James Barrett

The British targeted James Barrett’s home on April 19, 1775, believing it was the location near Concord, Massachusetts where colonial militia stored cannons and gunpowder. The Redcoats did not find what they were looking for that day, but Barrett’s role as a community leader and militia officer helped to spark the Revolution that changed America and the world.

Born on July 31, 1710, James Barrett grew up in Concord. His father, Benjamin Barrett, owned a farm and built the family’s wooden farmhouse in 1705. During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), James Barrett served as a captain, and when he returned to his hometown, he took an active role in local politics. He represented Concord in the Massachusetts General Court beginning in 1768 and in the Provincial Congress starting in 1774, receiving re-election for these legislative assemblies each year until 1777. With his previous military experience and growing community leadership, Barrett become a commissioned colonel, commanding the Middlesex Militia Regiment.

The Provincial Congress ordered Colonel Barrett to gather and protect the colony’s military supplies near Concord, including four cannons which had been removed from Boston. Barrett divided the weapons and gunpowder between thirty farms in the vicinity of Concord for storage and concealment. The British believed that Barrett hid the cannons on his own farm or nearby mill.

At the Barrett Farm, the colonel lived with his wife, Rebeckah, and three of their unmarried children, two sons and a daughter. A young enslaved man named Phillip also lived at the Barrett’s in April 1775. Through a network of informants and midnight messengers word reached Concord in the early morning of April 19 that a British force had left Boston and was known to be heading for Concord to seize the cannons and other military supplies. Anticipating this, Barrett had already moved the cannons to Groton, a village nearly twenty miles away. He and the other farmers made sure the other military supplies were hidden. Barrett used pine boughs and garden furrows to conceal the supplies that remained on his property and left a few old gun carriages in his barn.

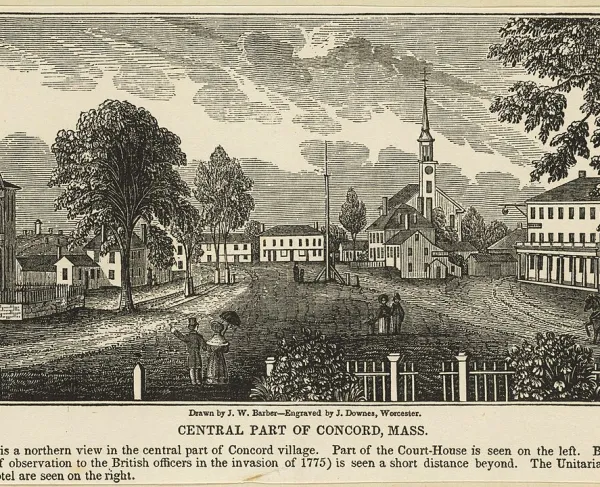

On April 19, 1775, approximately 700 British troops arrived in Concord. They had already met resistance from local militia at Lexington during their march and shots had been fired. Colonel Smith, commanding the British expedition, sent about 120 soldiers the additional two miles from the village of Concord to Barrett’s farm. Colonel Barrett was not there, having already joined the gathering militia companies. Mrs. Barrett met the British soldiers, told them they would not find military supplies on the farm, but gave them permission to search. The Redcoats found the old gun carriages but no cannon, and they missed the concealed supplies in the field furrows. Meanwhile, several officers asked Mrs. Barrett to make breakfast. She gave them food and refused pay, quoting her religious conviction to feed an enemy if he is hungry.

While the detachment of British soldiers searched Barrett’s farm and talked with Mrs. Barrett, the colonel and other militia officers moved to Old North Bridge, leaving the village in British hands for the moment. Eyewitnesses remembered that Colonel Barrett wore a leather miller’s apron over his worn clothing and carried a naval cutlass as he led the assembled farmers, innkeepers and tradesmen. He kept order and told the militiamen not to fire unless the British shot first.

Finding few supplies in Concord, more British soldiers were sent toward Old North Bridge and the Barrett Farm to join the contingent that had already been ordered there. However, this time Barrett and the other American officers opposed the British movements. Shots were fired at the bridge, and the British fell back. The sent-out groups of British soldiers rejoined their main body in Concord, and the expedition headed back toward Lexington and Boston, facing ambushes and fighting along the way.

James Barrett’s farm and leadership were at the center of fateful events in April 1775 as the American Revolution began. But he died before the end of the war, passing away on April 11, 1779. In 2003, Barrett’s farmhouse was purchased and preserved by Save Our Heritage, and as of 2012, the historic home is protected within Minuteman National Park.

Related Battles

93

300