“We Are About to Fight the Battle for Vicksburg”

Sam Smith

The Battle of Champion Hill sealed Vicksburg's fate.

The Battle of Champion Hill was precisely the battle that Ulysses S. Grant wanted to fight. From November, 1862 to May, 1863, he had struggled mightily to get his army from Memphis, Tennessee to Vicksburg, Mississippi, the formidable Southern citadel that blocked further progress down the Mississippi River. Finally, in late April, he had boldly steamed his transports right past the bristling river batteries, exchanging furious fire but successfully disembarking his men on the bramble-choked river banks south of the city. He did not immediately assault Vicksburg itself, but instead struck deeper into the Mississippi heartland, falling upon dispersed Confederate defenders with alacrity reminiscent of Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. In the first two weeks of May, his men won three battles and sowed panic throughout the state, compelling the main body of Confederates to emerge from their river fortress to confront the invaders. On May 16, on the road to Vicksburg, Grant was glad to find a diminished and demoralized foe coming to meet him in the open.

Confederate General John Pemberton was not prepared for battle. He was caught in the middle of a counter-march, with his wagons leading the army. He organized a thin blocking force on Champion Hill to hold the Jackson Road, the corduroyed path that led back to Vicksburg. The rest of his men lagged behind, command and control breaking down as an unexpected fight rumbled to life. Despite these higher-level difficulties, the riflemen defending the Jackson Road recognized the importance of their position and watched the blue lines unfold through resolute eyes.

Abraham Lincoln once called Vicksburg “the key” to winning the war. On this May morning, the Jackson Road was the key to Vicksburg. Grant hurried one division forward to pin Champion Hill while he sent one of his best divisions, under John “Blackjack” Logan, to slip beyond the Confederate flank and interdict the road from the rear. Logan made the march without delay and arrived in a striking position by 11 a.m.

As a commander, Grant was focused on results. Although he didn’t know exactly how many Confederates he was facing or exactly where they were, he knew that his actions in the campaign thus far had stimulated confusion and disorder in his foe. The attack on Champion Hill was going well, forming an excellent anvil for Logan’s hammer blow. As Logan’s lines began to form, Grant could already sense the ultimate victorious result.

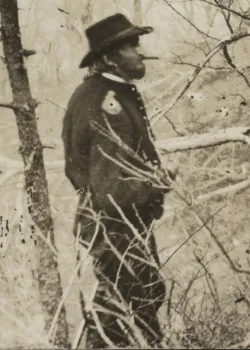

“Go down and tell Logan he is making history today,” Grant barked to an aide. Receiving Grant’s message, Logan rode to the front of his line. “We are about to fight the battle for Vicksburg,” the former Congressman shouted. Stopping in front of his old regiment, the 31st Illinois, he cried, “Thirty-onesters, remember the blood of your mammas! We must whip them here or all go to the sod together.”

Logan’s left faced the northern slope of Champion Hill and his right stretched west towards Baker’s Creek; the Jackson road ran parallel to this line about a mile distant. He had three seasoned brigades with which to assault the wooded ridge to his front. Atop the ridge, beyond the smoke rising from the picket lines, Stephen D. Lee’s Confederate brigade was likewise preparing for battle.

Before Logan ordered his men forward, Lee lunged into action, ordering the 23rd Alabama to make a pre-emptive strike to buy time for reinforcements to reach the threatened sector. The 500 Alabamians hung grimly to the task, even when they discovered 3,000 Union infantrymen waiting for them.

Logan’s Federals were surprised by the attack but well-disposed to receive it. Two batteries of cannon swung towards the rebels, and in the words of one Union soldier, “such terrible execution…I never saw. It seemed as if every shell burst just as it reached the fence, and rails and rebs flew into the air together.”

With ten Union guns in action, it is reasonable to estimate that 10 rounds were crashing into the Confederate ranks every thirty seconds. Nevertheless, the ragged 23rd pressed forward into rifle range. They were so far extended that Union soldiers were able to wrap around their flanks and pour in fire from three sides. The Confederates disappeared in an angry cauldron of black powder smoke. When it cleared, only dead and wounded bodies remained.

The survivors fell back to the wooded ridge, Logan’s men sprinting after them. One veteran later remembered the non-stop nature of this fighting. Union reinforcements surged in from both sides, crumbling Lee’s main line within half an hour. By 12:30, the Confederates were forced to retreat to another ridgeline just above the Jackson Road.

Another Confederate brigade, under Seth Barton, now pitched into the fray. He rode with three regiments directly into the teeth of Logan’s three brigades, managing to push back the first blue line before being driven back himself. With the situation growing more and more desperate, he detached one regiment, the 500-man strong 52nd Georgia, to the extreme left, further down the Jackson Road towards Vicksburg, where John Stevenson’s Union brigade was about to sever the pathway all but unopposed.

The 52nd reached the Roberts House, where eight Confederate guns were posted without support, only minutes ahead of the Union onslaught. With enemies crowding in from front, flank, and rear, the 52nd immediately charged straight ahead only to be caught in a severe crossfire and, in Stevenson’s words, “soon driven from the field.” Stevenson surged forward and soon captured the guns along with hundreds of prisoners. The Jackson Road was in Union hands.

Nevertheless, the battle’s outcome was not yet certain. Lee and Barton still clung to the ridge just north of the road, and Confederate reinforcements had finally begun to arrive. John Bowen’s veteran division crashed into action on Champion Hill, making one of the most remarkable charges of the war and suddenly threatening to open a yawning gap in the center of the Union line. The sight inspired the anxious Confederates, who rallied and reformed “as if by magic,” in Lee’s later recollection. Barton and Lee’s brigades pressed forward once more, piercing Logan’s confused line as Grant’s aides watched in horror. “The tide of battle was turning against us,” remembered a Union officer.

These minutes were anxious ones for many, but presence of mind in such situations was one of Grant’s great virtues. He knew that reinforcements were already on their way and when they arrived, he sent them forward without hesitation to hammer his line back into shape. The tide turned once more, the Confederates fell back fighting from their last ridgeline, and by 3 p.m. the Jackson Road was awash in Union blue.

The Confederates withdrew in disorder, forced to double-time along indirect paths to avoid the more advantageous Jackson Road route. The Union pursuit was vigorous and the rear-guard was shot to pieces before Pemberton’s army reached safety in Vicksburg. An entire division became separated in the retreat. “I am watching [my] career end in disaster and disgrace,” lamented Pemberton. “We are whipped,” one Confederate soldier admitted to a Vicksburg citizen.

From May 1-May 17, Ulysses S. Grant won five open field battles against the Confederate defenders of Mississippi. These battles did great damage to Confederate manpower and morale in addition to cutting off all possible routes of reinforcement, allowing Grant to lay siege to the city and accept its surrender on July 4, 1863. Up to that point, securing the Jackson Road at Champion Hill may have been Grant’s signal success of the entire campaign, decisively preventing any further concentration of forces against him and crushing Pemberton’s army without the benefit of its fortifications. The ground today holds great significance to the history of the United States.

Related Battles

2,457

3,840

4,910

32,363