Attacked at Midnight

A month after the Battle of Chickamauga, help was on its way to the Union army besieged at Chattanooga. To stop this effort, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet launched a rare night attack aimed at a small Union force at Wauhatchie, Tennessee.

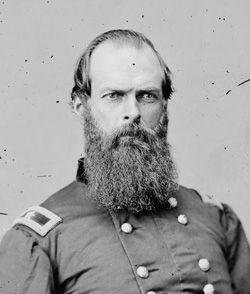

After a long day's march, 18 year-old Lieutenant Edward Geary and a few of his comrades from Knap's Pennsylvania Battery ventured into Nickajack Cave, a grotto in the Raccoon Mountains and something of a "curiosity" to the men of the Union Twelfth Corps camping near Shellmound, Tennessee. The cave had once been the site of an installation that was reportedly the Confederacy's chief source of saltpeter. That installation had since been abandoned, leaving Geary and his comrades to marvel at the cave's magnificent high ceiling and the crystal clear water that ran for miles underground. The young men were accompanied by Edward's father, their division commander, Brig. Gen. John W. Geary, who delighted in watching his son's face "enlivened with all the vivacy which the scene excited."

Geary and his son were part of a large movement of troops from the Army of the Potomac to the western theater. Following the Union defeat at Chickamauga in the autumn of 1863, the Army of the Cumberland was holed up in the city of Chattanooga, with the Confederate Army of Tennessee looking down on it from the heights south and east of the city. The Federal force was essentially cut off from the outside world and running out of rations. To help relieve the situation, the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps, under the joint command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, travelled by train to Nashville, then on foot through Alabama toward Chattanooga where they were to link up with troops of the Army of Cumberland who had established a bridgehead on the southern bank of the Tennessee River at Brown's Ferry. By October 27, the day Geary and his son made their excursion to Nickajack Cave, Hooker’s troops were within a day’s march of Chattanooga. If the connection could be made, supplies could flow into the city once more.

This movement did not go unnoticed by Confederate commander, Gen. Braxton Bragg. From their commanding position atop Lookout Mountain, Confederate signalmen watched the head of Hooker’s column march into Lookout Valley. By midday, elements of the Union Eleventh Corps had already linked up with troops from the Army of the Cumberland at Brown's Ferry, who were no doubt strengthening their position there with earthworks. Further south, however, a small Union rearguard was assembling along the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad at Wauhatchie. To remedy the situation, Bragg turned to Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, whose troops occupied the Confederate left flank. Longstreet determined to send John Bell Hood's division (now commanded by Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins) down into Lookout Valley, across Lookout Creek, and destroy or capture the Yankees at Wauhatchie. To surprise the Federals, the movement would begin after dark. If successful, the Confederates would block the new supply line and the Union forces in Chattanooga would continue to starve.

Arriving at Wauhatchie that afternoon, General Geary found a position that was hardly formidable. Wauhatchie itself was scarcely more than a crossroads with the railroad running north to south, roughly parallel to the wagon road the Federals had used during their approach. Another road veered off to the west, over Raccoon Mountain toward Kelley's Ferry. Apart from a large cultivated field at the crossroads, most of the surrounding area was heavily wooded. North of the field, a small tributary of Lookout Creek cut a westward path to a swamp on the clearing’s western edge. A small log house stood on a knoll on the southern end of the field, less than 100 yards west of the railroad.

Geary had fewer than 1,600 men and four pieces of artillery to guard this junction. Various regiments had been detached to guard the division's supply train and key points along the route. Worse, a shortage of trains prevented an entire brigade (Col. Charles Candy's) and most of the corps artillery from making the trip. Geary posted the four Parrott’s of Knap's battery on the knoll, where it commanded "all the cardinal points." He then put the 29th Pennsylvania on picket duty and had the rest of his men sleep with their cartridge boxes on.

Jenkins’ Confederate division crossed Lookout Creek after dark. Brig. Gen. Evander Law's Brigade took position on high ground overlooking Brown's Ferry. Together with Brig. Gen. Jerome Robertson's Texas Brigade, Law was to prevent the Yankees there from reinforcing Geary. Further south, Brig. Gen. Henry L. Benning's brigade of Georgians protected the bridge over Lookout Creek and would render aid if the situation took a turn for the worse. Responsibility for taking Wauhatchie rested on the shoulders of Col. John Bratton, commanding Jenkins' brigade of South Carolinians. With Law and Robertson protecting his rear, and Benning guarding his escape route, Bratton moved south along the railroad toward the Yankee rearguard.

The first cracks of rifle fire signaled Bratton’s approach at around 10:30 p.m. Geary, who thought the Eleventh Corps had cleared the valley north of his position, must have been surprised to hear firing from that direction. Within moments, steel ramrods began to clatter as the Yankees loaded their weapons for battle. George Collins of the 149th New York remembered the men loading with hands that trembled from the combination of the cold night air and the sudden nervous shock of the impending struggle. Seeing a “considerable commotion” in the Yankee camp, Bratton deployed his brigade in a wide arc. The Palmetto Sharpshooters moved east of the railroad embankment, hoping to get astride Geary's right flank. The 2nd, 1st, and 5th South Carolina then extended Bratton's line to the west. In the ensuing lull, Geary thought it must have been a false alarm. With their cartridge boxes still on and their rifles loaded, the men of Cobham's and Greene's brigades were again allowed to sleep. Col. David Ireland even permitted the men of 137th New York to take off their shoes.

Those that could didn't sleep long. The firing resumed at 12:30a.m. as Bratton launched his attack. Pickets of the 29th Pennsylvania kept Bratton at bay while Geary put the rest of his men into line. The 111th Pennsylvania anchored their right flank on the railroad. The 109th Pennsylvania formed on their left, both regiments in front of Knap's battery. The 149th and 78th New York of Brig. Gen. George S. Greene's brigade took position along the north-south axis of the railroad, using the embankment for protection and guarding the Union right. The Federals were not in position very long before a volley from the 2nd South Carolina lit up the clearing in front of the Pennsylvanians. A moment later, an officer on the knoll bellowed, "battery, fire!" The four guns of Knap's battery lent their weight to the midnight contest. With only the muzzle flashes of the enemy to guide them, the two sides blazed away in "point-blank business." The Pennsylvanians got the better of the contest in this sector, no doubt thanks to the help of the artillery. The 2nd South Carolina fell back in confusion.

Bratton fared a little better on his right where the 5th South Carolina was working its way through the swamp and around the Union flank. The butternut-clad soldiers could make out the forms of the Federal wagons parked in this vicinity and were no doubt excited at the prospect of capturing them. The men assigned to protect this flank, the 137th New York, were delayed in getting into position; the men needed to put their shoes back on. This done, the New Yorkers raced through the woods to the imperiled left and arrived in time to deliver a withering volley that slowed 5th South Carolina. Brig. Gen. Greene, then in the act of encouraging Col. Ireland's regiment, had a bullet plow through his face, badly breaking his upper jaw. Unable to speak—but still conscious—Greene turned command of his brigade over to Ireland.

"[A] splendid pyrotechnic display" illuminated the Federal position. Bratton could see that Geary's line had not broken—but it had bent. He called up the 6th South Carolina under Maj. John White to take the place of the battered 2nd South Carolina and press the attack against the Yankees' center. At the same time, Col. Martin Gary's Hampton Legion moved to the right to get around the 137th New York's left flank. The fire was so heavy that Gary's regiment could only get into position by crawling on all fours. Once they were in line, the South Carolinians rose up and advanced into a sheet of flame. The left two companies of the 137th New York had refused their flank. Joined by reformed pickets from the 29th Pennsylvania, these New Yorkers slugged it out with the Rebels in a deadly firefight that was racking up casualties by the score.

The center of the battlefield was equally deadly. Knap's battery was wreaking havoc in the Confederate ranks—but at a dreadful cost. Out of canister, the gunners began firing spherical case with the fuses cut short. The first of these shots exploded among the ranks of the Federal infantry, causing a number of casualties. Each blast of the Federal guns briefly illuminated the battery's exposed position on the knoll. Confederate officers told their men to aim for the gunners, an injunction the Rebels readily obeyed. Battery commander Capt. Charles Atwell went down with mortal wounds to the hip and spine. Lt. Edward Geary personally sighted a piece and had just given the order to fire when a bullet slammed into his head, killing him instantly.

Just when Bratton thought the situation "was entirely favorable to a grand charge," he received orders to withdraw. Law's brigade had fallen back from its position near Brown's Ferry and Union troops were on their way to reinforce Geary. Bratton ordered the 6th South Carolina to join the Palmetto Sharpshooters on the eastern side of the railroad and make a demonstration against Geary's right while the rest of the brigade withdrew. White's men advanced to the railroad where his men found themselves huddled against the embankment opposite the 111th Pennsylvania and the 149th New York. Both sides fired blindly at one another until Col. Rickards of the 111th Pennsylvania ordered his men to haul one of the guns of Knap's battery over the embankment. The Federals got a few rounds off on the Confederate flank before the they made their escape. After three hours of intense combat in the dead of night, the Battle of Wauhatchie was over.

It was nearly 5:30 a.m. on October 29 when men from the Eleventh Corps arrived at Wauhatchie. As the sun broke over Lookout Mountain, "the tall portly form of Gen. Geary" could be seen standing amidst the wreckage of Knap's battery. At his feet lay the lifeless body of his first-born son. "I have gained a great victory," the general wrote his wife, "[b]ut oh! how dear it has cost me. My dear beloved boy is the sacrifice [and] could I but recall him to life, the bubble of military of fame might be absorbed by those who wish it."

By the numbers, the Battle of Wauhatchie was a small affair. Bratton's brigade lost 356 men in their fight with Geary's division, the majority of them in the fighting on the Union left. The Federals, who brought fewer than 1,600 men into the fight, lost 216. Roughly half of those were in the 137th New York and Knap's Pennsylvania battery, which had been so thoroughly decimated that only two of its four pieces could be manned, and only after recruiting men from the infantry to replenish its ranks. Despite the small size of the engagement, the fighting on the night of October 28-29 had significant ramifications for the military situation around Chattanooga. The Confederates had missed their last best chance to prevent the Yankees from reinforcing Chattanooga. Supplies and men soon began flow through into and through Lookout Valley. A Federal resurgence in north Georgia was only a matter of time.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...