Antietam

Sharpsburg

Washington County, MD | Sep 17, 1862

Antietam, the deadliest one-day battle in American military history, showed that the Union could stand against the Confederate army in the Eastern theater. It also gave President Abraham Lincoln the confidence to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation at a moment of strength rather than desperation.

How it ended

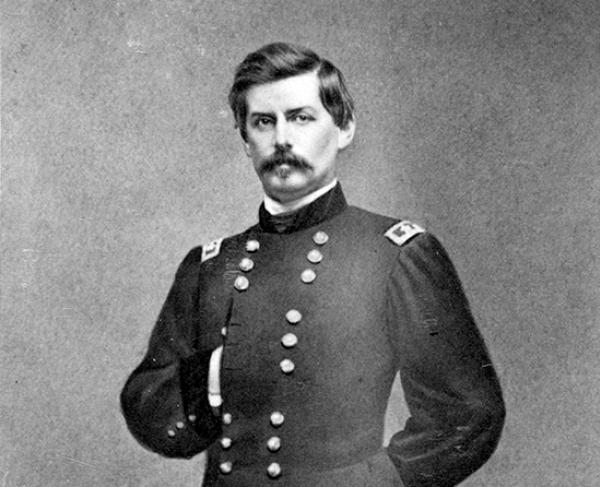

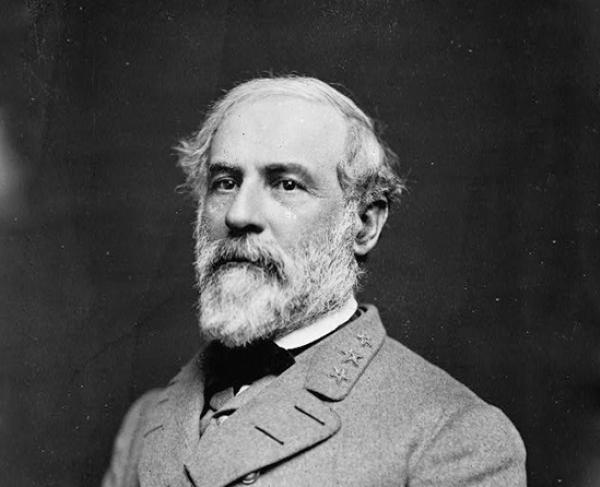

Inconclusive. General Robert E. Lee committed his entire force to the battle, while Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan sent in less than three quarters of his. With the full commitment of McClellan’s troops, which outnumbered the Confederates two to one, the battle might have had a more definitive outcome. Instead, McClellan’s half-hearted approach allowed Lee to hold ground by shifting forces from threat to threat.

In context

Lee invaded Maryland in September 1862 with a full agenda. He wanted to move the focus of fighting away from the South and into Federal territory. Victories there, could lead to the capture of the Federal capital in Washington, D.C. Confederate success could also influence impending Congressional elections in the North and persuade European nations to recognize the Confederate States of America. On the other side, President Abraham Lincoln was counting on McClellan to bring him the victory he needed to keep Republican control of the Congress and issue a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

The first Confederate invasion of Union-held territory is not going as planned. After a Union victory at the Battle of South Mountain and a Confederate victory at the Battle of Harpers Ferry, Confederate general Robert E. Lee opts to make one last stand in the hopes of salvaging his Maryland Campaign.

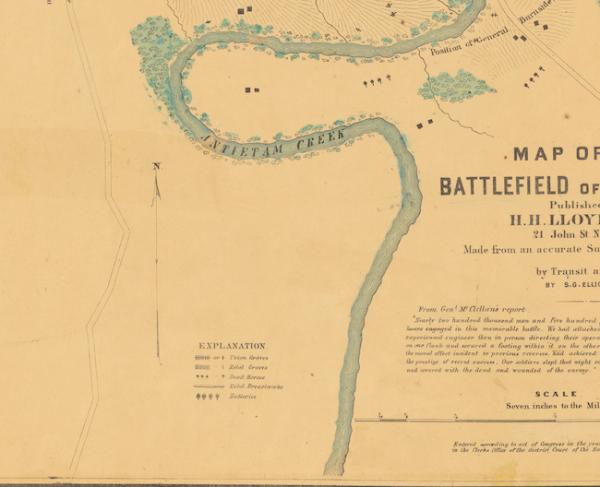

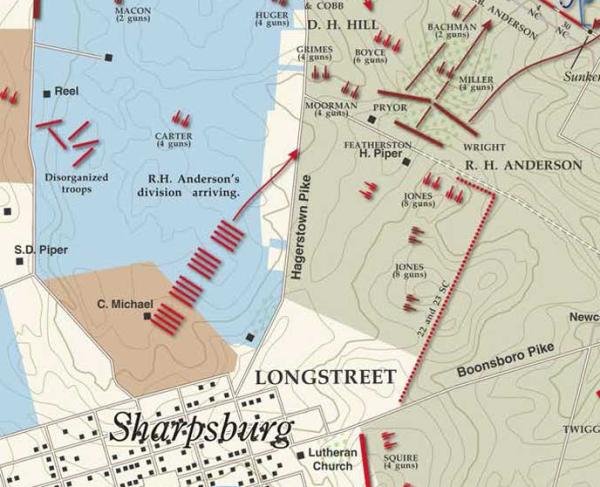

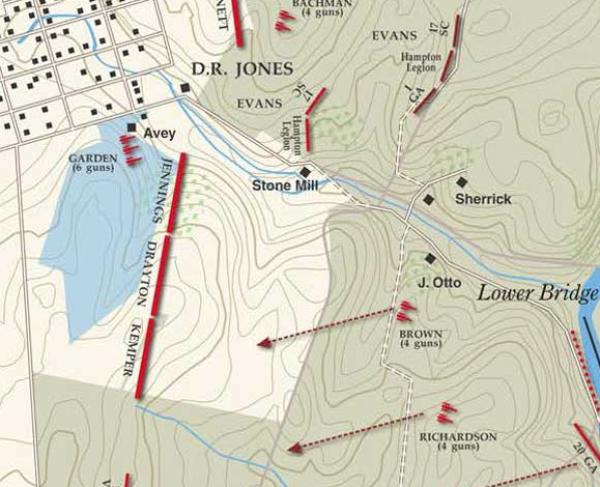

With Federal forces closing in from the east, Lee selects strategic ground near Antietam Creek and orders his army to converge there. A mile east of the town of Sharpsburg, the creek meanders through the hilly but open countryside, good for long-range artillery and moving infantry. The water is deep, swift, and crossable only at three stone bridges, making it a natural defensible location. On September 15, Lee positions his men behind the creek and waits for McClellan to arrive.

On the afternoon of September 16, Union general George B. McClellan sets his army in motion, sending Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s First Corps across Antietam Creek to find Lee’s left flank. At dusk, Hooker bumps into Confederate general John Bell Hood’s division and the two forces skirmish until dark. The following morning, McClellan attacks.

September 17. The Battle of Antietam begins at dawn when Hooker’s Union corps mounts a powerful assault on Lee’s left flank. Repeated Union attacks and equally vicious Confederate counterattacks sweep back and forth across Miller’s cornfield and the West Woods. Hooker sees thousands of his Federals felled in the corn rows, where, “every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before.” Despite the great Union numerical advantage, Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate forces hold their ground near the Dunker Church.

Meanwhile, towards the center of the battlefield, Union assaults against the Sunken Road pierce the Confederate center after a terrible struggle for this key defensive position. Unfortunately for the Union, this temporal advantage in the center is not followed up with further advances and eventually the Union defenders must abandon their position.

In the afternoon, the third and final major assault by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's Ninth Corps pushes over a bullet-strewn stone bridge at Antietam Creek. (Today it’s called Burnside Bridge.) Just as Burnside's forces begin to collapse the Confederate right, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s division charges into battle after a long march from Harpers Ferry, helping drive back the assault and saving the day for the Army of Northern Virginia.

12,401

10,316

There are more than 22,000 casualties at the Battle of Antietam. Doctors at the scene are overwhelmed. Badly needed supplies are brought in by nurse Clara Barton, known as the “Angel of the Battlefield.” During the night, both armies tend their wounded and consolidate their lines. In spite of his diminished ranks, Lee continues to skirmish with McClellan on September 18, while removing his wounded south of the Potomac River. Late that evening and on September 19, after realizing that no further attacks are coming from McClellan, Lee withdraws from the battlefield and slips back across the Potomac into Virginia. McClellan sends Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter to mount a cautious pursuit, which is repulsed at the Battle of Shepherdstown.

While the Battle of Antietam is considered a tactical draw, President Lincoln claims a strategic victory. Lincoln has been waiting for a military success to issue his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He takes his opportunity on September 22. The Proclamation, which vows to free the slaves of all states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, will forever change the course of the war and the nation by marrying the Union cause with an attack on the institution of slavery. Hesitant to support a pro-slavery regime, England and France decline to form an alliance with the Confederate States of America.

After McClellan fails to pursue Lee on his retreat south, Lincoln loses faith in his general. Weeks later, he names Burnside commander of the Army of the Potomac.

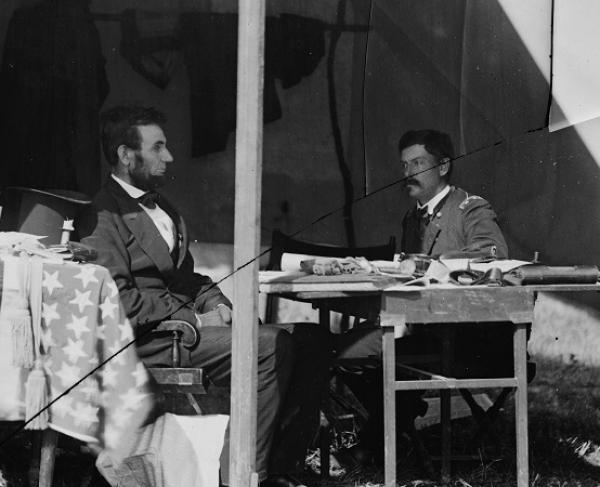

Lincoln and McClellan had a tortured relationship. McClellan’s letters reveal his contempt for his commander-in-chief (whom he sometimes referred to as “the Gorilla”), and the historical record shows that as the war slogged on, Lincoln became increasingly frustrated with his general’s timidity and excuses. He believed McClellan spent too much of his command drilling troops and little of it pursuing Lee. Lincoln called the general’s “condition” a bad case of “the slows.”

Though well-liked by his men, McClellan could be vain and boastful. After he failed to attack Lee’s depleted troops as they fled Sharpsburg on September 18, he wrote to his wife, Ellen, that, ''those in whose judgment I rely tell me that I fought the battle splendidly & that it was a masterpiece of art.'' Lincoln disagreed. He could not understand why his general was not on the tail of the Confederates, and he went to McClellan’s headquarters at Antietam to light a fire under him. In a letter to his wife, Mary, Lincoln joked, “We are about to be photographed. . . [if] we can sit still long enough. I feel Gen. M. should have no problem.”

Six weeks after Antietam, McClellan finally heeded his boss’s advice and led the Army of the Potomac into Virginia, but at a snail’s pace. Even before the nine-day trek, Lincoln had all but given up on the man who had once been christened “Young Napoleon” for his military promise. The president relieved McClellan of his duties on November 7 and appointed Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside to be his replacement.

After losing his command, McClellan took up a new career—politics. In the 1864 election he was the Democratic nominee for president of the United States. His opponent, Abraham Lincoln, was reelected for another term.

Clarissa “Clara” Harlowe Barton was a former teacher and patent clerk who became a nurse on the front lines during the Civil War. Despite having no prior experience and receiving no payment for her services, she bravely drove her cart of medical supplies into the fray at many battles, including Antietam. She saw the desperation of the wounded and dying and did what she could to aid and comfort them. Dr. James Dunn, a surgeon at the Battle of Antietam lauded her efforts:

The rattle of 150,000 muskets, and the fearful thunder of over 200 cannon, told us that the great battle of Antietam had commenced. I was in the hospital in the afternoon, for it was then only that the wounded began to come in. We had expended every bandage, tore up every sheet in the house, and everything we could find, when who should drive up but our old friend, Miss Barton, with a team loaded down with dressings of every kind, and everything we could ask for. . . .In my feeble estimation, General McClellan, with all his laurels, sinks into insignificance beside the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battle field.

Later in the war, Lincoln authorized Barton to form the Office of Correspondence with Friends of Missing Men in the United States Army, an effort that eventually identified 22,000 missing Union soldiers. In 1881 Barton founded the American Red Cross.

Antietam: Featured Resources

All battles of the Maryland Campaign

Related Battles

87,000

45,000

12,401

10,316