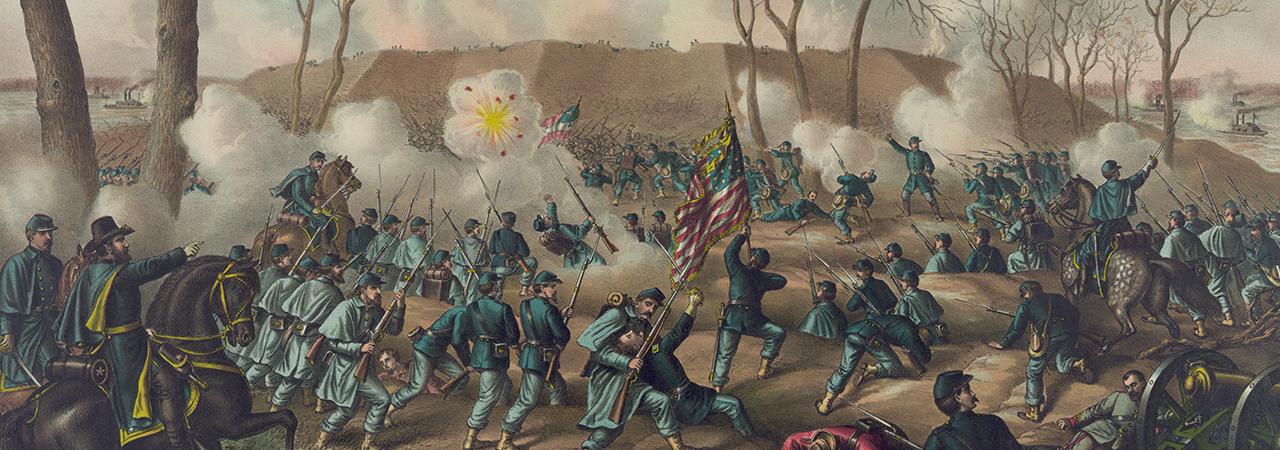

Fort Donelson

Stewart County, TN | Feb 13 - 16, 1862

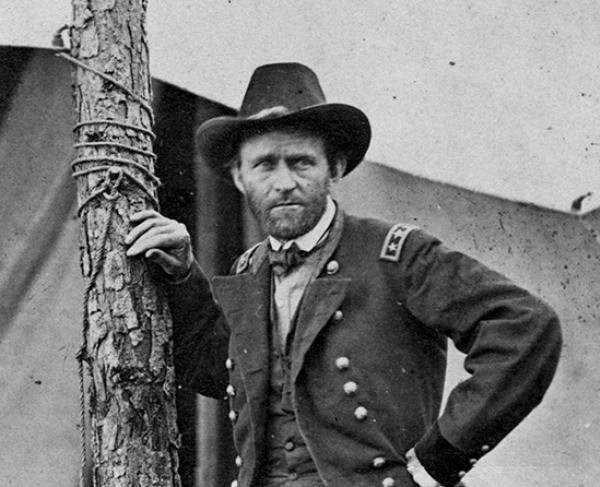

The decisive Union victory at Fort Donelson thrust Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant into the national spotlight and enabled Union advances up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

How it ended

Union victory. The capture of forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee were major victories for Ulysses S. Grant. Grant received a promotion to major general for his success and attained stature in the Western Theater, earning the nom de guerre “Unconditional Surrender Grant.”

In context

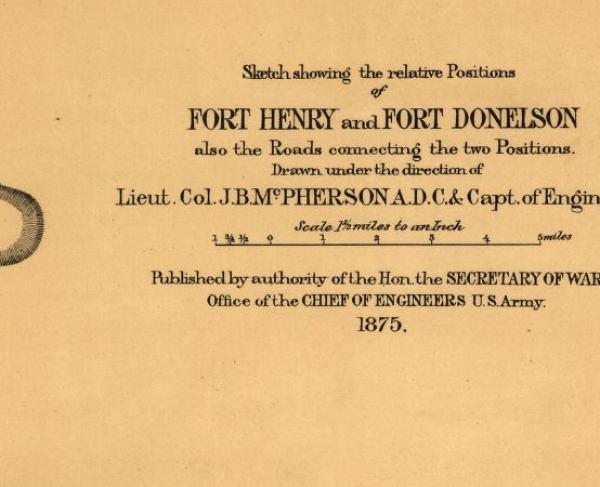

Early in the war, Union commanders realized that control of the major rivers would be the key to success in the Western Theater. After capturing Fort Henry on the Tennessee River on February 6, 1862, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant advanced 12 miles to invest Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Operations against Donelson were part of an amphibious campaign launched in early 1862 to push the Confederates out of middle and western Tennessee, thereby opening a path into the Southern heartland.

The Union victory at Fort Donelson forced the Confederacy to give up southern Kentucky and much of Middle and West Tennessee. The Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, as well as railroads in the area, became vital Federal supply lines, and Nashville became a huge supply depot for the Union army in the west.

After the fall of Fort Henry on February 6, 1862, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant is determined to move quickly to capture the much larger Fort Donelson, located on the nearby Cumberland River. However, Grant’s boast that he would take Donelson by February 8 quickly runs into challenges. Poor winter weather, late-arriving reinforcements, and difficulties in moving the ironclad ships up the Cumberland delay Grant’s advance on the fort.

Despite his conviction that no earthen fort could withstand the power of the Union gunboats, Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston allows the garrison at Fort Donelson to remain and even sends new commanders and reinforcements there. On February 11, Johnston appoints Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd as the commander of Fort Donelson and the surrounding region. Nearly 17,000 Confederate soldiers, combined with improved artillery positions and earthworks, convince Floyd that a hasty retreat is unnecessary. By February 13, most of Grant’s soldiers are positioned on the landward (western) side of the fort.

February 14. Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote’s ironclads move upriver to bombard Fort Donelson. The subsequent duel between Foote’s “Pook Turtles” and the heavier guns at the fort lead to a Union defeat. Many of Foote’s ironclads are heavily damaged, and Foote himself is wounded in the attack. Grant’s soldiers hear the Confederate cheers as the gunboats withdraw. While Grant contemplates an extended siege, the Confederate leadership devises a bold plan to mass their troops against the Union right to force open a path of escape.

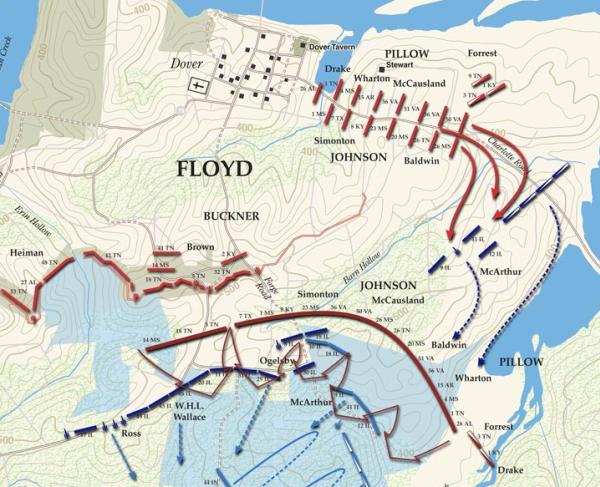

February 15. Early in the morning, the Confederate assault strikes the Union right and drives it back from its positions on Dudley’s Hill. Brigadier General John McClernand’s division attempts to reform its lines, but the ongoing Rebel attacks continue to drive his forces to the southeast. The Union army retreats, but inexplicably, Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow orders the attacking Rebel force back to their earthworks, causing them to abandon the hard-fought gains of the morning.

Seizing an opportunity, Grant orders McClernand and Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace to retake their lost ground and then rides to the Union left to order an attack upon the Confederate works opposite Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith’s division. Grant reasons, correctly, that the Confederate right must be greatly reduced in strength given the heavy assault from the Confederate left. Smith’s division surges forward and overwhelms the lone Confederate regiment occupying the rifle pits in advance of the Confederate line. Smith’s division captures large stretches of the earthworks before dark.

February 15 and 16. During the night, Confederate leaders discuss their options. Despite many disagreements, they determine that surrender is the only viable option for the garrison. Generals Floyd and Pillow abandon their men and flee across the river, while Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, disgusted with the Confederate decision to surrender, takes his cavalrymen and escapes down the Charlotte Road. Even with these defections, more than 13,000 Confederate soldiers remain in the fort.

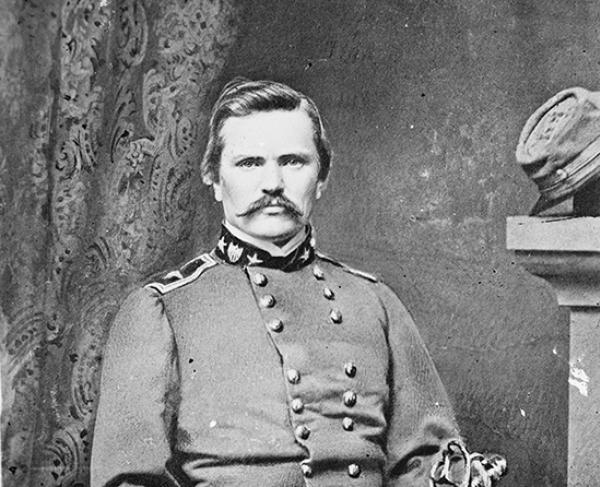

Poised to strike again, the Federal soldiers are surprised to see white flags flying above the Confederate earthworks. Brigadier General Simon B. Buckner, now in command, meets with Grant to determine the terms of surrender.

2,691

13,846

Buckner, who knew Grant at West Point, is hoping for generous terms from the Union general. He is disappointed to receive Grant’s terse response: “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” The Confederate general accepts Grant’s ultimatum but sends back a petulant reply: “The distribution of the forces under my command, incident to an unexpected change of commanders, and the over-whelming force under your command, compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms yesterday, to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose.”

But the exchange between the commanders grows more cordial when they meet face to face. In his memoirs, Grant looked back on that meeting with Buckner: “In the course of our conversation, which was very friendly, he said to me that if he had been in command, I would not have got up Donelson so easily as I did. I told him that if he had been in command I should not have tried in the way I did: I had invested their lines with a smaller force than they had to defend them, and at the same time had sent a brigade full 5,000 strong, around by water; I had relied upon their commander to allow me to come up safely outside their works.”

Grant is eventually promoted to major general for his victories in Tennessee. His subsequent success at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga earn him the rank of lieutenant general and appointment as commander of all Union armies. The favorable outcome for the Union in the Civil War ultimately results in his election as president of the United States in 1868.

The generals who fought at Fort Donelson might have been enemies, but they were hardly strangers. They first met at the United States Military Academy at West Point in the 1840s. After graduation, they both served in the Mexican-American War in General Winifred Scott’s division. In 1854, their paths crossed again in New York City. Grant had resigned from the army and fallen on hard times. Buckner fronted him some money to pay for his lodgings.

At Fort Donelson, Grant icily rejected Buckner’s surrender with conditions, but later offered him money should he need it during his capture. Grant agreed to treat wounded Confederates, provide hungry Rebel troops with rations, and forbade any formal ceremony designed to humiliate the men in their defeat: “There will be nothing of the kind. The surrender is now a fact. We have the fort, the men, the guns. Why should we go through vain forms and mortify and injure the spirit of brave men, who, after all, are our own countrymen?” These courtesies were not lost on Buckner, who remembered them long after the war.

In July 1885, with the Civil War twenty years behind them, Buckner decided to pay a visit to his old friend and opponent. Grant was, by then, terminally ill, but welcomed Buckner, explaining in a note, “I have witnessed since my sickness just what I wished to see ever since the war; harmony and good feeling between the sections….We may now look forward to perpetual peace at home and a national strength that will secure us from any foreign complication.”

Buckner is said to have once joked, “Grant…has… many merits and virtues…but he has one deadly defect. He is an incurable borrower and…knows of only one limit—he wants what you’ve got. When I was poor, he borrowed $50 of me; when I was rich, he borrowed 15,000 men.” Somehow, their relationship survived Fort Donelson. In keeping with Grant’s hopes for reconciliation and unity, two former Union generals and two former Confederate generals served as pallbearers at his funeral. One of them was Simon Buckner.

News of the capture of Fort Donelson, combined with the victory at Fort Henry only 10 days before, sped through the North and brought delight to those supporting the Union cause. Grant was suddenly a national hero—to all, it seemed, except his superior officer, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck. While Halleck was instrumental is supporting Grant’s campaign, he had not been stationed in Tennessee and had not participated in the engagements there. Grant received the public’s adoration. Halleck was simply ignored.

Jealous of the attention given to a man he felt was beneath him, Halleck soon started a behind-the-scenes effort to undermine Grant. He sent a series of letters to the army General-in-Chief, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. First, Halleck suggested to McClellan that the army promote C. F. Smith over Grant, pointing out that “by his coolness and bravery at Fort Donelson when the battle was against us, [Smith] turned the tide and carried the enemy’s outworks.” Next, he sought a promotion for himself, imploring McClellan: “I must have command of the armies in the West. Hesitation and delay are losing us the golden opportunity.... May I assume the command? Answer quickly.”

Finally, he made false assertions about Grant: “I have had no communication with General Grant for more than a week. He left his command without my authority and went to Nashville.…I can get no returns, no reports, no information of any kind from him.”

McClellan took the bait, replying: “Generals must observe discipline as well as private soldiers. Do not hesitate to arrest him at once if the good of the service requires it, and place C.F. Smith in command.” Halleck was all too happy to do so. Grant was stunned, writing later, “Thus in less than two weeks after the victory at Donelson, …I was virtually in arrest and without a command.”

Halleck’s false allegations eventually caught up with him. When President Lincoln demanded proof of his star general’s misdeeds, Halleck could not deliver any concrete evidence against Grant. Halleck slipped out of the lie he created by saying that Grant’s questionable actions were well intentioned and for the public good, and then he cleared him: “There never has been any want of military subordination on the part of General Grant….”

Grant and Halleck worked together through the rest of the war. Grant never knew of Halleck’s direct role in the episode that almost cost him his career until twenty years later, when he was doing research for his Personal Memoirs.

Fort Donelson: Featured Resources

All battles of the Federal Penetration up the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers Campaign

Related Battles

24,531

16,171

2,691

13,846