The Marquis de Lafayette laying the cornerstone at Bunker Hill in 1825.

“Permit us then to receive you as the Nation’s Guest and to render to you all the honors which it is in our power to bestow on you. They are the voluntary tribute of hearts burning with gratitude. We wish our children to understand that virtue alone has the right to such homage, and that in the midst of a free people merit never stays without reward.”

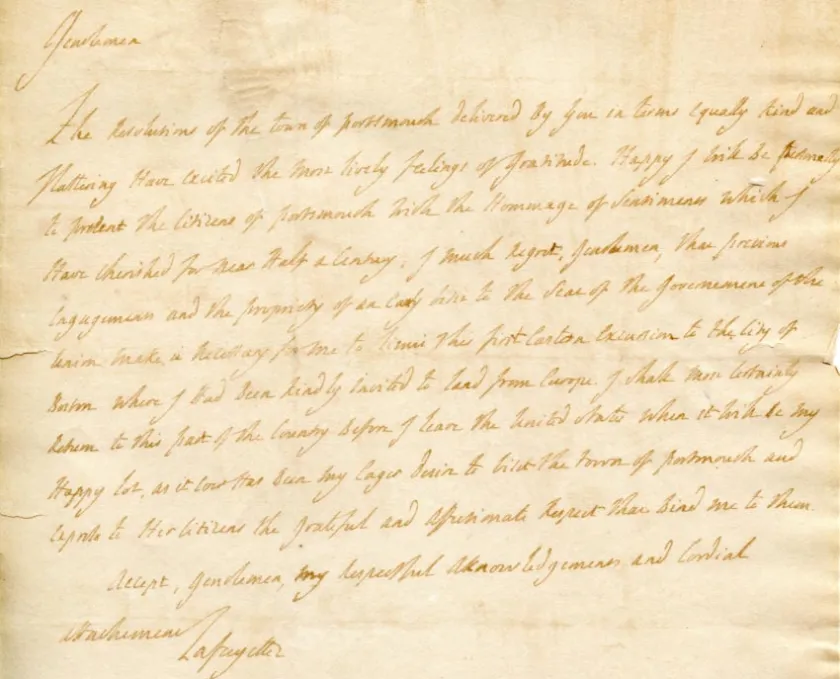

A representative from Portsmouth, NH welcoming Lafayette on September 1st, 1824.

In the early 1820s, the United States had solidified its political system and had become a nation free of any wartime binding agreement with the Republic of France. Thomas Jefferson, a lifelong friend of France, negotiated the Louisiana Purchase and secured westward expansion. The War of 1812, however, reminded the United States that homeland security needed to be a top priority for the next decades. As the generation of veterans of the Revolutionary War was wearing thin, emphasis was placed on building up national awareness capitalizing on the momentum resulting from previous conflicts. The early 1820s was marked by the Monroe Doctrine, a rationale enshrining American ambitions to secure a comfort zone around the United States of America, as the balance of power was rapidly changing in Europe.

At the same time in France, the French Revolution had brought about a new social order, which was no longer based on privileges for the few at the expense of the people of France, but rather a reshuffling of the political cards into the form of a Republic. The Marquis de Lafayette opposed the conservative Bourbon Restoration that followed the Napoleonic years but soon realized that liberal thinking had gradually weakened in France.

As the last surviving Major General of the Revolutionary War, Lafayette was invited by U.S. president James Monroe and Congress to visit the 24-state Union for what would become his Farewell Tour in the United States of America. Accompanied by his Secretary Auguste Levasseur, General Lafayette visited all the 24 states of the Union in 13 months (August 1824 – September 1825). The American experiment narrated by Levasseur was meant to serve as a driver to revive Liberals’ political views at a time when the Bourbon Restoration was stifling liberalism in France. In 1829, Lafayette started off a much smaller tour between Grenoble and Lyon in France[i] to challenge the authority of King Charles X and the secret appointment of Jules de Polignac as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

While almost 50 years had elapsed since the end of the Revolutionary War, the presence of General Lafayette in the United States unleashed a burning desire to express the peoples’ gratitude that had been building during the postwar period. Although the Farewell Tour of Lafayette is generally described as an outpouring of love and respect from the American people, looking at a specific narrative emphasizing the preparations made for the reception of Lafayette remains a unique vantage point to capture that spirit. A source documenting Lafayette’s visit to the Adams Female Academy in Derry, NH highlights the aura surrounding him when he met with local people, which granted him a godlike presence impacting not only people’s mood but also local weather.

In his Book of Nutfield [ii], George F. Willey provides a description of the preparations made to welcome Lafayette at the Academy based on a letter written at that time. “Ladies from the village now came in, hoping to share our chance of seeing the hero. After remaining an hour they departed, supposing he might have taken some other route, and that it was useless to wait any longer. But we were not so ready to relinquish our hopes, and concluded to remain.” The letter also describes Lafayette entering a classroom. “As he entered the teacher's desk I turned to look at the pupils. A magician's hand could not have effected a more sudden transformation. […] Smiles and animation had displaced fatigue and anxiety. […] Every eye glistened, but it was with enthusiasm ; every heart swelled with intense interest as we beheld the friend, the defender, the martyr of liberty.” The letter ends by emphasizing the local weather, reportedly greatly enhanced after Lafayette departed. “As he left the building, the clouds which had obscured the heavens suddenly became dissipated in the west, and although the rain still fell in torrents, the sun broke forth with unusual splendor, forming a magnificent rainbow in the east. The splendid colors of the rainbow beautifully contrasted with the masses of dark clouds that still skirted the horizon.”

In his memoirs, Josiah Quincy Jr describes the moment when Lafayette was transferred to the authorities of the Granite State upon crossing into New Hampshire at the Methuen-Salem border in June 1825. “To me his last words were ‘Remember, we must meet again in France!’ And so saying, he kissed me upon both cheeks. 'If Lafayette had kissed me,' said an enthusiastic lady of my acquaintance, ‘depend upon it, I would never have washed my face again as long as I lived!’ The remark may be taken as fairly marking the point which the flood-tide of affectionate admiration reached in those days.”[iii] This story encapsulates how people perceived Lafayette’s physical and spiritual presence during his visit, which was often characterized by the utmost desire to touch him and receive his personal blessing. Walter Harriman, who served two terms as Governor of New Hampshire, recalls the crowd in attendance when Lafayette passed through Warner, NH on June 27, 1825, “Before Lafayette could alight from his carriage, an eager crowd pressed forward to look upon his face and to grasp his hand.”[iv]

The Farewell Tour provides a unique opportunity to look at the core of American society almost 50 years after the Revolutionary War, and to assess what the country thought of itself. It taps into remote and vivid historical backgrounds and reveals how the United States celebrated one of its heroes in large cities as well as in the countryside, all across the nation.

The Farewell Tour was characterized by a fast pace as well as very frequent unscheduled stops that Lafayette made along the way.

In New England alone, Lafayette made more than 170 stops on his two visits, in August-September 1824 and June 1825. He visited people he knew from the Revolutionary War such as Caleb Stark, son of New Hampshire General John Stark, Elias Hasket Derby Jr, officer during the Revolutionary War, and James Armistead Lafayette, former slave that played a pivotal role as a double agent during the Siege of Yorktown in September/October 1781.

Many streets, cities, towns and squares across the United States today are named after General Lafayette and his La Grange castle in the outskirts of Paris. Most of those names are a direct result of the momentous Farewell Tour.

The schedule of the Tour was mostly driven by commitments Lafayette had already made, especially to large cities like Boston, New York and Washington D.C. As a result, he consistently declined a lot of invitations originating from smaller cities and towns due to their geographic location. Indeed, venturing further into the countryside carried the risk of spending time on poorly maintained roads and undergoing mechanical failures that would delay the rest of the trip.

Though many prearranged commitments were inescapable, some decisions and alterations to the existing itinerary could still be made on the fly. Lafayette, in an 1824 letter[1] to a committee from Portsmouth, NH, declines their invitation to visit Portsmouth because of previous commitments made in Washington, D.C. Notwithstanding the content of this letter, Lafayette rushed through Portsmouth in a one-day trip the same year. This letter embodies how pivotal geographic location and previous commitments were in decision-making on the Tour. The fact that Lafayette’s visit to Portsmouth lasted only one day, followed by nighttime travel to return to Boston by early the next morning, lets us capture somehow the “guilt” to have accepted an unexpected offer. The desire to catch up on the initial schedule, even if it meant spending the night in a carriage, lies behind this need to accommodate as many people as possible.

The Lafayette Trail, Inc. is a nonprofit organization with the mission to document, map, and mark General Lafayette's footsteps during his Farewell Tour of the United States in 1824 and 1825. It aims to educate the public about the national significance of Lafayette's Tour and to promote a broader understanding of Lafayette's numerous contributions to American independence and national coherence in preparation for the 2024-2025 tour bicentennial celebrations. The Trail brings together history, cartography and computer science in an education program whose principal goal is to raise awareness about Lafayette and the ideals he stood for throughout his life. It relies heavily on boots-on-the-grounds research that adds valuable materials kept in local historical societies and public libraries to the large-scale narratives covering (with much less detail) the whole trip. It features a user-friendly web-based mapping program (thelafayettetrail.org) as a tool capable of generating large interest in the French-American longstanding friendship, a powerhouse of progressivism that brought about democratic ideals still in motion around the world.

[1] The letter reads:

“Gentlemen,

The resolutions of the town of Portsmouth delivered by you in terms equally kind and flattering have excited the most lively feelings of gratitude. Happy I will be eventually to present the citizens of Portsmouth with the homage of sentiments which I have cherished for near half a century. I much regret, gentlemen, that previous engagements and the propriety of an early visit to the seat of the government of the Union make it necessary for me to limit this first eastern excursion to the city of Boston where I had been kindly invited to land from Europe. I shall now certainly return to this part of the country before I leave the United States when it will be my happy lot, as it long has been my eager desire to visit the town of Portsmouth and express to her citizens the grateful and affectionate respect that bind me to them.

Accept, gentlemen, my respectful acknowledgement and cordial attachment,

Lafayette”

[i] Jérôme Morin, Itinéraire du Général Lafayette, de Grenoble à Lyon, ed. (Lyon, France : Imprimerie de Brunet, 1829), 128p.

[ii] George F. Willey, Willey’s Book of Nutfield, ed. (Derry NH: Derry Deport, 1895), p22.

[iii] Josiah Jr. Quincy, Figures of the past, ed. (Boston, MA: Robert Brothers, 1883), p153.

[iv] Walter Harriman, History of Warner, New Hampshire, ed. (Concord, NH: The Republican Press Association, 1879), pp. 335-336.