The Monroe Doctrine

One of George Washington’s final messages to Congress during his presidency involved a warning to avoid “entangling alliances” with the Europeans powers, which provided an important precedent for early American foreign policy going forward. But strict isolationism was always impossible of course, due to America’s mercantile interests in Europe, and the drastically shifting political landscape of the early 19th century was impossible for anyone to ignore. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars and the restoration of the French Monarchy, both Europe and the Americas stood at a crossroads. In a grand attempt to turn back the clock and permanently suppress republicanism, liberalism and all other forms of revolutionary politics, diplomats representing most of the great powers of Europe formed the Congress of Vienna. But while the effects of the French Revolution had been temporarily suppressed in Europe, the splash it made rippled across the world, triggering a series of independence and republican movements across the former Spanish colonies of Latin America. As the European powers struggled to defeat figures such as Simon Bolivar in South America, many Americans worried that if their Southern neighbors succumbed to repression and imperialism again, the same might happen to the United States? Bourbon France, too, sought to reestablish a colonial presence in the New World in Spain’s absence, and openly discussed converting the colonies into small puppet kingdoms, each ruled by a Bourbon relative.

The next moves by the European powers seemed to confirm their fears. After the Battle of Waterloo, the Monarchs of Prussia, Austria and Russia formed their so-called “Holy League,” symbolically uniting their three state denominations of Protestantism, Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy respectively against further republican or nationalist uprisings. Even more worrying, by the 1820’s, reports reached Washington D.C. about Russian expeditions reaching further south and inland of the Pacific Coast of North America. Though very little of this land was settled with Europeans, both Britain and America had designs on the region, and both were outraged when Russia unilaterally issued the Ukase (proclamation) of 1821, claiming sovereignty over the entire Pacific Northwest.

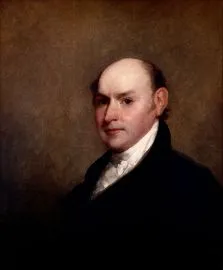

To prevent any unnecessary conflict in what they saw as a hopeless dream, Great Britain came to President James Monroe with an offer of a multi-lateral agreement to keep France and the other powers away from South America. While tempting, Secretary of State John Quincey Adams advised against aligning too closely with Britain. Adams argued that going along with the scheme would have made the United States a junior partner in affairs that directly affected its interests, “a cock-boat in the wake of a British man-of-war,” as he put it. This was especially dangerous when the two nations still had competing interests in North America. Instead, he advised Monroe, the United States must make a unilateral declaration of primacy in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere, pledging to oppose all future attempts by Europeans to recolonize North or South America and pledging neutrality in European affairs in return. That way, he might deal with the Spanish, French and Russian threats all at once. Monroe proceeded to do just that, laying out these principles first in a message sent to the British Secretary of State George Canning, and then to Congress in the equivalent of our modern State of the Union address. “With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere,” Monroe acknowledged to maintain America’s neutrality, “But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.” And so, the later-named Monroe Doctrine was born. International reaction was swift but divided. Austrian diplomat Prince Klemens von Metternich, the architect of the Vienna Congress, accused the United States of insubordination, while Britain calmly accepted the change in policy, content with preserving neutrality on the high seas. Reaction in Latin America was also not universal. Many leaders of the various independence revolts appreciated the United States’ support, while others took the realistic view that it currently had no ability to project its authority across the entire hemisphere. A few actually voiced concerns over the Doctrine, such as Chilean politician Diego Portales who wrote, “For the Americans of the north, the only Americans are themselves.”

Ever the diplomatic and political center of Europe, or so it saw itself despite its recent humbling, France took absolutely no account of the Monroe Doctrine in shaping its foreign policy, as it had no backing in international law, or indeed anything other than the threat of force. This attitude continued even as the clash of dynastic and revolutionary politics continued to shake France domestically for the next few decades. It did however, issue the first major challenge on the matter when Emperor Napoleon III decided to intervene in Mexico. In a scheme based, as historian Frederic Bancroft argued, more on grandeur than sense, Napoleon’s plan to intervene in the chaotic political landscape of Mexico began as a means to rectify the damage done to French business interests and visitors by the instability and evolved into one to improve France’s relations with Austria and the Papacy after the recent Italian wars and reestablish a new French Empire in the Americas. French troops landed in Mexico in 1862 with the coordination of several prominent Mexican conservative Catholics, forced to the margins by the anti-clerical liberals of Benito Juarez’s government. By the spring of 1863, France had taken Mexico City, sent Juarez into exile, abolished the Republic and installed Maximillian von Habsburg, brother of Austrian Emperor Franz Josef, as its puppet ruler.

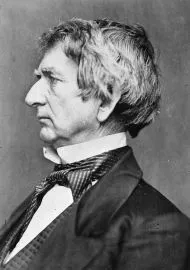

The invasion and overthrow of a republican government just south of its border outraged Washington, but both President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward saw the futility of antagonizing France while dealing with their own civil war still raging, especially with the chance of Napoleon giving the Confederacy diplomatic recognition in exchange for protecting Maximillian. In fact, Lincoln and Seward went out of their way to quiet any Senators or Congressmen who did publicly voice opposition to the intervention, so delicate was the situation. Throughout both countries’ civil wars, however, Washington continued to recognize Juarez as the legitimate Mexican head of state, and after defeating the Confederacy, the federal government’s policy of strict neutrality began to drop. Seward and President Andrew Johnson decided not to go to war directly, but invoking the Monroe doctrine, instead sent an army under General Philip Sheridan to the southern border in Texas. Officially, he was tasked with removing any Confederate holdouts in the region, but once pacified, Sheridan continued to occupy the area and leave weapons, munitions, and other supplies at designated drop points for Juarez’s rebels, who still managed to hold out this entire time, to pick up. Sheridan and his troops ended up smuggling over 30,000 muskets alone through the border, which helped give the liberals the edge they needed to retake lost territory. As Juarez pushed further south, international pressure for France to abandon Mexico came down harder on Napoleon than ever before, and the last French troops left North America by 1866. One year later, the Juarez government returned to Mexico City and executed Emperor Maximillian by firing squad.

Though the Mexican Intervention ended in failure for France, it revealed an important truth about the Monroe Doctrine; namely that it was not a matter of international laws but of America’s willingness to enforce its position of primacy in the Western Hemisphere. Indeed, despite its intended effect on changing European behavior in the Americas, the greatest effect it had was on Americans themselves, and how it shaped the view of their place in the world. Historian Gretchen Murphy called it an act of mapping, “the political binary between Old World tyranny and New World democracy.” Eventually, later 19th century statesmen like Theodore Roosevelt would turn the idea of America as the guarantor of liberty in the Western Hemisphere on its head, using it to justify countless interventions in Latin America, Hawaii and other regions, beginning the age of America as a global power.