Jackson or Longstreet: Whose Accidental Wounding was More Detrimental?

In perhaps one of the strangest Civil War coincidences, the Army of Northern Virginia lost two of its key corps commanders during friendly fire incidents in the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, almost exactly one year apart. The accidental woundings of "Stonewall" Jackson in 1863 and James Longstreet in 1864 both had significant ramifications, but which was more detrimental to the Confederates? Sam Smith and Douglas Ullman, Jr. take sides.

Two Historians Take Sides

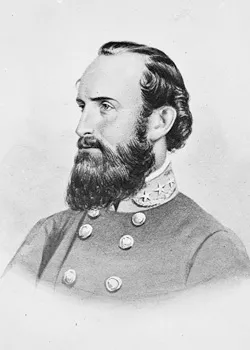

Sam Smith: Before he rode into the fading light of May 2, 1863, General "Stonewall" Jackson instructed a gathering of officers to "press right on!" At the zenith of his military career, surrounded by his men in the midst of one of their most dramatic victories, Jackson remained focused on chasing the fleeing foe and doing as much damage as possible. He rode well in front in order to find new avenues of pursuit for a moonlight coup de grace. As he returned, he was accidentally shot by his own men in the darkness.

His final instructions were disregarded in the resultant confusion. After another day of bloody frontal assaults, the Union Army was able to escape largely intact. If Jackson had been able to launch his night attack, the Union position could have been destroyed, not merely dislodged. After the battle, Union soldiers believed that they had fought well but had simply been pulled off the field too early. If they had been driven from the field in panic, the men of the Union Army would have had continued cause to doubt themselves throughout that pivotal summer. On May 2, 1863, Jackson’s fatal wounding cost the Confederacy its last chance to crush Northern morale.

Douglas Ullman, Jr.: One year and four days after Jackson was shot by his own men, the same fate befell Robert E. Lee’s Old Warhorse, General James Longstreet. Like Jackson, Longstreet was leading an attack on an exposed Federal flank, a movement which was at its height when a group of Confederates accidentally fired on their own officers. Longstreet went down with a severe neck wound which would ultimately take him out of action for six months.

As devastating as Jackson’s loss was, the damage had already been done by the time Jackson went down on the night of May 2, 1863. Jackson’s epic flank attack had already been carried out to its fullest: an entire Union corps had already been routed, and, his intentions notwithstanding, it is doubtful Jackson could have accomplished much more in the dark before his fatal wounding. On the other hand, Longstreet’s accidental wounding occurred while his men were still in the process of chasing Hancock’s Union troops back to the Brock Road. Despite Longstreet’s initial success, the men still needed a firm guiding hand to carry the assault to fruition. The sudden loss of Longstreet deprived the Confederates of that guidance. Instead of pressing their advantage, Longstreet’s wounding stopped the Rebels in their tracks, allowing the Yankees time to rally and strengthen their position on the Brock Road. It was five hours before Lee could organize a renewed effort against Hancock, and by then, the boys in blue were ready to withstand the onslaught. Lee’s chance of routing Grant in the Wilderness—of parrying the Federals’ first thrust of the campaign—went down with Longstreet on the Orange Plank Road.