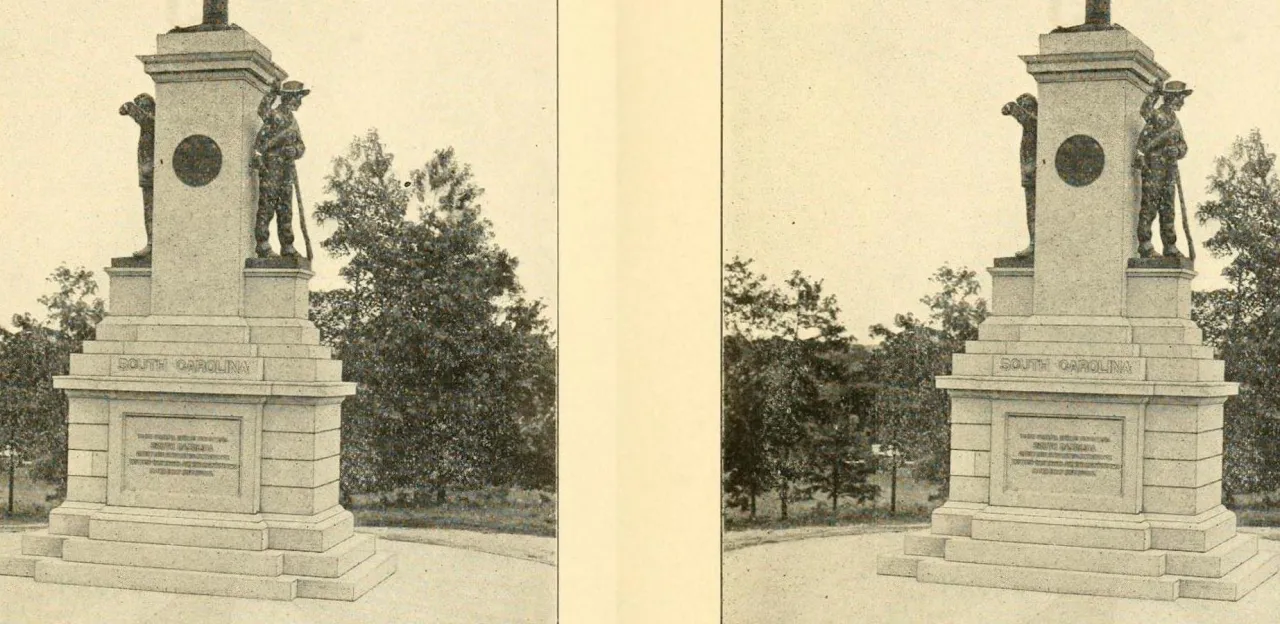

Second Dedication Speech for the Unveiling of the South Carolina Monument on the Chickamauga Battlefield

Address of Confederate General, C. I. Walker’s Address, during the deciation ceremony of the South Carolina Monument at Chickamauga:

Fellow Citizens and Comrades: On this great battlefield, thousands of thrilling and valorous events crowd, each (12) vieing [sic] with the other in glory and honor to the brave soldiery who have made the name of "Chickamauga" glorious through all time. Few of these splendid achievements could have come under the ken of any one man. So, if we desire to portray the truth, we must rely for the movements of each command upon the statements of those who participated therein, and even then upon the character of the witness. Realizing this, my statements as to the part taken by each of the noble bodies of South Carolinians who, on this field, won immortal fame, are based on those given me by men who were with each in the battle and whose character is such that whatever they may say carries the conviction of truth.

For the general history of the field we have the "War of the Rebellion Records," which contain the reports of the officers made soon after the occurrence of events. In these there are naturally mistakes, but on the whole they are as nearly correct as could be expected. In addition to this valuable source of general information, for the special part taken by each command, I am indebted as follows: For that of the 24th South Carolina regiment to the gallant Gen (Bishop) Ellison Capers, whose fealty to the Confederacy is only excelled by his loyal faith to his God. For that of Kershaw's Brigade to Capt. D. A. Dickert's admirable "History of Kershaw's Brigade," to Gen. Longstreet's "From Manassas to Appomattox," and to Major C. K. Henderson, who won his laurels under Carolina's courtly Kershaw. For that of Jenkin's Brigade to the gallant Gen Asbury Coward, the close friend and follower of the gallant Jenkins. '

For that of the 10th and 19th South Carolina I state what I saw myself, and my statements have been endorsed by many of the gallant men with whom I had the honor to serve.

To all who have helped I owe my deep obligations and beg to thank them most graciously and earnestly. Without their kindly assistance I would not be able to portray—thus truthfully I believe—the part taken by the various South Carolina troops in the grand historic events which this park and this monument commemorate.

I will not attempt to tell the general movements of the armies, or the gallant bearing of the thousands who made the glories of the historic spot. I will ask your attention only to the history of the sons of South Carolina, in whose honor a devoted and appreciative mother dedicates to-day her testimonial to their valor and to their worth. I could render but the feeblest justice in any words I could possibly use to the valor of those noble men of Carolina who have helped to make this (13) field so illustrious. It would be a glorious privilege to pay tribute to each and every son of South Carolina who gave his life on this field. Official reports and history record the glory of the leaders who fell, but only the weeping mother, the sorrowing wife or the faithful comrade preserve the name—engraved on their heart —or the humble private, who gave his life for the country he loved. The general who led and commanded, and the man behind the gun each did equal service. Each showed equal gallantry. When both died, battling with immortal valor, no one deserves encomium more than the other. I cannot, therefore, attempt to pay my loving tribute to the memory of any one son of our State.

"Yon marble minstrel "s voiceless stone

In deathless song shall tell,

When many a vanished age has flown,

The story how ye fell;

Nor wreck, nor change, nor winter's blight,

Nor time's remorseless doom,

Shall dim one ray of glory's light.

That gilds your deathless tomb."

I shall endeavor to give only a brief sketch of the movements on the battlefields covered by the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Park, of each of the commands of South Carolinians, as there were some who arrived too late to take part in the struggle at Chickamauga; yet they covered themselves with equal glory around Chattanooga. Justice also demandsthat [sic] Jenkins's gallant men should receive equal notice with those who battled at Chickamauga and Chattanooga.

Would that I had the time, the ability and the eloquence to do full justice to these grand heroes of this historic battlefield.

As we pass from the right, down that splendid line of bristling Confederate bayonets, in the hands of the incomparable men waiting eager and ready for the opening of the battle of September 20, the first South Carolinians were the brave men of the 24th South Carolina regiment, commanded by that gallant leader, Col. C H. Stevens, who, as brigadier general, gave his life to his cause in front of Atlanta.

Their being at all on this fated field illustrates the persevering devotion, overcoming all obstacles, with which the Confederate soldier always pushed forward towards the firing of the guns and the roar of the battle.

Gist's brigade of which the 24th South Carolina regiment was a part—and a most important part—had been sent to Rome, Ga., to ward off the threatened movement against Bragg's left, September 18 they were ordered up to (14) Chickamauga. At Kingston they were delayed as the one railroad was choked by Longstreet's Corps, from the Army of Northern Virginia, being rushed to the front. They would have been fully justified in waiting their movement by the railroad authorities. But the delay, which kept them from action, could not be tolerated by the spirit which inspired these noble men.

The particulars of the tremendous endeavors they made to reach the field have been kindly given me by Gen. Capers as follows: "About dark Col. Stevens grew very impatient at the delay and we were told that Longstreet's corps had all passed. Our cars were standing on the siding and we saw that the fires were out on our engine. Finally Col. Stevens determined to take the responsibility of going ahead, but we could not find the engineer. He, Col. Colquitt, (who yielded up his life the next day) and myself set out to look him up and found him asleep in a house and roused him up. He said he had had no sleep or rest for days and could not run his engine; said it was out of order, etc. Col. Stevens drew his pistol, but that did not move him, and then he told him that he would put a man on the engine to run it, and men to fire it, and when it was ready if he did not come and take charge he would kill him. The poor fellow said he would not and could not undertake the responsibility of the lives of the soldiers in his exhausted state. Col Stevens put a railroad man (I think from Company A. 24th South Carolina regiment) in charge of the engine, we fired her up and when we were ready to start, were forced the engine to take the direction of the crew we furnished, and we got off, carrying the 24th South Carolina regiment, part of the 46th Georgia regiment and the 8th Georgia Battalion."

To run the short distance to Catoosa Woodshed took until 10 o'clock the next morning, now made in about one hour. There the regiment waited for the rest of the brigade to come up and waited in vain. In sound of the guns from the battlefield they could wait no longer, so about 4 o'clolk [sic] in the afternoon moved forward to cross the Chickamauga at Alexander's bridge. The march was impeded all night by the ordnance wagons under their charge, which were being carried to the front. After marching all night and having passed "two terrible nights and a day never to be forgotten," worn, hungry, exhausted, they reached the battlefield about sunrise. By 11 o'clock these brave, but weary, men were in the storm of battle. This galling effort to reach the battlefield was exceeded by the sacrifices made and valor shown when charging (15) the "Bloody Angle." King's brigade of the United States regulars, occupied the bloody angle. This fatal spot was toward the left of the Union line, east of the Lafayette road on Kelly's farm, opposite the Kelly house. The line was sharply refused and run west at about right angles to the general line. The position was on the crest of the hill, with the ground sloping off gently to the Confederate lines. It had been fortified with felled trees, rails, etc, making a strong breastwork. Helm's brigade made three gallant, charges, but were repulsed. Gist's small, but heroic brigade, only about nine hundred strong, was then sent to attack the point.

The tweny-fourth [sic] South Carolina regiment was on the left of the brigade, which struck just to the north of the re-entering angle. With terrific effect the enfilading fire of the enemy carried death down the lines. The Twenty-fourth, from its position, caught the brunt of the storm of battle. The regiment changed front to conform to the line of the Union breastworks and gallantly charged on them. But the fire was more than man could stand, no progress could be made, so Gen. Gist was forced to withdraw the troops.

At about 5 o'clock P. M. the gallant boys again moved forward, with the advance of the entire right of the army, driving on victoriously until night closed over the field of strife. That the regiment lost all of its field officers wounded, its adjutant killed, and 169 out of less than 400 carried into the fight, and was finally commanded by a captain, Capt. D. F. Hill, attests the severity of the day's battle and the undaunted courage of its men.

Though this magnificent fighting on the enemy's left failed in any direct result to the Confederates, yet it contributed much to the success of the day. This attack forced the enemy to move at least three divisions from his centre and right, and thus weakened his right and opened the way for the successful assault of the Confederate left wing.

The 24th South Carolina regiment and the 16th South Carolina regiment, which had rejoined the brigade, took part in the movements around Chattanooga which followed, and finally—in the battle of Missionary Ridge, where they were on the right again. They were a part of the force which successfully defended Tunnel Hill against the attack of Sherman and did it with the most determined courage. They took part with Stevenson's and Gist's divisions in that glorious charge, which drove the enemy into the valley, capturing eight stands of colors and five hundred prisoners.

After the left of the army had been driven away they were (16) in the line formed across Missionary Ridge and checked the advance of the enemy. When retired they were in the rear guard, protecting Bragg's retreat, and in the final struggle at Ringold checked the advancing enemy.

Ringold! The Alpha and Omega of Bragg's career as a great Confederate leader. On his advance in the Kentucky campaign, soon after he took command of the army and when he carried the Confederate arms victoriously to the banks of the Ohio, Ringold, Ga., was the first point at which he met the enemy. After the disaster of Missionary Ridge it was the last point where the army he commanded met and checked the enemy. His career ended on the very spot where he commenced. He was the only Confederate general, commanding a large army, who never lost a foot of Confederate territory, but what he had previously taken from the enemy.

Attached to McNair's brigade, Johnson's division, of the noble men who had so long upheld the glory and success of the Confederate arms on the battlefields of Virginia, was Culpepper's battery. This was the only South Carolina battery which was on the field of Chickamauga. They had reached the battlefield early and participated in the battles of the 18th and 19th, following the movements of their brigade and doing valuable service. On the morning of the 20th of September they took part in the repulse of an attack on McNair's brigade at 9 :30 A. M. The field of Chickamauga was not one which gave much scope for the employment of artillery. Many batteries did not fire a shot.

When the general advance took place, about 11 o'clock, Gen. Law placed the guns of Culpepper's battery in position with his guns, two guns on the Poe field, about 75 yards north of the spot on which stands the magnificent testimonial erected by Georgia to her gallant sons. The other two guns were west of the Lafayette road, near the Brotherton house. The guns were handsomely served and thundered forth against the ranks of the enemy. The victorious rush of the Confederates carried the battle far from the position assigned the battery, and as they could not be used on the hilly ground over which their brigade was fighting, they were retained in their position and lost the opportunity of further participating in the events which crowned the Confederate arms with victory.

After the battle they were moved up to Chattanooga, but, being sent off with Longstreet to East Tennessee, they did not participate in the battle of Missionary Ridge.

Kershaw's brigade of gallant South Carolinians, of the army of Northern Virginia, who had covered themselves with (17) imperishable renown on many a field, were brought up, a part of Hood's division. They reached the battlefield during the night of September 19, crossing at Alexander's bridge. In the formation of the morning of the 20th they were in reserve and in rear of McLaw's division in the wooded country east of the Lafayette road.

At about 11 A. M. they promptly responded to the command, "Forward," and crossed the Lafayette road, near the Brotherton house. The order of formation of the regiments, all South Carolinians, from right to left was 8th, 15th, 7th, 3d, James' battalion, 2nd. They entered the Dyer field, which stretches out to our east, but soon changed front to the right, to conform to the enemy's line. The wheel was made on the 3d South Carolina regiment. The enemy were in strong position, at the foot of, and on the heights of, the very hill on which the South Carolina monument is placed. The gallant boys move forward with a cheer, are met with a deadly fire, but driving the enemy before them, passing over the very ground on which we now stand, and sweep on to the foot of Snodgrass Hill. This spot for the South Carolina monument was selected because it has been hallowed by the blood of South Carolina.

In making this movement the 8th South Carolina regiment obliqued [sic] so far to right, but always towards the enemy, as to leave a gap, which was filled by Humphrey's brigade. A further gap was made between the 7th and 15th South Carolina regiments, which was filled by the 15th Alabama regiment, Col. Oates.

At 3 o'clock Kershaw's clarion voice calls out the advance and his devoted command press forward to the attack of the enemy in their breastwork on the crest of Snodgrass Hill. But repeated attacks were as fruitless as those against all other parts of the enemy's lines, where he stood as the Rock of Gibraltar. Nothing discouraged, with ranks decimated, with ammunition almost exhausted, they kept up the fight. Gen. Longstreet, referring to this in his report, says: "Kershaw made a most handsome attack on the heights at the Snodgrass house.”

At 4:30 the 8th, 15th and 2nd South Carolina regiments, the other regiments of Kershaw being out of ammunition and held in reserve, with McNair's brigade and Preston's division, made a most determined attack on the enemy. Gen. Kershaw says of this attack; "This was one of the heaviest attacks of the war on a single point. The brigades went in in magnificent order. Gen. Gracie, under my own eye, led his brigade, now for the first time under fire, most gallantly and (18) efficiently. For more than an hour and a half the struggle continued with unabated fury. It terminated at sunset, the 2nd South Carolina being among the last to retire."

That night they bivouacked on the field of glory and the next day moved up to Chattanooga. They were engaged at various points about Chattanooga, but as they went with Longstreet to East Tennessee, they had no part in the battle of Missionary Ridge. Far over to the left of the Confederate lines, the good name and high reputation of South Carolina was nobly maintained by the 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment. This regiment formed the right of Manigault's brigade, Hindman's division. The two regiments having in their previous campaigns been reduced in numbers were consolidated into one, under the leadership of the gallant Col. James F. Pressley.

The regiment participated in the preliminary manoeuvres [sic] which led up to the battle of Chickamauga. On September 18, with their brigade, they were in an open field south of Chickamauga River, near Lee and Gordon's mill, taking part in the feint for a proposed crossing at that point —while Bragg made his true crossing to the right, further down the river. Some little firing took place —enough to make the position uncomfortable.

On the afternoon of the next day, September 19, they were moved across the river at Hunt's Ford, debouching on the battlefield and relieving some of Longstreet's troops. How envious we were of the fresh, new, natty uniforms of our comrades from Virginia. We did not know that a Confederate soldier could be dressed so well. Their neat gray uniforms were in sad contrast with our worn, varied, shabby homespun clothing. But, thank God, equally brave hearts, devoted to their cause and their country, beat under their jackets of gray and our homespun suits.

The line was formed in the wooded country about half a mile to the east of the Lafayette road They had no part in the active fighting of that day.

The momentous morn of September 20, 1863, broke fair and found everything ready for the attack, which had been ordered for daylight, commencing on the right. They waited patiently and only were ordered forward about 1 1 o'clock. The Lafayette road was crossed between the Vineyard and Brotherton house, and the 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment struck a patch of woods which have since been cut away, the left regiments of the brigade advancing through the open field leading up to the Widow Glenn's house (19).

The 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment moved steadily forward, struck the enemy's line, were received with a terrific welcome, but pushed their opponents back, and with Deas' and Anderson's Brigades of the Division pressed onward. They passed to the right of the "Bloody Pond," and the blood of South Carolina's sons in part gives it its fearful name. Driving the enemy across the Crawfish Spring road and to the crest of the hills to the west of the present railroad, and only halted when ordered to do so. They had driven the enemy about one mile. They were recalled and rejoined the brigade on the Crawfish Spring road.

Now they were moved to the scene of the most magnificent valor of this bloody fight. Excuse me—as to the events which follow I speak as an eye witness, interested and disinterested in the regiment. I was at that time Adjutant General of the brigade and so not a member of the regiment. But I had entered service as the adjutant of the 10th South Carolina regiment, subsequently was its lieutenant-colonel, and surrendered as commander of the two regiments again consolidated. That afternoon I was with the regiment almost uninterruptedly during its fight on Snodgrass Hill.

On Snodgrass Hill the regiment formed the extreme left of the Confederate battle. A brigade and the left regiments of our brigade went in on their left, but, having failed in their attack, left the gallant South Carolinians on the extreme left.

They were formed at the foot of a spur of the range, near the Vittetoe house, and moved up to the crest of the ridge. Dent's battery—a tower of strength—was on the line of the regiment during the whole afternoon. The enemy's line was some distance back on the range, with a battery in their line. As you came up from Lytle Station you saw, near the Vittetoe house, the tablet marking where the 10th and 19th South Carolina regiments, of Manigault's brigade, went up, and on the crest of the range is a battery, marking the position of Dent's battery, and this was the base line of the position from which the regiment advanced. The marker, which the State has erected, is considerably in advance, marking the spot of the furthest advance in the afternoon's battle.

At 3 o'clock in the afternoon of September 20 the order for assault was given and cheerfully and valorously responded to. The gallant Carolinians charged the enemy, but were driven back and were followed by the equally gallant men of Illinois and Ohio, of Mitchell's brigade, Sherman's division, until Dent's guns were unmasked and their fire checked the enemy. The Carolinians rally, turn, drive back their opponents, until (20) the guns of Battery M, 1st Illinois light artillery open, and in turn, forced them back. The whole afternoon was a repetition of such movements, each side backward and forward, with the most determined bravery and persistence, until as the sun set the enemy retired and left the Confederates in possession of the field. This fight was to the left of Gen. Bushrod Johnson's and the 10th and 19th South Carolina regiments—not, however, under Colonel Reed, as stated in his report were the two regiments which General Johnson says "participated in the invincible spirit which fired our men and continued to fight with us."

The fierceness and effectiveness of the fire at this point was shown by the large trees which were cut down by minie balls.

The firing having ceased in the front, the regiment was moved forward to rind the enemy, but he had gone, and it bivouacked for the night about half a mile in advance, on the east slope of the range, overlooking the Kelly field, and rested on a well earned and splendid victory.

The army moved up to Chattanooga and invested the city' staying there until the battle of Missionary Ridge, or Chattanooga.

At Missionary Ridge, at least in that part of the line defended by Hindman's division, the main line of the works was at the crest of the ridge, with an advanced line in the valley at its foot. The 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment was about opposite Orchard Knob. In this line, at the foot of the ridge, the 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment was placed with positive and clear instructions to retire to the line at the crest as soon as the enemy made an advance in force. When this came the men tiringly and under a heavy fire, wearily dragged themselves up to the works at the crest. The position of Deas's brigade was on the hill, near the present DeLong Tower. The 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment was just to its left, its right resting on the hollow between that hill and the one occupied by Manigault. The breast- works of Manigault's brigade had been placed so far to the front that from them the men could sweep the entire slope of the ridge. No enemy came up the ridge in its front.

It was a magnificent sight from the top of the ridge to see the enemy moving out in splendid order. The plain was open and all could be seen. It really seemed as if the whole plain had been covered with a blue veil. It was not to be wondered at, a remark which was made. A gallant fellow, looking at the vast hosts of the enemy steadily advancing, said that he was willing to fight the Yankees two to one, or three to one, (21) and he would risk four to one, but when he heard old Grant standing on Orchard Knob call out, "Attention World; by Nations, right and left wheel." he really thought he could with great propriety retire. But with all these mighty hosts advancing and pressing on, that soldier did not retire until his officers told him to do so.

The brigade on the left of Manigault is driven from its works and the enemy press his left and threaten to envelop it. The brigade on his right then gives way and the enemy threaten to surround him, also on the right. General Manigault gives the order to retire. The 10th and 19th South Carolina regiment barely escape capture from the enemy on their right. They reluctantly abandoned a position which, so far as a front attack was concerned, had proved impregnable.

The gallant South Carolinians were not driven out of their first line, only retiring as ordered. They were not driven from the line at the crest. No enemy ever came up that ridge in the front and only threatened capture from the enemy, who broke the Confederates on the right and on the left, caused them to be withdrawn—under orders and necessity. So far as the foe in their front was pushing them, they could have been there today.

At the east foot of the ridge they formed a line, but the enemy advancing no further, after dark they were quietly withdrawn across the Chickamauga River.

The gallant men of Jenkins's brigade, consisting of the Palmetto Sharpshooters, Hampton Legion, 1st 2nd, 5th and 6th South Carolina regiments, who had won imperishable renown in the Army of Northern Virginia, arrived too late to take part in the struggle at Chickamauga. And this brigade was sent off with Longstreet to East Tennessee before the battles around Chattanooga. So they took no part in the two great battles which this park commemorates. They were, however, engaged in the night fight, October 28, 1863, in the Wauhatchie Valley, under the leadership of the fearless and skilful [sic] Bratton. The enemy had secured Brown's Ferry, opening the road for the relief of Chattanooga, and a portion of Hooker's corps, making its way from Bridgeport toward that point, went into camp for the night near Wauhatchie. It was determined to cut off this party by a night attack.

Jenkins's brigade acted with its accustomed gallantry, but the odds were against the movement and it failed of the hoped for results. In that fight many a brave South Carolinian gave his life for his cause, drenching with his blood the soil of Tennessee. The loss of the brigade was 356 and of this loss (22) 113—about one-third—fell on one-sixth of the command of the noble 5th South Carolina regiment, led by the intrepid Asbury Coward.

If Confederate gallantry could have saved that fight Jenkins's noble men would have done it and added lustre to the Confederate arms, and made a success that which was otherwise doomed to a failure.

I have thus briefly sketched the movements of the South Carolinians who on this great battlefield so nobly upheld the honor of their State. The sons of nearly every State, North and South, achieved on this field a heritage as glorious for each of their mothers. There were thousands of acts of heroism as brilliant as those I have recited. This park then surely marks one of the most historic spots in our broad country. Where we are now gathered was won the glorious Confederate victory of Chickamauga. In this park and almost within sight of us now, was achieved the Union victory of Chattanooga. Combats which made the very earth shake with the conflict of arms and heavens weep over the moans of the dying.

No place in our country could by more appropriately consecrated to the unparalleled valor of the American soldier. It was the only ground where, in that tremendous conflict, each side won a signal and decisive victory, under almost similar conditions and with like results. In each the attacking party advanced and fought first over level country, and made their final struggle on the hill tops of Snodgrass Hill or Missionary Ridge. In each battle a decided and unquestioned victory was won. After each the victor was so exhausted by his efforts that he did not again quickly strike his beaten enemy. Here then, on this spot, consecrated by equal valor and similar victory, can we all meet.

The design to consecrate this park to the valor of the Confederate and Union soldier — together, the American soldier — whose glory is the common heritage of our country, was conceived in a most liberal spirit and has been carried out with even greater liberality.

On every tablet and mark placed by the commission on this battlefield, in every attention given to the visiting Veteran, the utmost impartiality has been shown. Well have those who have been charged with the arrangements and government of the park carried out the catholic intention of those who conceived and planned this magnificent tribute to American—not sectional —valor. To the broad minds of Generals Ferd, Van Derveer and Henry V Boynton do we owe the conception of the idea. To their indomitable energy, assisted (23) by many Union and Confederate Veterans and statesmen, we owe the accomplishment of their plan for this great national park.

In addressing the first meeting to inaugurate the movement General Boynton said that, when riding over the battlefield in the summer of 1888, with General Van Derveer, "there rolled back on the mind the unequalled fighting of that thin and contracted line of heroes, and the magnificent Confederate assaults which swept in upon us time and again and ceaselessly, and that service of all the gods of war went on throughout those Sabbath hours.

Then thinking of our Union lines alone—we said to each other: "This field should be a Western Gettysburg—a Chickamauga memorial."

It was but a flash forward in thought to the present plan and the proposition became, "Aye, it should be more than Gettysburg with its monuments along one side alone; the lines of both armies should be equally marked."

General Boynton further says: "I stood silent thinking of that unsurpassed Confederate fighting, and my heart thanked God that the men who were equal to such endeavors on the battlefield were Americans. Let all lines be marked —let the whole unbroken history of such a field be carefully preserved."

Thus in the very birth of the scheme was breathed justice to all. The originators further announced, endorsing the grand and liberal sentiments of General Boynton. "There was no more magnificent fighting during the war than both armies did here. Both sides might well unite in preserving the field where both, in a military sense, won such renown." Wonderfully has this forecast been fulfilled. In the very formation of the commission a place was given to a distinguished Confederate General, our own dearly beloved Stewart, and thus was shown the broad spirit designed.

Without detracting one iota from the credit due to all who have been members of the commission, permit me further to say, and all veterans who have visited the field will, I know, endorse me, that the magnificent results obtained here are chiefly due to the courtesy, the patience, the noble persistence and thorough impartiality of the present chairman of the commission, Gen. Henry V. Boynton.

This is one of the places owned and controlled by the United States Government, linked to the memory of great Confederate struggles, where we good old Confederates are made to feel that we are entirely at home. That we have a right to be (24) here. That we have a perfect right to erect a monument to the valor of South Carolina's Confederate soldiery by the very side of one to the gallant men who upheld the Stars and Stripes.

Brother Confederate Veterans, you will see on this battlefield what none of us, as we went sadly home in 1865, ever dreamed of seeing. Witness the splendid monuments to our fallen Confederate brigade commanders, erected by the United States Government. And when you look at similar monuments to the fallen Union Generals you will find not a particle of difference. The Confederate and Union hero has been treated alike.

It is a grand privilege to live under a free and liberal government, which within a brief space of the close of the most gigantic and bitter struggle, does honor to its former enemies. It has invited us, but a short time since fighting against it, to consecrate in a park, by it founded and controlled, the monument which we today dedicate—to the worth and valor of those who were not long since its enemies. Comrades, why can this be? It is possible because your forefathers and theirs planted deep in the hearts of the people of this country, which they founded and nourished, a love of justice, liberality and freedom. It is because the splendid heroism you showed on this and a hundred other battlefields has won the admiration of your fellow-citizens, aye, of the whole world.

I stand on this sacred spot, under the very folds of the Star Spangled Banner, in the presence of the representatives of our great Government—standing thus, I say that I am proud that I was a Confederate soldier—I am proud that I was one of those who helped make the Confederate glories of Chickamauga. Feeling thus, I thank God, that the time has come when I can, with such surroundings, say this, without my loyalty to the United States being questioned, nor my faithfulness to the glorious past of the Confederacy being doubted.

May the lessons learned here today make us all better and, if such be possible, truer citizens of our great country, which here honors the Confederate soldier.

All was not lost at Appomattox or at Greensboro. The Confederate soldier acknowledged his defeat like a man. And when peace again spread its wings over our fair land his best talents, energy and industry were devoted to the upbuilding of the land he loved. Grand as was the struggle of the Confederacy, a thousand times grander was the struggle of her sons, in peace and loyalty to rebuild their ruined firesides, reconstruct the social life which had been shattered, make their families once more happy, and this, their country, the home (25) of freedom, liberty and prosperity. Our immortal Lee said that the sublimest [sic] word in the English language was "duty". As the old Confederate did his whole duty to the Confederacy, he has done his full duty to the United States.

We Confederates from 1861-65 followed Lee amid the storms of battle. We have faithfully carried out his noble admonition, expressed in 1865: "It is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the country, to do all in his power to aid in the restoration of peace and harmony." That you, my brave comrades, have honestly and successfully done this is evidenced by this day's proceedings.

There stands no truer indication of the peace you have maintained nor the harmony you have cultivated than the fact that I can, and that I am willing, to pay this tribute to the Confederate dead and the heroism of the gallant sons of Carolina under the protection and under the very folds of the flag which we then strove to pull down. The monument which South Carolina erected and today unveils stands an immortal tribute, not only to the valor of her sons who fought on this historic battlefield, but to the peace and harmony which now blesses our land.

"There's a grandeur in graves — there's a glory in gloom;

For out of the gloom future brightness is born.

As after the night, looms the sunrise of morn;

And the graves of the dead, with the grass overgrown,

May yet form the footstool of Liberty's throne;

And each single wreck in the warpath of Might

Shall yet be a rock in the Temple of Right."

Click here for the full text of ceremonies.