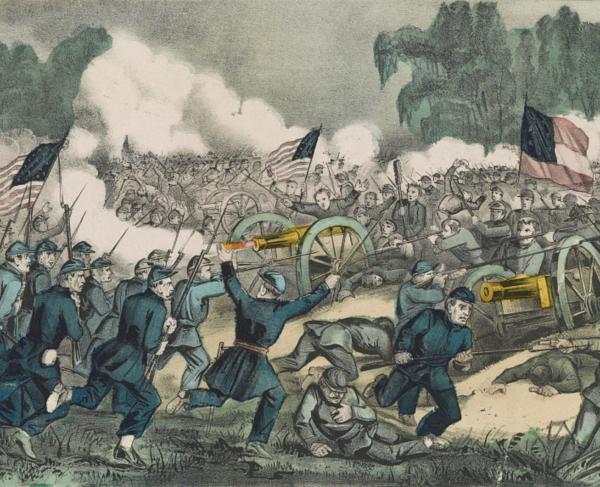

Antietam: Federal Flank Attack at Dunker Church

BY ROBERT CHEEKS

By mid-morning on September 17, 1862, the flower of the Union Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph Hooker’s I Corps, lay shattered in a sanguinary 40-acre cornfield immediately northeast of Sharpsburg, Maryland. The Federal assault on the Army of Northern Virginia’s left flank, planned en echelon, had floundered from the beginning. Major General Joseph Mansfield’s XII Corps came in late, not because the 59-year-old commander was notably slow, but because he had limited communication with both Hooker and the army commander, Major General George McClellan.

Mansfield had brought the 10,000 infantrymen of his command in on Hooker’s left and promptly spread his two divisions in a wide arc that covered part of Hooker’s line and extended well into the East Woods on his left. Brigadier General Alpheus Williams’ 1st Division penetrated the North Woods and came up on the rear of the I Corps. At the same time, Brig. Gen. George Greene’s 2nd Division became divided, with Colonel William B. Goodrich’s 3rd Brigade drifting to the right, toward the Hagerstown Pike. Greene’s remaining two brigades, commanded by Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale and Colonel Henry Stainrook, were ordered into the East Woods with the intention of moving in an oblique to the right and coming in on the Confederate flank that had driven Hooker’s corps out of the cornfield.

Tyndale’s 1st Brigade debouched from the woods and opened a galling fire on Colonel A.H. Colquitt’s Georgia brigade, which was holding behind a fence just below the North Woods. The Southerners were hit in flank and front at a range of less than 100 feet; the Confederate dead were described as ‘literally piled upon and across each other.’ The newly formed 28th Pennsylvania came out of the East Woods south of Tyndale’s brigade and caught the right flank of Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland’s brigade in an exposed position. Garland himself had been killed a few days earlier at South Mountain, and command had fallen to Colonel D.K. McRae. The new commander was having a difficult time with one of his regiments, the 5th North Carolina. The 5th was composed of large numbers of newly conscripted soldiers who had performed badly at South Mountain, skedaddling in their initial engagement. The brigade’s advance was ‘vacillating and unsteady,’ and the men were under a horrific cannonade. The line came to a sandstone outcropping that provided some cover.

Captain Thomas M. Garrett, commanding the 5th North Carolina, was informed that an enemy force was on his right, and accordingly he ordered his infantry to refuse their right and take cover behind some trees. Just then, Garrett later reported, Captain T.P. Thomson came running up to him, shouting: ‘They are flanking us! See, yonder’s a whole brigade!’ Thomson’s flagrant indiscretion destroyed what little morale remained in the regiment, and the soldiers began to break for the rear, despite the best efforts of their officers. The 28th Pennsylvania fired a coordinated volley with nearly 800 muskets and broke the spirit of Garland’s brigade and the heart of its commander. ‘The troops left the field in confusion,’ McRae reported, ‘the field officers, company officers, and myself bring up the rear.’

Farther north, at the edge of the cornfield, Tyndale’s Ohioans continued to exchange volleys with Colquitt’s Georgians. After a few minutes, the Federals locked bayonets onto their Enfield rifles and charged. The Georgians fought valiantly, as they always did. The 6th Georgia, 250 men strong when the morning began, brought a mere 24 soldiers out of the cornfield. The remainder of Colquitt’s regiments had been badly decimated as well, suffering 50 percent casualties and losing all their field officers. After a half-hour of fighting the Georgian troops could take no more and broke for the rear, followed closely by the wild-eyed Ohioans.

The 28th Pennsylvania took up the pursuit of Garland’s brigade while, farther south, Stainrook’s regiments entered the East Woods just above the Smoketown Road, driving recalcitrant elements of Brig. Gen. John B. Hood’s shattered division before them. The cornfield was cleared of all Confederates, but the Federals had lost Mansfield, the XII Corps commander, who had been mortally wounded minutes earlier in the East Woods. The Federal lines were in disarray. Greene’s two brigades were in a precarious situation. The general galloped out to the advanced position of the 102nd New York. ‘Halt, 102nd!’ he shouted. ‘You are bully boys but don’t go any farther! Halt where you are! I will have a battery here to help you.’ Greene had also learned about Tyndale’s desperate situation.

The 1st Brigade’s troops had fired off nearly all their ammunition in their fight with the Georgians and now found themselves in the field above the Mumma farm buildings, south of the Smoketown Road. Greene immediately sent for the XII Corps’ trains. He then galloped toward the East Woods, searching desperately for much-needed artillery.

There was now a brief reprieve in the battle. The artillery continued to bellow, but infantry assaults on both sides ceased for the time being as the combatants groped for fresh regiments to throw into the conflagration.

The ammunition wagons arrived, and Tyndale’s brigade was resupplied. The men moved to a slight elevation facing southwest in the Mumma swale and awaited the Rebels. Both Robert E. Lee and McClellan were busy funneling infantry into the West Woods. Lee transferred Maj. Gen. W.H.T. Walker’s division from the right and ordered Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ division, marching in from Crampton’s Gap, directly into the fray.

At about the same time, Union Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 2nd Division marched into the West Woods to meet its doom. Stainrook’s brigade came up on the left of Tyndale’s brigade and extended the Federal line southwest of Dunker church, just as the 2nd Division was being mauled by McLaws’ and Walker’s divisions. In advance of Tyndale’s line and just 50 yards west of the church, Captain J. Albert Monroe ordered his six 12-pounder Napoleons of Battery D, lst Rhode Island Light Artillery, to drop trail and fire on elements of Brig. Gen. J.B. Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade of Walker’s division, who were now making their appearance on the field south of Dunker church.

As the 8th, 7th and 3rd South Carolina regiments charged toward Greene’s division, the 7th Ohio, commanded by Major Orrin J. Crane, fell back below the rise, and the 5th Ohio, under Major John Collins, lay down on the grassy knoll. The South Carolinians came within 50 yards of their objective, but the massed Union forces and their artillery supports poured a series of brutally accurate volleys into the Confederate assault formations.

With their dead and wounded littering the open field, the South Carolina regiments withdrew into the woods. Kershaw ordered Captain John P.W. Read to move his two 3-inch guns into position on the hill to the right of the wood for support and directed Colonel Van Manning, commanding Walker’s brigade, to form a line of battle. Greene had brought up Captain John A. Tompkins’ battery of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, which had gone into position to the right of the burning Mumma farm buildings, where it was immediately fired on by Read’s battery.

One section of Tompkins’ Parrott rifles opened on Read’s guns, which were masked by a ridge; the other section knocked out one of Colonel S.D. Lee’s guns and blew up one of Lee’s caissons.

Battle smoke inundated the field, obscuring objects as close as 20 yards away. Greene’s men had a difficult time making out Dunker church, which lay 50 yards on their right, though it was obvious that a large body of Confederates had secreted themselves among the trees that surrounded the little church.

Three of Manning’s five regiments debouched from the West Woods on a poorly aligned and truncated front. The 48th North Carolina swirled around Dunker church while the 30th Virginia halted on the Hagerstown Pike to await the other regiments. The 46th North Carolina, on the left, obliqued to the right as the regiment debouched from the woods, then charged toward the Smoketown Road.

The soldiers had little chance of success. Less than 200 yards east of the Confederate position, Tyndale’s Ohioans waited for the command to fire. When the gray line approached to within 100 yards, the Federals opened fire at killing range. The musketry was brutally accurate, knocking down North Carolinians and Virginians by the score. Manning was unhorsed by the enemy fire and carried to the rear.

The Southern assault floundered on the Hagerstown Pike, stumbled at the wormwood fence line that bordered the Mumma farm and then receded. The Confederate troops began to flee for the shelter of the West Woods, then noticed, to their horror, that a line of blue-clad infantry, their colors waving in the morning breeze, was marching down the gentle slope of the Mumma swale.

As the tumult of battle roared about them, the Confederate regiments fled before the Federal onslaught. Tyndale’s men kept on coming, their faces and hands blackened with the residue of burnt powder. While the 102nd New York held the line, the remainder of the brigade joined Tyndale’s advancing line. On their right two more regiments, the 13th New Jersey and Purnell’s Legion, came up from the cornfield and East Woods in support.

The Federals probed deep into the West Woods, retaking the land abandoned an hour earlier by the defeated 2nd Division. Their advance went to ground 100 yards into the woods when they started taking artillery and small-arms fire from their left. Manning’s two remaining regiments, the 3rd Arkansas and 27th North Carolina, both under the command of Colonel John R. Cooke, had been detached to support a brace of 12-pounder Napoleons that had dropped trail about a quarter mile south of Dunker church.

The Union artillery soon emptied their ammunition chests and were expeditiously withdrawn. For half an hour, musketry filled the air as Cooke’s Confederates tried to push back Greene’s troops. Elements of Tyndale’s brigade pushed farther south, and Cooke responded by ordering the left three companies of the 27th North Carolina to center their fire on the exposed point.

The close-in fighting caused severe casualties on both sides. The bodies of Federal troops were found the next day stacked two and three high, and the 27th North Carolina suffered 63 percent casualties. The Federal troops withdrew from the exposed position in advance of their salient at Dunker church, and Cooke ordered the men of his command to withdraw into a cornfield and lie prone ‘to draw them on.’ The remainder of the Confederate regiment formed along a fence facing the enemy and in line with the vacillating battle front. Cooke’s tenuous position, which was the center of the entire Southern battle line, was held by two regiments that were speedily firing off their ammunition.

Meanwhile, Greene had entered the West Woods assuming that elements of Sedgwick’s 2nd Division were still ensconced in the northern portion of the woodlands, somewhere on his right. He ordered his two regiments holding the right, Purnell’s Legion and the 13th New Jersey, to refrain from firing northward for fear of hitting friendly troops. Unknown to Greene, just beyond his front and shielded by smoke, the 49th North Carolina, under the command of Lt. Col. Lee M. McAfee, lay coiled and ready to strike. Elements of the 48th North Carolina and the 2nd South Carolina also came up and took cover as Union artillerists fired salvos into the woods beyond Greene’s position.

Greene’s own artillery support had been severely handled by Confederate sharpshooters and was withdrawn just as the battery chests were being emptied. The replacements, Captain John Bruen’s 10th Battery, New York Light Artillery, and Captain Joseph Knap’s Battery E, Pennsylvania Light Artillery, were forced to clear away dead and wounded animals and men before they were able to unlimber their guns.

For about an hour both sides held their ground. The Confederates used the time to reinforce their position. Meanwhile, Greene sent couriers back to the East Woods, desperately calling for help. He knew that he had obtained a lodgement in the center of the Confederate battle line. If the salient could be hastily exploited, the Army of Northern Virginia could be split in half and defeated in detail.

No matter what happened, Greene would hold on as long as he could. Colonel Tyndale, in the meantime, had ridden out to Knap’s battery, collared a section of rifled pieces under the command of Lieutenant James D. McGill and ordered the protesting lieutenant to haul his guns into the West Woods and provide close support for his infantry. Tyndale’s actions, however, came a little late.

In the nether world of the West Woods, choked with the bodies of the dead and wounded and shrouded in the misty blue-gray smoke of musketry and artillery fire, the North Carolinians struck with a vengeance. On the right of Greene’s line, the 13th New Jersey, whose soldiers had observed the Rebels moving to their right and believed that they were surrendering, collapsed and broke under a galling and accurate fusillade of musketry. The New Jersey troops sprinted for the sanctuary of the Smoketown Road and the Federal artillery line. Their flight uncovered the little Maryland command, Purnell’s Legion, commanded by, Lt. Col. B.L. Simpson, who stoically held on until the overwhelming numbers of gray-clad attackers forced him to retire as well.

On Greene’s left, the majority of the 28th Maryland, 111th and 28th Pennsylvania also broke for the rear. The color guards of the three regiments and a few other soldiers stayed alongside the 66th, 5th and 7th Ohio at the bottom of the ridge below the church, but a feeling of dread hung over the Federals. The veterans knew that their time in the West Woods was short.

Cooke’s North Carolinians caught McGill’s rifled pieces coming into battery and dropped a number of horses and artillerists before they could unlimber. Tyndale, who had three horses shot from under him, was caught in the fire and received his second wound of the day–he was left for dead on the field. The colonel recovered from his wounds, however, and fought on until 1864, when he resigned his commission due to poor health and returned to his native Philadelphia.

The fire that had disconcerted McGill’s artillerists had come from Cooke’s left four companies, which he had maneuvered up to the fence and directed to fire upon the Union artillery. Cooke’s battle blood was raging now. He had been given discretionary orders from Colonel Manning, and he could see that the remnant of Greene’s command showed evidence of wavering. Cooke ordered a charge, and the 27th North Carolina and 3rd Arkansas scampered over the cornfield fence below Dunker church and headed toward the Federals. The four North Carolina regiments on Greene’s right were pressing hard on his flank, catching the Federals with enfilading fire.

Cooke’s assault from the southwest put an end to any organized resistance. It was time for the Federals to get out. Captain Charles D. Owen’s Battery G of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery had unlimbered in the Mumma swale 20 minutes earlier, relieving Tompkins’ battery, and had gotten into a duel with a Confederate battery to the south. ‘I saw our infantry retreating in great disorder toward me,’ Owen later reported, ‘and then about 150 yards off, closely followed by the rebels.’ Low on ammunition–he had expended 75 rounds–Owen limbered up and promptly left the field.

Cooke’s 27th North Carolinians had overrun McGill’s rifled piece but were taking a pounding from Lieutenant Edward Thomas’ Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery, located northeast of the church. Thomas opened with spherical case shot on Cooke’s men as they debouched from the woods onto the Mumma field east of the Hagerstown Pike. As the Confederates closed on his guns, the lieutenant ordered up canister. The results were predictably bloody.

Cooke rode out to the regiment’s color-bearer, who was racing desperately to stay ahead of his counterpart in the 3rd Arkansas, and had him guide the troops to the right to avoid the guns. On the right of the 27th North Carolina, the 3rd Arkansas went into the fight with a jaunty fiddler playing a square dance number. Both regiments, new to battle, were experiencing unqualified success, but Cooke’s little brigade was fighting without support. On his left, the four North Carolina regiments, temporarily under the command of Colonel Matthew W. Ransom, were blasted with double-shotted rounds of canister from Knap’s section, posted just beyond the Hagerstown Pike. Ransom withdrew his regiments into the haven of the West Woods.

Meanwhile, the 27th’s charge carried through the Ohioans, many of whom threw down their guns and surrendered. The vicious assault continued into the Mumma swale, where a large number of Tyndale’s and Stainrook’s soldiers had taken refuge. From behind rows of hay, the Union troops raised their muskets with handkerchiefs tied to them, and the Federals were directed to march for the Confederate rear. Nearly 300 prisoners were taken, although the Official Record only acknowledged 25 prisoners from both Tyndale’s and Stainrook’s brigades.

Cooke’s assault veered right because of Union artillery on his left and Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb’s brigade, which had come up on his right. The 27th was low on ammunition as well, and the regiment’s prisoners, who had not been disarmed, attempted to re-form in their rear. The 27th was forced to run a gantlet of fire and formed up with Cobb’s troops just as they were coming under a severe Federal assault themselves.

The Federals were repulsed with the last of the 27th’s ammunition, and for the remainder of the afternoon, the North Carolinians held their portion of the line without benefit of powder or ball. Captain James A. Graham reported that on four or five occasions Maj. Gen. James Longstreet sent couriers to Cooke ordering him to hold his position at ‘all hazards.’

Cooke’s reply was always the same: ‘Tell General Longstreet to send me some ammunition. I have not a cartridge in my command, but will hold my position at the point of a bayonet.’

Northwest of Dunker church, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. ‘Stonewall’ Jackson and cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart came riding up to Colonel Ransom. Jackson wanted Knap’s guns silenced, and Ransom replied that he had tried and failed and that beyond the guns a line of fresh Federal infantry was making its way onto the field.

Jackson ordered a young soldier up a nearby tree and told him to count battle flags. When the trooper got to 39, Jackson called him down. The remaining Confederate soldiers in the West Woods might be able to repulse a renewed Union assault, but Jackson knew they would be unable to launch a new one themselves.

Greene’s salient in the West Woods collapsed because of McClellan’s panicky mismanagement of the army. For nearly two hours, Greene’s two brigades had held a salient deep within the Confederate lines. They had valiantly provided McClellan with his best opportunity to defeat the Army of Northern Virginia and possibly end the rebellion in the eastern theater. Unfortunately, the soldiers’ sacrifice had been for naught.