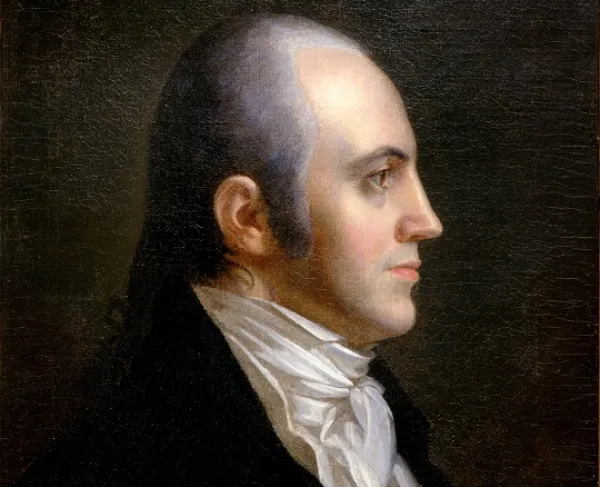

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr’s legacy as a founding father is peculiar. He was a hero of the Revolutionary War, United States senator, and vice president. Although, at the time of his death, he was a debtor, tried on charges of treason, and had few friends left, Burr was once a famous American hero. But from his late life to his modern-day legacy, Burr, like Benedict Arnold, has become a symbol of American infamy.

Burr was born into a family of very high regard. His father, Aaron Burr Sr. was a prominent Presbyterian minister and the second president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). His mother, Esther Edwards Burr, was the daughter of Jonathan Edwards, the most famous American theologian. Aaron Burr was born on February 6, 1756, in Newark, New Jersey. Burr’s father died when he was only one year old, and his mother died the following year. Burr became an orphan at the age of two years old. After the death of his parents, Aaron and his sisters moved in with their grandparents, yet by the time Burr reached the age of four years old, both his grandparents had died as well. For the majority of Burr’s youth, he would spend living with his uncle, Timothy Edwards. Timothy was a successful lawyer and provided for Aaron’s early education, hiring Princeton trained tutors to educate him until he could attend Princeton.

At age 11, Burr applied for Princeton, though initially turned away, he applied two years later at age 13 and was accepted. Burr studied theology at Princeton, but at age 19 his passions shifted, and he moved to Connecticut to study law. With news of colonial protest, along with reports of the Continental Congress, he became increasingly restless. Finally, upon learning of Lexington and Concord in 1775, Burr left his studies for the life of a soldier.

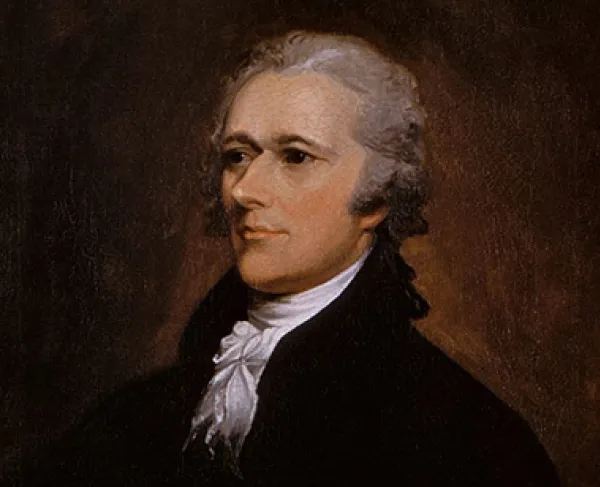

Burr’s career in the Continental Army was long and prosperous. Burr first served under, then patriot, Benedict Arnold. Under Arnold’s command, Burr participated in the American invasion of Canada. Burr was one of many volunteers who marched 350 miles through the northern wilderness to Quebec City. While the expedition was disastrous for the American army, it was fortuitous for the young officer. When the soldiers arrived in Quebec, Burr was appointed General Richard Montgomery’s aide-de-camp. Burr became a near-fantastical hero in the wake of the battle, after reports that General Montgomery had died in Burr’s arms, and that Burr had tried to save Montgomery’s body, but the piling snow prevented him from carrying the lifeless body any further. Future Hamilton ally Theodore Sedgwick wrote letters to Burr praising his, “young, gay, enterprising martial genius.”

After a very brief stint on George Washington’s staff in Manhattan, Burr was assigned to General Israel Putnam, who made Burr his aide-de-camp. Burr was a crucial leader in the American retreat from New York. Burr designed the safe route out of the city, guiding 5,000 men to safety and salvaging US artillery. In 1777, partly because of his command in the retreat of New York, Washington promoted Burr to lieutenant colonel, and he assumed command of more than 300 men. As lieutenant colonel, Burr fought off raids into New Jersey by the British and defended a pass into Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778. After the defeat at the Battle of Monmouth and mounting health problems, Burr resigned from the Continental Army in 1779.

Burr continued his study of law and was admitted to the bar in New York in 1782. He began a successful career as a lawyer and used this to launch himself into early New York politics. From 1784 to 1785 Burr served in the New York State Assembly. In 1789, Burr was appointed the New York State Attorney General. He used these stations and popularity in New York to successfully defeat powerful and wealthy Phillip Schuyler in 1791 to become a senator of New York. By 1796 Burr had become a successful and popular senator and an important Democratic-Republican. He attempted a run for president, but to his dismay, placed fourth, behind John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Pinckney. In 1800 Burr ran again, intending to become Jefferson’s vice president. However, Burr and Jefferson tied in electoral votes meaning the House of Representatives would decide the president. Burr had the opportunity to concede the election but instead remained silent. He might have believed he had a chance at the presidency, as some prominent Democratic-Republicans such as William P. Van Ness and Edward Livingston wanted Burr as president. However, due to the ardent opposition of Alexander Hamilton, Jefferson was chosen as president and Burr as vice president.

Burr was a judicial vice president. While Thomas Jefferson distrusted Burr and barred him from the politics of the White House, Burr presided over the Senate masterfully. Most notably in the impeachment trial of Federalist Justice Samuel Chase. Jefferson had grown weary of the power of the judiciary and sought to reduce Federalist influence on the Supreme Court by removing Samuel Chase by exploiting earlier failures of the justice. After the House voted to impeach Chase, Chase’s impeachment was to be decided by the Senate and presided over by Burr. Despite pressure from Jefferson, Burr handled the case as fair as possible. One Washington newspaper, typically critical of Burr, remarked, “He conducted (the hearings) with the dignity and impartiality of an angel, but with the rigor of a devil.” Because of the Vice President's impartiality in the trial, a Democratic-Republican majority voted to acquit Chase on all charges.

The Samuel Chase trial would be Burr’s last real success. After the trial, Jefferson made it clear that Burr would not be his running mate in the election of 1804. Burr turned his ambitions to running for Governor of New York in the same year, however Alexander Hamilton and fellow Federalists mounted a vicious campaign against Burr, even publishing Hamilton’s private remarks that Hamilton believed “Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government.” After Burr read the remarks of his longtime rival, he sent a series of letters to Hamilton, eventually issuing a formal challenge to duel. Hamilton accepted the challenge, and on the morning of July 11, 1804, the two longtime rivals met in the Heights of Weehawken New Jersey. Much has been said and written about the duel, and history is still ambiguous on who shot first, whether Hamilton intended to waste his shot, and even who stood facing the sun. However, what is clear, from all accounts, is that two shots were fired, Hamilton missed, Burr did not. Burr’s shot entered Hamilton above his right hip, injuring his liver and spine. Hamilton died the next day. New York and New Jersey charged the Vice President with murder; however, neither went to trial and charges were later dropped.

After Jefferson dropped Burr as his running mate and Burr lost the New York gubernatorial election, he left for the west in 1805. While his ambitions for his journeys west remain unclear, his accusers believed that he wanted to steal parts of the Louisiana Territory along with Spanish lands to form an independent nation. During his journeys west, Burr made contacts with British officials, Spanish ministers, and even Mexican revolutionaries. Many of these connections accused Burr of promising a new nation and even discussed conquering Washington D.C. Burr’s actions did not go unnoticed, many newspapers and the District Attorney for Kentucky reported to Jefferson of Burr’s plans. Finally, when James Wilkinson, one of Burr’s co-conspirators, produced a letter accusing Burr of treason, Jefferson immediately ordered his former Vice President be arrested. Burr was arrested and put on trial with charges of treason. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall acquitted Burr, arguing that there was a lack of evidence against Burr and that he committed conspiracy, but he did not take any action against the US government. Despite being acquitted, the trial completed destroyed Burr’s political career and public image.

Burr’s retirement became a tragic story of a failed man trouncing about the world looking for any modicum of success. He left the United States in 1808 traveling to England in hopes of receiving support for a Mexican revolution. British officials ordered Burr out of the country, so he fled to France to seek Napoleon’s support of a revolution, the French were similarly uninterested in the plot. Too poor to finance a journey home, the once powerful statesman waited in France until 1811 when a French ship was able to take him back to the United States. Back home, Burr changed his last name to “Edwards” and resumed practicing law. In 1833 he married wealthy socialite Eliza Jumel. However, the marriage was short-lived as Burr wasted her wealth. Burr died deeply in debt on September 14, 1836, the same day his wife’s divorce was granted.

Burr was once an American hero. However, from his duel with Hamilton on, Burr saw his career rapidly deteriorate and lost everything—power, station, wealth, and even his heritage through his last name. Burr was once an American hero but died an iconic American villain.

Related Battles

515

19