed Fort Marion. It served as a military prison during the Second Seminole War, the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War.

The acquisition of Florida from Spain gave the U.S. both the opportunity and the obligation, for the sake of national commerce, to fortify Florida’s vast coastline. After the War of 1812, Forts Barrancas, McRee, Pickens, Jefferson, and Taylor were constructed on Florida’s Gulf coast, while Fort Clinch (Amelia Island), was situated on the Atlantic coast. Once work began, engineers and laborers, free and enslaved, confronted the challenges of engaging in construction at remote locations in a tropical climate including heat, hurricanes, delayed supply shipments, and diseases like typhoid and yellow fever, which created or exacerbated labor and material shortages.

Forts Barrancas, McRee, Pickens, Clinch (Amelia Island), Jefferson, and Taylor were constructed as part of the Third System of Defense to safeguard American commerce and, in the case of Forts Taylor and Jefferson, protect the Florida straits. The Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean were key to both U.S. domestic and foreign trade. Southerners on the Gulf coast transported goods and crops for trade, including “King” Cotton, to the Gulf of Mexico where they were loaded on ships that sailed past Pensacola, down to the Dry Tortugas and Key West, through the Florida Straits, and to the open waters of the Atlantic. Pensacola’s forts – Barrancas, McRee, and Pickens – were critical to guarding not only steamships loaded with goods, but also the town’s strategic port. Fort Clinch, on the northern tip of Amelia Island, dated to colonial times, but formal construction on the masonry fortification began in 1847. It was designed to protect the St. Mary’s River which connected to the Cumberland Sound and the Port of Fernandina. Fort Taylor at Key West and Fort Jefferson on Garden Key in the Dry Tortugas guarded the precarious Florida Straits, which were historically known for shipwrecks. All forts, but especially Forts Taylor, Jefferson, and Pickens served as physical representations of U.S. strength to European imperial powers that held possessions, or aimed to meddle, in the Western Hemisphere.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began work on Fort Barrancas, and the Advanced Redoubt, in 1829 to protect the Pensacola Navy Yard. These defenses were located on the mainland, on the site of the old Spanish defenses of Pensacola Bay, and were built largely by slaves for whom the army contracted with local slaveholders who received payment for their chattels’ labor. Chief Engineer Joseph G. Totten designed the fort and Captain William H. Chase served as the fort’s on-site engineer. Chase supervised the fort’s sporadic construction that stalled with the Civil War’s outbreak. Work on the fort ended in 1870.

The masonry fort was designed to mount thirty-three barbette guns and eight flanking howitzers but, in 1861, Fort Barrancas’s armament totaled approximately ten guns, most of which U.S. garrison troops had moved into Fort Pickens or spiked by the time Confederate soldiers took the fort. The U.S. garrison fired shots, thought to be blanks, at Florida militia troops who ran to the drawbridge in an attempt to take the fort. After this incident, U.S. Lieutenant Adam Slemmer, commanding at Pensacola, ordered 20,000 pounds of gunpowder destroyed and marched U.S. troops from Barrancas to Fort Pickens while Florida state troops occupied Barrancas, the Advanced Redoubt, and Fort McRee. On November 22 and 23, 1861, and again on January 1, 1862, U.S. troops from Fort Pickens barraged Barrancas’s Confederate defenders but caused little damage. Federal troops took over Fort Barrancas in May 1862 when Confederate soldiers evacuated Pensacola. It remained in Union hands for the remainder of the war.

Engineers and slave laborers constructed the Advanced Redoubt between 1845 and 1870 as part of the Pensacola Navy Yard’s defenses. It was situated nearest the Navy Yard on the peninsula, while Forts Barrancas, McRee, and Pickens guarded the harbor’s entrance. On October 8, 1863, Confederate troops tried to dislodge U.S. defenders, including soldiers from the United States Colored Troops, but the U.S. soldiers suffered no casualties and forced Confederates to retreat.

Construction on Fort McRee (often misspelled McRae) began in 1834 on Foster’s Bank (Perdido Key) at the entrance to Pensacola Harbor and was completed in 1839. After Florida’s secession in January 1861, U.S. troops from Fort McRee moved into Fort Pickens and Confederate troops soon occupied McRee, though it was not permanently garrisoned. The U.S. bombardment from Fort Pickens on November 22, 1861, caused significant damage to Fort McRee as the U.S.S. Niagra and the U.S.S. Richmond contributed to the attack. Confederate troops abandoned Fort McRee in May 1862 when they evacuated Pensacola.

Like Fort Barrancas, construction on Fort Pickens began in 1829 and, by 1834, the fort was complete. Lt. Col Totten originally designed the fort, which occupies the western end of Santa Rosa Island, while Brigadier General Simon Bernard modified the defensive scheme for Pickens, to facilitate faster construction of Fort McRee – a decision that underscored the importance of the Navy Yard. Together, these forts guarded the harbor, while Barrancas protected mainland approaches to Pensacola and comprised the overall U.S. plan to have four forts guard Pensacola Bay. Spain and Britain previously constructed fortifications on the mainland to guard the bay, but the U.S. plan called for two forts on the mainland and two on islands at the bay’s entrance. Captain William H. Chase supervised the construction of Fort Pickens and a labor force that included skilled laborers, both free and enslaved. Eighty U.S. troops and Lt. Slemmer occupied Fort Pickens after Florida seceded on January 10, 1861. Prior to this, no troops had occupied Fort Pickens since 1848.

Confederate troops made several unsuccessful attempts to capture the fort. The first demand for surrender was ironically led by Col. Chase who resigned his U.S. Army commission and joined the Confederacy. On October 9, 1861, Confederate troops under General Braxton Bragg, in a surprise attack, attempted to take Fort Pickens during the Battle of Santa Rosa Island. Confederate troops ultimately abandoned Pensacola in May 1862. Union troops held the fort for the rest of the Civil War and it doubled as a military prison towards the war’s end. After the Civil War, the U.S. government ratcheted up its program of Indian removal and, from 1866-1868, U.S. authorities detained fifty Apache men, women, and children, including Geronimo and Cochise’s son Naiche, in the officers’ quarters where the prisoners attracted much public attention.

Plans for Fort Taylor unfolded in 1844 and U.S. Army engineers began construction in mid-1845 to safeguard Key West’s natural deep-water harbor. Fort Taylor was constructed on a hard rock shoal 440 yards from the island’s southwest corner which afforded protection of all approaches to the port of Key West. In 1850, the fort was named for General Zachary Taylor who died in July 1850 while serving as President. Engineers and laborers – from skilled Irish and German craftsmen to slaves rented from Key West’s slaveholders – built the fort with bricks shipped mostly from Pensacola. They had made progress on the fort when, in October 1846, a hurricane created a significant setback as it swept away caissons and damaged the fort’s structure. The project recovered, albeit slowly given problems with regular shipments of supplies, and by April 1855 Fort Taylor’s first tier of casemates was finished and artillery mounted.

Fort Taylor remained unfinished when Florida seceded from the Union on January 10, 1861. After news of Florida’s secession reached Key West, Captain John M. Brannan of the 1st Artillery, stationed at Key West barracks, marched his forty-four men across the island and into Fort Taylor to secure it and Key West for the Union. During the war, army engineers, garrison soldiers, northern laborers, and blacks, both free and slave, made improvements to Fort Taylor by fortifying its land side to prevent attack from either the Confederacy or from imperial powers in the Caribbean, and by installing tidal-flush toilets and a desalination plant for water. Neither Confederate troops nor European powers attempted to take Fort Taylor, however. Throughout the war, the U.S. garrison at Key West imprisoned Confederate blockade runners, civilians suspected of disloyalty (mostly from Key West), and Union soldiers – from the island’s garrison and on the mainland – who violated the articles of war.

During the war, U.S. Army engineers and the laborers who fortified and improved Fort Taylor and built military roads across the island also constructed two Martello Towers at Key West to secure Fort Taylor’s land side and deter an amphibious landing. Plans for these towers originated in the antebellum period and were modeled on towers constructed during the Napoleonic Wars, but the projects were not initiated until late 1861 when the U.S. government began procuring the land for each tower from their owners. One Martello Tower was constructed on Key West’s extreme northeast end, and the other approximately two miles closer to the town center. The towers eventually became known as the East and West Martello Towers, which changed from Fort Taylor Tower Number One and Advanced Battery and Fort Taylor Tower Number Two and Advanced Battery. Although rifled cannon signaled that masonry construction was becoming obsolete with the Union bombardment of Fort Pulaski (Georgia) on April 10-11, 1862, the Martello Towers, like Fort Taylor, were constructed with brick. By 1864, the railroad connected each of the towers to Fort Taylor. Like Fort Taylor, the Martello Towers were never engaged in combat during the Civil War, despite fears among Key West’s garrison troops and officers that Confederate troops, England, or France might strike the island.

Fort Jefferson on Garden Key in the Dry Tortugas also never witnessed combat but communicated U.S. military strength to imperial powers in the Western Hemisphere. In 1829, naval Lieutenant Josiah Tattnall surveyed the Tortugas and determined that any nation that occupied the islands would control navigation of the Gulf since the islands’ position protected U.S. commerce in the Mississippi Valley and throughout the Gulf coast. Construction of Fort Jefferson began in December 1846 under the supervision of Second Lieutenant Horatio G. Wright, was championed and designed by Brigadier General Joseph G. Totten, Chief Engineer of the U.S. Army Engineers (1838-1864), and was sketched by Lieutenant Montgomery C. Meigs. In late 1850, the War Department named the structure Fort Jefferson after Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father and the third U.S. president. The fort would be shaped as a hexagon with two tiers of casemates to mount 150 cannon, with an additional 150 mounted on top of the fort. U.S. Army engineers hired slaves from owners at Key West throughout the construction process and paid owners $20.00 per slave per month for their labor. Throughout the thirty years that work on the fort took place, enslaved laborers, northern artisans, soldiers, Union deserters, convict laborers, and army engineers toiled to complete what is now the largest brick structure in the Western Hemisphere, a distinction gained since much of Fort Pickens was destroyed. But the fort was never fully completed. U.S. Army engineers in 1864 discovered that the fort was constructed on coral boulders and sand rather than a solid coral reef as originally thought, which contributed to significant settling and consequent structural damage.

During the Civil War, Fort Jefferson was garrisoned by Union soldiers, averaging around 500 men, many of whom – like those at Key West – were disgruntled with garrison duty and yearned for the chance to prove themselves in combat. Instead, the garrison troops spent most of their time drilling, constructing quarters for themselves and their officers, and guarding prisoners, mostly Union deserters and soldiers convicted by court-martial since Fort Jefferson served as a military prison. After the war, Fort Jefferson detained four of the Lincoln conspirators implicated in the assassination plot that took his life and wounded Secretary of State William Seward: Michael O’Loughlin, Samual Arnold, Edward Spangler, and Dr. Samuel Mudd, whom President Andrew Johnson pardoned for helping to alleviate the 1867 yellow fever epidemic that plagued 270 soldiers out of the 300-man garrison and caused 38 deaths. The U.S. Army abandoned Fort Jefferson, yet incomplete, in 1874, but the fort’s lighthouse was replaced in 1877.

Today, Florida’s interior fort sites constructed during the Seminole Wars serve as a reminder of the U.S. government’s aggressive desire for land which cost many Native Americans their lives, while the state’s coastal fortifications serve as a reminder of the long-standing U.S. foreign policy of isolationism. During the early to mid-nineteenth century, Americans developed a domestic economy in the First Industrial Revolution. The U.S. government eschewed military and political treaties with European powers, but engaged in trade with European nations, exporting domestic and importing foreign goods for the benefit of the American people. Florida’s forts, and the naval stations that they protected, helped to make both domestic and international trade possible while signaling that the U.S. desired to stay out of foreign conflicts.

Further Reading:

-

A History of Florida Forts: Florida’s Lonely Outposts By: Alejandro M. De Quesada

-

Florida: A Short History Revised Edition By: Michael Gannon

-

Our Sea-Coast Defences By: Eugene Griffin