July 1, 1863

Hallowed Ground Magazine, 15th Anniversary Gettysburg

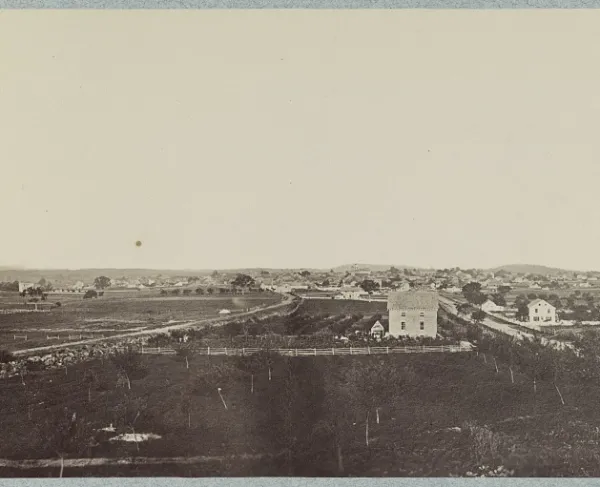

In the fields outside a small Pennsylvania town, two massive armies collided unexpectedly, provoking the bloodiest battle of the Civil War.

In mid-June 1863, lead elements of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, began crossing the Potomac River for its second invasion of the North. On June 29, newly appointed federal commander Maj. Gen. George Meade ordered his 94,000-man Army of the Potomac to pursue. In response, Lee ordered the Confederates, who had been strung in an arc from Chambersburg, Pa., to the outskirts of Harrisburg, to concentrate around Cashtown.

The following day, Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew’s brigade of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Third Corps ventured into the crossroads hamlet of Gettysburg, where it encountered a smattering of Union soldiers. Not suspecting a significant Union presence in the area, both Pettigrew and his superior officer, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, believed the horsemen to be Pennsylvania militia. Despite orders from Lee to avoid an engagement until the army was concentrated, Heth ordered two of his brigades to undertake a reconnaissance in force at first light.

In actuality, Gettysburg was occupied by two brigades of Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. John Buford, who had taken up a defensive position west of town, positioning his dismounted troopers on Herr’s Ridge. Buford sent word back of the anticipated Confederate attack, calling for swift infantry support of his position, which protected the tactically significant heights south of town.

The opening shots of the Battle of Gettysburg were fired about 7:30 a.m. The Confederates, realizing that they were facing far more than a militia detachment, dispatched additional units toward the fray. Three hours later, despite putting up determined resistance, Buford’s cavalry had fallen back to McPherson’s Ridge, but were then joined by first elements of Union infantry as Maj. Gen. John Reynolds and the I Corps arrived on the field.

Fighting extended along both sides of the Chambersburg Pike. North of the road, the Confederates saw early success, but were ultimately repulsed after suffering heavy losses around an unfinished railroad cut. South of the road, the Union Iron Brigade made significant gains, but this was tempered by the death of Reynolds, shot while leading his troops just inside of McPherson’s Woods. Fighting lulled just after noon, only to resume with renewed vigor around 2:30, with Heth’s entire Confederate division engaged. The Iron Brigade began losing ground, and when Maj. Gen. W. Dorsey Pender’s division joined the attack it was pushed back through Lutheran Seminary and into the streets of town.

Meanwhile, additional portions of both armies arrived in Gettysburg, with the Confederate Second Corps and Union XI Corps entering action north of town. The Union line was tenuous, particularly where the two corps met, a situation that the numerically superior Confederates exploited through flanking maneuvers and a pointed assault on a federal salient at a position now known as Barlow’s Knoll.

Losing ground across the field, Union commanders ordered a retreat to the formidable high ground at Cemetery Hill, south of town. Realizing the potential strength of the Union defensive position, Robert E. Lee ordered Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell to attack and seize the hill “if practicable” before the entire Union army could concentrate there. New to corps command in the army reorganization that followed Stonewall Jackson’s death, Ewell demurred — a decision that many consider one of the great lost opportunities at Gettysburg.

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...

Related Battles

23,049

28,063