Willie Hardee and the Confederates' Last Hurrah at Bentonville

Though Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston's decision to remain at Bentonville, North Carolina on March 21, 1865 despite the presence of a vastly superior Union army was based on sound reasoning, it nearly proved disastrous. Johnston wished to evacuate his remaining wounded. Abandoning them, he believed, would appear as a concession of defeat to Confederate soldiers who had routed a significant part of the Federal force on March 19. Johnston also hoped to lure his Union adversary, Major General William T. Sherman, into attempting a costly frontal assault against his stout entrenchments. (Johnston was gambling that Sherman would not test his flanks, which were far more vulnerable.) But as Sherman himself conceded, Johnston's "position is in the swamps, difficult of approach, and I don't like to assail his parapets." The third day at Bentonville therefore promised to end in a standoff between Sherman, who intended to avoid a pitched battle, and Johnston, who hoped to tempt the Federals into assaulting him head-on. In any event, a steady rain began to fall about midday, rendering a general engagement highly unlikely. One of Sherman's staff officers noted that "there is no prospect of an assault," and that the fighting would be limited to skirmishes "intended to reconnoitre the ground."

Neither the rainfall nor Sherman's caution could dampen the martial ardor of the Federal army's most aggressive division commander, Major General Joseph A. Mower. As Mower led his command, the First Division of the Seventeenth Corps, into position on the Union right flank near Bentonville, he stopped to confer with Seventeenth Corps commander Major General Frank P. Blair. Mower obtained permission from Blair to make "a little reconnoisance" once his command reached its assigned position. Soon afterward, Mower and two of his brigades (the third brigade was on wagon train guard duty several miles to the rear) reached the Union right flank. The division commander ordered his entire force to cross a swamp and attack the Confederate line in the belief that the Rebel force in his front was bound to be weaker than his own. Mower was right, for only a thin skirmish line of poorly entrenched cavalry stood between the Federals and the Mill Creek bridge, Johnston's only line of retreat. At noon, Mower ordered his command to advance in line of battle, and his "little reconnoisance" was underway.

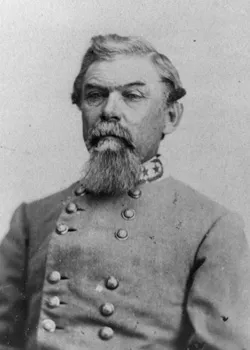

While Mower and his troops slogged through the swamp, Johnston's chief of cavalry, Lieutenant General Wade Hampton, galloped to the Confederate commander's headquarters, reporting that Federal troops were advancing in strength toward Bentonville. Hampton warned Johnston "that there was no force present able to resist an attack, and that if the enemy broke through at that point, which was near the [Mill Creek] bridge...our only line of retreat would be cut off." "Old Joe," realizing that he had to shift troops from other parts of his line in order to strengthen his weak left flank, gave the necessary orders. Johnston entrusted the defense of the endangered flank to his senior corps commander, Lieutenant General William J. Hardee.

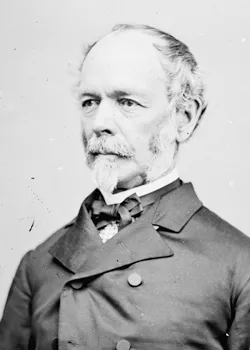

The forty-nine-year-old Hardee was a graduate of West Point and had been a professional soldier for the past twenty-seven years. Hardee was nicknamed "Old Reliable" by his men, whom he had commanded in nearly every major battle of the Western Theater, from Shiloh to Jonesboro. On March 16, 1865, Hardee had acquitted himself superbly in his only independent command of the war, leading his heavily outnumbered corps in a delaying action near Averasboro, North Carolina against the left wing of Sherman's army. Hardee's success in halting Sherman's advance for one day made possible Johnston's assault on the left wing at Bentonville on March 19. Furthermore, Hardee's conduct in the first day's fighting at Bentonville was heroic. When his advancing troops faltered before a large open field as they glimpsed the blue tunics and flashing bayonets of Union troops along the opposite tree line, Hardee rode out into the field and waved his men forward, rallying the charge.

On the afternoon of March 21, Hardee faced an especially difficult assignment, for as he oversaw the defense of the Confederates' left flank, the general was no doubt preoccupied with the welfare of his only son, sixteen-year-old Willie Hardee. Willie was the newest, and probably the youngest, recruit of the Eighth Texas Cavalry—the renowned Terry's Texas Rangers. In the spring of 1864, Willie had glimpsed the Rangers as they rode past his Georgia school and was so captivated by their appearance that he ran away to join the regiment. The Rangers' commander turned Willie over to his father, who made the youth a lieutenant on his staff—the better to keep an eye on him. During the Atlanta Campaign, Willie frequently came under fire while in the line of duty and once had a horse shot from under him.

In February 1865, Willie had left his father's staff to enlist as a private in an artillery battery, but the boy soon found artillery service as safe—and as dull—as school life back in Georgia. During the march from Averasboro to Bentonville, Willie again met the Rangers, and in the words of Hardee's adjutant, "the boy's first love revived." Willie begged his father to let him join, and the elder Hardee at last relented. "Swear him into service in your company," the general told the Rangers' Captain Kyle, "as nothing else will satisfy."

The Eighth Texas Cavalry was drawn up in reserve, the men either resting or feeding their horses, when Willie Hardee joined them. Willie was regaling the Rangers with the latest headquarters gossip "when a sharp rattle and then a roar was heard [coming from] the [Mill Creek] bridge," recalled one of the Texans. "There was no mistaking what it meant." As General Hardee anxiously awaited his reinforcements, Mower's two brigades emerged from the swamp, struck the thin line of Confederate cavalry, and routed the dismounted horsemen in their immediate front. The cavalry on Mower's flanks fell back in confusion and attempted to rally for a counterattack. Some of Mower's skirmishers overran Johnston's headquarters and pursued the Confederate commander and his staff toward Bentonville and the Mill Creek bridge. Meanwhile, one of Hardee's staff officers galloped up from the direction of Bentonville and ordered the Eighth Texas Cavalry and the Fourth Tennessee Cavalry regiments to mount up and follow him, for they were needed to save the bridge.

About a half-mile from their resting place, the two cavalry regiments were halted by General Hardee himself, who "at once ordered the regiments into line along the road and to charge through the woods," recalled the historian of the Fourth Tennessee Cavalry. The Eighth Texas deployed on the right and the Fourth Tennessee on the left. One of the Texans noticed that as Private Hardee took his place in the front rank, the general and his son tipped their hats to each other. For a moment there was a terrible stillness: "Everything was so plain and clear," remembered one Ranger, "you could see the [Yankees] handling their guns and hear their shouts of command." Drawing his sword, General Hardee gave the order and personally led the charge. "With a wild shout we rushed through the woods," recalled a veteran of the Fourth Tennessee. As the Confederate riders thundered down upon the Union infantry, they fired their rifles and carbines at the approaching blue line, then tossed them aside and grabbed their revolvers. Overwhelmed by the suddenness of the Rebel onslaught, the Federal skirmishers fell back toward the main line. As part of a motley strike force of cavalry and infantry hastily deployed by Hardee and his staff, the Eighth Texas and Fourth Tennessee wreaked havoc along the left of Mower's line, killing or capturing dozens of Union skirmishers.

At least one Ranger got more than he bargained for when he overtook a squad of Yankees with some fight left in them. The bluecoats answered the Texan's demand to surrender by firing a few shots in his direction, convincing the Southerner that "they were not a surrendering lot." The veteran cavalryman recollected that, "of all the simple acts of my life, this one headed the list....After this bullets seemed to make a greater noise than usual."

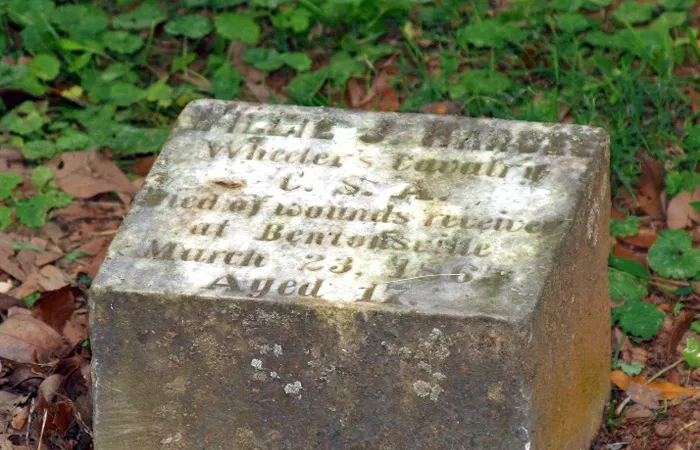

After disengaging, Mower reformed his two brigades and prepared to resume the offensive. But he received orders from Sherman to halt and dig in. Thus ended the engagement known as "Mower's Charge." If Mower was bitterly disappointed with the outcome of his attack, his Confederate counterpart, General Hardee, could not have been more delighted. As "Old Reliable" trotted to the rear—"his face bright with the light of battle"—he turned to Hampton and said, "That was Nip and Tuck, and for a time I thought Tuck had it." But Hardee's triumph abruptly darkened into tragedy when he saw Willie slumped over in his saddle, held up by a Ranger who rode behind him. Willie Hardee had received a mortal chest wound. As his father looked on, Willie was placed on a stretcher and carried to a waiting ambulance. Hardee ordered that his son be transported to Hillsborough, where his wife and daughter were staying with the family of his niece, Susannah Hardee Kirkland, the wife of Brigadier General William W. Kirkland. Willie lingered a few days before dying on March 23, less than three weeks before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House.

At least one of the enemy mourned Willie's death. During the 1850s, Willie's father had befriended a young lieutenant who later rose to the rank of major general in the Union army. That officer was Oliver O. Howard, who commanded the right wing of Sherman's army at Bentonville, and whose command included Mower's division. Despite considerable differences in age, rank, and temperament, Howard and Hardee had been close friends at West Point. Hardee, the commandant of cadets, had even entrusted Howard, a lowly assistant professor of mathematics, with tutoring his son Willie. Howard received the news of Willie's death from a West Point classmate, Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee, one of Johnston's corps commanders.

Willie Hardee was given a military funeral, attended by his father as well as many former comrades from Hardee's artillery. Willie was buried in the cemetery of Saint Matthew's Episcopal Church in Hillsborough.

Mark Bradley is the author of Last Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville, This Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Place, and Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians in Reconstruction South Carolina.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...