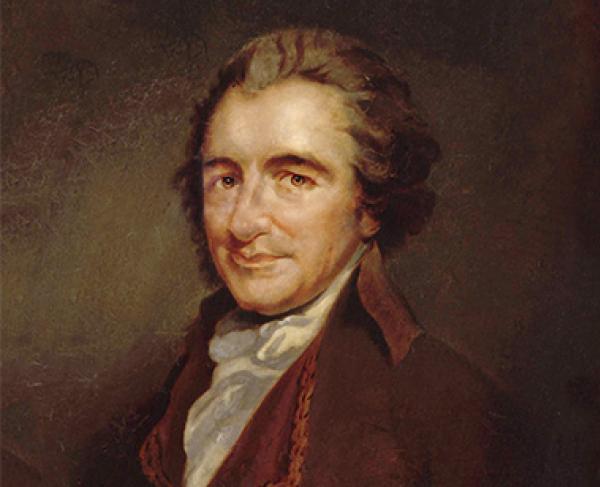

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine grew up in a household of modest means, and only came to America a year before the start of the Revolutionary War at the age of 37. Yet, before long, his writings had set the continent aflame and Paine established himself as the preeminent voice for independence from Great Britain, and later as one of the great Enlightenment thinkers on either side of the Atlantic.

Born in February 9th, 1737 in a small town in Norfolk, England, Paine spent much of his childhood as an apprentice to his father, a stay-maker for sailing ships. Later writers helped spread the idea that Paine and his father made stays, or wiring, for women’s corsets, but this is likely a myth, originating as a cruel joke at Paine’s expense by his political opponents. He did, however, receive some schooling, as until the age of thirteen he attended the local grammar school where he learned to read and write. His parents also played a strong role in his upbringing, with his ostracized Quaker father instilling many of those values in him, while his Anglican mother taught him the Bible. But the qualities that made him truly famous, his rhetorical flourish and his passion for human dignity, he learned not in school, but through decades of experience laboring for himself and others as a customs officer, privateer and school teacher, to name a few. Seemingly incapable of settling down for long, Paine crisscrossed England from his Norfolk home to Kent to Cornwall to London before finally moving to Lewes, a small Sussex town near the Channel coast, where his writing career began.

Before his appointment at Lewes, Paine was relatively uninterested in politics, but through his many travels he had taken notice of the deep divide between wealthy and poor in his society, despite much pretense about “English Liberties” bandied about by those wealthy enough to afford them. Upon moving to Lewes, therefore, Paine used his new side career to advocate for the welfare of his fellow excise officers. At this point, it might be easy to characterize Paine as a rough-and-ready working-class hero, but that does not nearly paint a full enough picture. Though he kept his style unpretentious and accessible for less educated readers (his father even forbade him from learning Latin to prevent snobbery), Paine demonstrated interest in a variety of academic subjects. The theories of Isaac Newton greatly inspired him, and Paine closely followed all recent scientific and technological developments whenever he was in London. He also remained fairly well-connected to some of the leading minds in Britain, including Philadelphia publisher Benjamin Franklin, who at the time was in London to lobby Parliament in the interests of the American colonies. But despite his connections, Paine honed a relatively radical edge to his rhetoric, taking on Lewes’ history as a former hotbed of Republicanism during the English Civil War a century prior as an influence.

In 1774, Franklin made an offer to Paine to come to Pennsylvania. By then, there was very little holding Paine to England: his first wife, Mary Lambert, died in childbirth six years prior, and his second wife, Elizabeth Ollive, left him after his new obsession with political advocacy led to his sacking. With the aid of some wealthy friends, Paine gathered what he could and paid for a voyage across the Atlantic.

Typhoid fever nearly killed Paine while during the crossing, but once he recovered, he soon began making a living as writer and editor for the Pennsylvania Magazine. In contrast to his fellow Englishmen, American colonists were on average wealthier, more literate and more politically engaged, meaning that Paine had a more receptive audience, which contributed to his popularity. For his part, Paine took a strong liking to Philadelphia society and more broadly, the discontent against Great Britain that had been simmering since the end of the Seven Years War (French & Indian War).

Though the First Continental Congress had already convened by the time of Paine’s arrival in America, many of the leading Patriot voices were uncomfortable to fully come out in support of independence, even after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Their general complaint had always been that their natural rights as British subjects had been violated by Parliament, and they wished to see those wrongs rectified. Paine’s far more radical outlook led him to see the situation quite differently, and so he set out to make the case for independence and describe his vision for America’s political future in his most famous work: the 47-page pamphlet titled “Common Sense.”

Published on January 10th, 1776, “Common Sense” decries not just British tyranny, but the concept of monarchy itself, and calls for the formation of an American republic in the purest sense of the word: a government run as a res publica, or “public affair.” Paine’s radical rhetoric and skillful argumentation electrified the colonies, and “Common Sense” quickly became one of the best-selling written works in America, followed only by the Bible. As one Connecticut reader wrote to a Philadelphia newspaper, “We were blind, but on reading these enlightening words the scales have fallen from our eyes.” Seven months after the publication of “Common Sense,” the Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence, announcing their intention to formally sever ties with Great Britain.

Paine’s writing career did not stop as the war progressed, however. Between 1776 and 1783, he published a series of smaller pamphlets collectively titled “The American Crisis.” The first issue of the series was published during America’s lowest point in the war, as the British crushed General George Washington and the Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island and forced him from New York City. With news of rampant desertion plaguing Washington’s army reaching Philadelphia, many of Paine’s associates may have predicted a swift end to the Revolution, but Paine manages to find a grim resolve in the desperation, writing, “These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.” On the 23rd of December, two days before Christmas, Washington had the pamphlet read to his cold, starving troops in a last-ditch attempt to boost their morale. The gambit worked, and two days later, Washington crossed the Delaware River with his army and ambushed a Hessian garrison at the Battle of Trenton the next morning. The Revolution had been preserved for just a little while longer, thanks in part to Paine’s prose.

Though he worked to aid the war effort in several other ways, Paine eventually returned to England in 1787, where yet another Revolution caught his attention, this time in the heart of European Absolutism: France. In 1791 and 1792, partially in response to Conservative politician Edmund Burke’s published views on the subject, Paine defended the ideals of the French Revolution by publishing his most comprehensive work yet, Rights of Man. Dedicated to Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette, Rights of Man extensively lays out Paine’s Republican utopianism and envisions a society where man’s natural rights are respected, all forms of hereditary government such as monarchy and aristocracy are abolished, and the welfare of the poor are taken care of. Paine’s work resulted in him receiving honorary French citizenship as a reward, as well as a seat on the French Constitutional Committee.

In France, Paine wrote several other important works, such as “Age of Reason”, which discusses his personal theology of deism (belief in a single God as a distant, unknowable entity) and “Agrarian Justice”, which expounds upon his almost proto-socialist economic views. Despite his support, however, Paine ran afoul of the Jacobin Party which took control of the French government after King Louis XVI’s execution. He was arrested and slated to be executed himself, but the government delayed the date long enough for the American Minister to France, James Monroe, to secure his release. His ordeal in prison could not suppress his political idealism, however, and Paine continued to interact with some of the leading figures of France, including a chance meeting with the ever more popular General Napoleon Bonaparte, who claimed to sleep with a copy of Rights of Man under his pillow. Paine, of course, later denounced Bonaparte as a charlatan when the latter established his military dictatorship in late 1799.

Finally bereft of all hope for France, Paine returned to America in 1802, but found that he did not receive nearly as warm a welcome as a former intellectual champion of liberty might expect. His published criticisms of President’s Washington and John Adams alienated him from the Federalist Party, while his deism made him a hated figure by the religious community. Paine continued to write and publish until the end of his life on June 8th, 1809, when he died in New York City. His funeral was poorly attended, and a local paper summed up his life as having done “some good and much harm,” but in time, Paine’s work proved to be a great inspiration to politicians and activists alike in the coming centuries, Abraham Lincoln among them. As John Adams once wrote, “Without the pen of the author of ‘Common Sense’, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.”