From Gettysburg to the Western Front

From 1914 to 1945 the world endured a period of suffering unlike any other in human history. World wars, civil wars, the Great Depression, the rise of Nazi Germany, the holocaust, and the Spanish flu epidemic were just some of the catastrophes that ravaged the world during this time period.

Throughout this same time frame, and largely due to the crises above, an estimated 140 million humans lost their lives around the world. While the casual observer might associate the majority of these deaths with the Holocaust and the World Wars, the reality is that roughly one-third of the 140 million deaths can be attributed to one event ̶ the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-1920.

Originating during the last year of World War I, probably on an army base at Fort Riley, Kansas, the Spanish flu was carried across the United States and the Atlantic Ocean by the growing number of American soldiers, sailors, and Marines heading off to war.

In the United States, the epidemic spread like wildfire. Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and countless cities and small towns in between were ravaged by the Spanish flu. According to author John M. Barry, the epidemic killed more people in 24 weeks than AIDS killed in 24 years and killed more people in one year than the Black Death killed in a century.

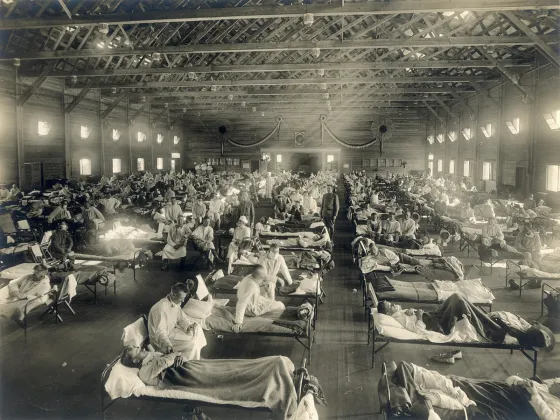

Across the Atlantic, the Entente and Central Powers had endured three years of gas attacks, the first use of the flamethrower, massive and shocking artillery bombardments, and untold battlefield horrors. Now appeared a new and deadly threat to men packed into barracks and trenches. A new front of sorts had opened. Hundreds of millions of people around the world were diagnosed with the virus, including hundreds of thousands of soldiers serving on each side.

With strict wartime censorship in place, few of the warring powers allowed the press to report the news of the death and despair wrought by the virus in or around the frontline armies. This censorship effort did not extend to neutral Spain. The Spanish press reported extensively on the effects of the H1N1 Virus, so much so that people began referring to the virus as the “Spanish Flu,” even though the virus did not originate in said country, but the name stuck and endures.

In the meantime, while leaders like George Patton, Charles de Gaulle, Douglas MacArthur, and Winston Churchill engaged in combat on the Western Front, future President Dwight D. Eisenhower was enduring a trial by fire of his own on the old battleground of Gettysburg.

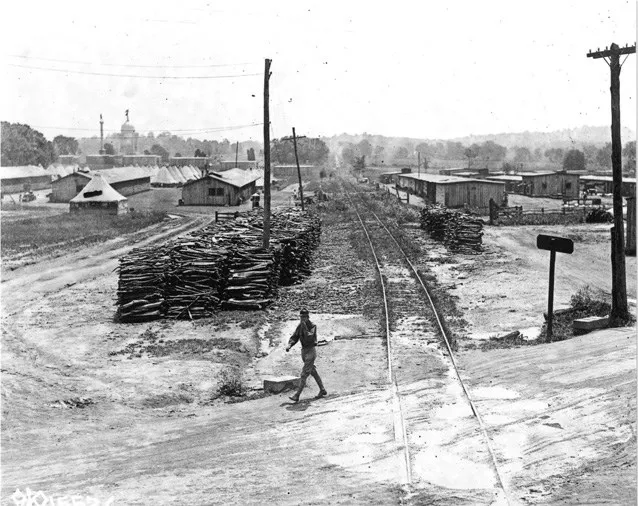

At Gettysburg, Ike was at war with a different type of foe ̶ the influenza virus. The 27-year-old Eisenhower was in charge of Camp Colt, a training facility for the newly created Tank Corps. What the camp lacked in actual tanks, as the camp contained one actually tank, it more than made up for in the training and leadership displayed by Major (later Lt. Col.) Eisenhower.

In a September 1918 troop transfer, soldiers from Camp Devens, Massachusetts, arrived at Camp Colt. These new arrivals were carriers of the flu virus. Although first misdiagnosed as having reactions to a typhoid fever inoculation, it soon became evident that Eisenhower faced a serious dilemma. By mid-October, nearly one-third were diagnosed with the flu. Eisenhower, in coordination with the Army and Gettysburg town leaders, quarantined the camp. Ike ordered that all facilities be cleaned with disinfectants daily. At first, he asked local merchants to allow only up to four soldiers at a time into their stores. Later, Ike forbade soldiers from entering the town even for church services, and he, too, forbade town members from entering the camp. The town acted, too. They helped to maintain the strict quarantine and even went as far as to cancel the annual Halloween parade. Eisenhower had the worst cases transferred off base for further isolation in Xavier Hall, which was offered for use to Eisenhower by the congregation of St. Francis Xavier Church. (St. Francis Xavier Church had housed wounded soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg 55 years prior.) On October 24th, the crisis had nearly passed, with only “one death in the past 24 hours,” and only six new cases in the camp. By the first week of November, around 150 soldiers in Camp Colt had succumbed to the Spanish flu, and Eisenhower received his orders to ship out to Europe on November 18, 1918, orders that were later rescinded with the armistice being signed on November 11, 1918. Dejected that he did not see combat in World War I, Ike nonetheless displayed the leadership qualities that would propel him to become the Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force (SCAEF), and later propel him to the White House. Ike was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by the Army for his exemplary leadership displayed at Camp Colt and during this virus outbreak.

Other United States training camps located on Civil War battlefields or named for Civil War personalities, faired far worse than had the men at Camp Colt. At Camps Forrest, Oglethorpe, Hancock, and Grant, among others, soldiers died by the hundreds ̶ reminiscent of the soldiers in blue and gray who went off to war 57 years earlier, when diseases such as smallpox, measles, and diarrhea had run rampant through their camps claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands of Yankees and Confederates.

Camp Grant located near Rockford, Illinois, and named for General Ulysses S. Grant was particularly hard hit. Camp Grant was a mixture of a training camp and a German prisoner of war camp (108 German POW’s were housed at the camp in early October). The epidemic spread quickly among the men of the 86th “Blackhawk” Division training at Camp Grant. Quarantine procedures were undertaken, but it was too late. In a letter home dated October 3, 1918, one soldier claimed that men “are dying about two an hour…” In just over three days, Camp Grant’s number of deaths reached that of Camp Colt, and by the week’s end, the number had more than doubled that of Colt. Newspapers from around the country were filled with stories of soldiers and civilians dying by the hundreds, then thousands, and then the hundreds of thousands. These papers were also filled with letters regaling friends and family at home with accounts from this new “front.”

On October 9, 1918, John McGuire wrote home to his sister, stating “[I] Was glad to hear you still all have missed the flu so far…It sure is awful here. 802 deaths up to now today. I do hope we don’t get it.” John and his brother Bud, both stationed at Camp Grant, avoided contracting the deadly virus. Sadly, hundreds of others were not so lucky. By the end of November 1918, more than 1,400 soldiers at Camp Grant and 425 civilians in the adjacent two counties succumbed to the Spanish flu.

Another victim of the Spanish flu at Camp Grant was the commanding officer of the post. Sometime between the evening of October 7 and the morning of October 8th, Col. Charles B. Hagadorn West Point class of 1889, overcome with grief and distraught by the toll the virus was taking on his men, entered his quarters and took his own life with his Colt revolver. He had been in command of the camp for less than one month. Colonel Charles W. Castle stated, “The cause of his death was due, no doubt, to a nervous collapse brought on by work and worry over the epidemic in the camp.” The Elmira, New York, native’s body was found by his men before breakfast on October 8th. The news of Hagadorn’s death was carried in newspapers across the United States and Canada. In his hometown paper, the Elmira Star-Gazette, the story of Colonel Hagadorn’s death ran side by side with a story about another Elmira soldier titled “Spanish Influenza Takes Another Elmira Soldier.”

Unfortunately, the strict discipline installed at Camp Grant by Col. Hagadorn helped to spread the virus. Although quarantined, officers were chastised by their commanding officer for “sloppy” soldiers strolling through the camp, and furthermore, these men often failed to salute a superior officer. Officers were charged by Hagadorn with punishing these men for their infractions, which led to close contact between officers and men, as well as the imprisonment of many enlisted men, which helped to spread the virus. In fairness to the officers and men of the times, how the H1N1 virus was transmitted was still something of a mystery.

While the military machine is not conducive to social distancing, it was conducive to the spread of the Spanish flu. Of the 4.7 million United States service members that served during World War I, one out of every four contracted the Spanish flu. By the end of the epidemic, some 30,000 United States soldiers died of the flu in the United States, and another 15,849 died abroad - with late September through mid-November of 1918 being the deadliest time frame for American soldiers.

Just as it had done during the Civil War and Spanish American War, and numerous conflicts before, disease claimed more American lives than did bullets, gas attacks, and cannon shells during World War I (63,114 total disease deaths vs 53,403 battlefield deaths). In conjunction with “the war to end all wars,” the Spanish flu epidemic was almost too much for the world to bear. Cities and towns at home and abroad were ravaged by loss and grief. The way people treat the spread of disease, the way that people cope with death, and even the way in which they engage with their government was strongly influenced by the Spanish flu pandemic. Communities marched off to war ̶ cousins, sons, brothers ̶ never to return with the glow of life in their eyes.

At Camp Hancock, near Macon, Georgia, Arthur Christiansen died of the Spanish flu on October 24, 1918. His brother-in-law George Hansen died the next day. They were 24 and 25 years old respectively. “With October’s blue vault above, in the fullness of the year, with the fallen leaves of unnumbered trees sounding the dirge of another season, as they rustled underfoot, they gathered at the home of Martin Hanson, drawn together by old acquaintanceship, united by marriage, and by common sorrow,” wrote the editor of the Austin Daily Herald (TX). Arthur and George’s story was just one of the thousands of its kind playing out across the United States and across the globe.

According to The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic: The History and Legacy of the World’s Deadliest Influenza Outbreak, “By the time that last fever broke and the last quarantine sign came down, the world had lost 3-5% of its population.” Sadly, the end of the First World War and the end of the quarantine from the Spanish Flu Pandemic in 1921 marked the start of the bleakest and deadliest era in human history ̶ some 71 million people were dead. And between 1921 and 1945, the world endured the Great Depression, the Holocaust, the rise of fascism, the Second World War, and the ushering in of the atomic age, leading to the loss of another 65-70 million souls.

Further Reading

- World War One Casualties by Country By: Nadège Mougel

- The United States World War One Centennial Commission By: Harry Thetford

- The Spanish Flu Pandemic Video By: United States World War One Centennial Commission

- Research Starters: Worldwide Death in World War II By: The National WWII Museum

- The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History: By John M. Barry

- The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: By Dr. Carol R. Byerly

- The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic: The History and Legacy of the World's Deadliest Influenza Outbreak: By Charles River Editors