The Wilderness

Spotsylvania and Orange Counties, VA | May 5 - 7, 1864

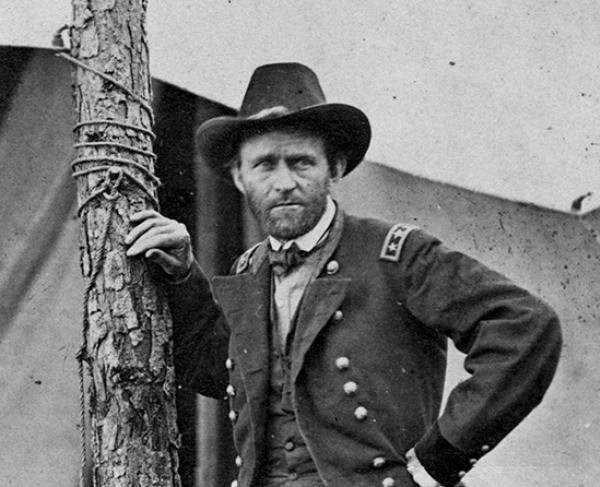

The bloody Battle of the Wilderness, in which no side could claim victory, marked the first stage of a major Union offensive toward the Confederate capital of Richmond, ordered by the newly named Union general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant in the spring of 1864.

How it Ended

Inconclusive. After two days of combat, the two armies were essentially where they had been at the start of the battle. The Union army suffered more than 17,500 casualties over 48 hours, thousands more than the toll endured by the Confederates. Despite the costly nature of the battle, Grant refused to order a retreat, having promised President Abraham Lincoln that regardless of the outcome, he would not halt his army’s advance.

In Context

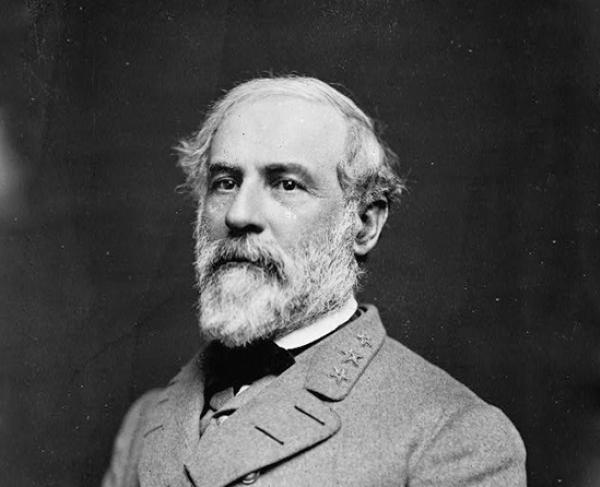

In March 1864, Lincoln named Grant general-in-chief of all Union armies. Grant immediately began planning a major offensive toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. The primary goal of this Overland Campaign was to engage Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in a series of battles to defend the Southern capital, making it impossible for Lee to send troops into Georgia, where Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman was advancing on Atlanta.

Grant decided to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. He would concentrate on general strategy while Meade would oversee tactical matters. By early 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia faced each other across the Rapidan River in central Virginia. The two armies eventually met in the dense woods known as the Wilderness. The fight would prove deadly for both sides, and after 48 hours of intense combat, neither was the victor. Despite the outcome, Grant did not retreat. To the relief of President Lincoln and the joy of his men, the general continued his advance toward Richmond.

In anticipation of Grant's expected onslaught, Lee leaves Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's Second Corps and Lt. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill's Third Corps behind earthworks along the Rapidan River. Meanwhile, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's First Corps wait in the rear at Gordonsville, ready to reinforce the Rapidan works or shift to Richmond, as necessary. Lee's cavalry, under Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart, patrols the countryside past the ends of the Rapidan line. It is Lee's hope that his scouts and cavalry will alert him in time to respond once Grant reveals his intentions.

In early May, the Army of the Potomac and independent Ninth Corps leave their winter camps in Culpeper County and march south toward the Rapidan River fords. At dawn on May 4, Union cavalry splash across Germanna Ford, dispersing Confederate cavalry pickets and enabling Union engineers to construct two pontoon bridges. General Gouverneur K. Warren’s Fifth Corps thumps across the ford and enters the dense, forbidding woodland known as the Wilderness. Grant intends to push the army through the rough terrain into open ground as quickly as possible, yet he will not shy away from attacking Robert E. Lee’s army if he gets the opportunity.

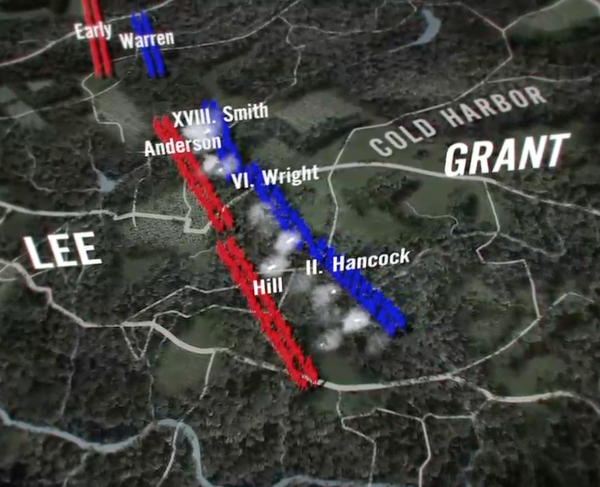

May 5. As Gen. Warren advances, he receives word that Confederate infantry is approaching from the west on the Orange Turnpike. His commander, Maj. Gen. George Meade, orders Warren to strike the Confederates. The Fifth Corps chief, however, is apprehensive about making an attack in the Wilderness, where impenetrable thickets will make it difficult to maintain a battle line and will nullify the Federals’ numerical superiority. Warren’s protests notwithstanding, his corps move to a position astride the turnpike.

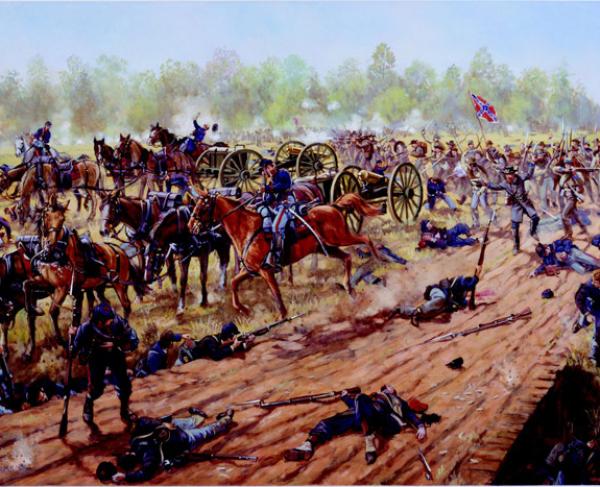

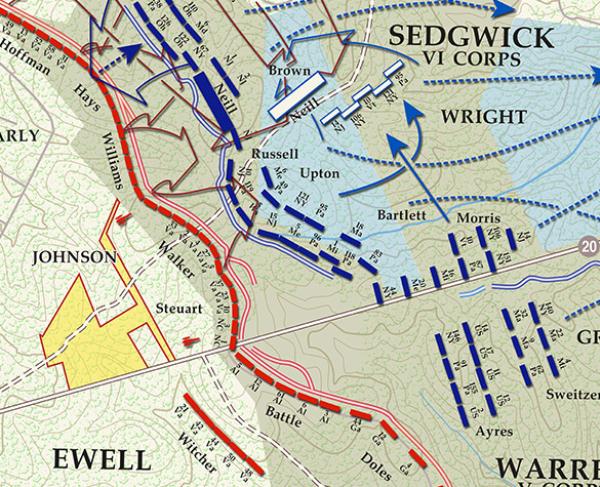

While Warren and Meade debate the merits of an attack along the Orange Turnpike, Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Confederate corps halt three miles west of Wilderness Tavern and build strong earthworks on the west edge of Saunders Field. When Warren’s men step out of the woods and into the open, Ewell’s troops exact a fearful toll in casualties. The Yankees achieve a momentary breakthrough, but swift action by Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon’s brigade seals the breach. The arrival of the Union Sixth Corps does little more than broaden the front and lengthen the list of casualties.

Shortly after Warren runs into the Confederates on the turnpike, Union Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford, at the William Chewning farm, observes another enemy column headed east on the Orange Plank Road toward its intersection with the Brock Road. This is a serious threat: if the Confederates gain possession of that area, they can drive a wedge between Warren’s corps on the turnpike, and Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps, which passed Warren and moved further south. Meade quickly dispatches Brig. Gen. George W. Getty’s Sixth Corps division to seize the crossroads. Around 4:00 p.m., Getty attacks, his men tearing through the tangled thickets in a vicious close-range fight with Gen. A.P. Hill’s corps. Hancock soon arrives and rushes forward to support Getty, continuing the fight until nightfall.

May 6. Hancock’s Federals resume the offensive that morning. A.P. Hill’s tired troops are forced back, and the Confederates seem on the verge of collapse. Brig. Gen. John Gregg’s Texas Brigade from Gen. James Longstreet’s corps arrive in time to stave off disaster. A pair of flank attacks—by Longstreet south of the Plank Road and by Gordon north of the turnpike –help break the stalemate and force the Federals behind breastworks. However, just as Longstreet’s men are on the brink of success, Longstreet is felled by an errant volley from his own troops.

With Longstreet wounded, Lee coordinates the final attacks on the Union line along the Brock Road. Hampered by the heavy brush, the Confederates stumble forward without cohesion until they reach obstructions in front of the Union line. There, they are stopped cold by the crashing volleys from Hancock’s veterans. In one spot, Confederate troops dash forward and plant their flags on the burning works, but their success is short-lived. Within minutes, Union troops counterattack and reclaim the works.

May 7. Both sides dig in and await attack. Realizing that he can make no further headway in the Wilderness, Grant orders Meade’s army to pull out after dark.

17,000

13,000

Grant’s army suffers nearly 18,000 casualties in the Wilderness, almost twice as many as Lee’s, but his troops are not dispirited. After sustaining heavy losses in their battles with Lee, former Union commanders Hooker and Burnside had retreated. So, when the Union troops discover that their new leader—Grant—is continuing to advance, the Federals rejoice. On May 7, Grant directs Union engineers to take up the pontoon bridges at Germanna Ford and orders his corps commanders to march toward Spotsylvania Court House.

On May 7, exhausted Federal troops left their trenches and began marching south, toward the lower edge of the Wilderness. As Grant came riding to the head of the troops, his soldiers slowly realized they were not in retreat (as had been assumed) and broke into wild cheering. Grant’s aide-du-camp, Col. Horace Porter, described the spontaneous celebration.

In the past, when the Army of the Potomac had failed to win a victory south of the Rappahannock it had retreated back across the river to regroup. But Grant shrugged off the casualties in the Wilderness and kept up momentum and morale by continuing to move south. It was the beginning of an arduous month and a half of almost continuous fighting that ended with Lee’s weary troops desperately dug into a final defensive line around Richmond.

For Gen. Lee, massively outnumbered and outgunned by Union forces, the harsh terrain of the Wilderness was preferable, as a fight in the dense woods would prevent Grant from using his artillery effectively and provide cover for the smaller Confederate force. But smoke from gunpowder blinded the soldiers and fires lit by exploding shells spread through the dry woods, making the Wilderness an inferno for all the troops ensnared there. The unfavorable terrain reduced the two-day battle to a series of bloody skirmishes in which almost 30,000 men on both sides were killed or wounded. Warren L. Goss, a soldier in Hancock’s Second Corps, described the horror of the first day’s fight in the Wilderness:

Goss’s account confirms why the Wilderness was often described as the battle “which no man saw or could see.”

The Wilderness: Featured Resources

All battles of the Grant's Overland Campaign

Related Battles

101,895

61,025

17,000

13,000