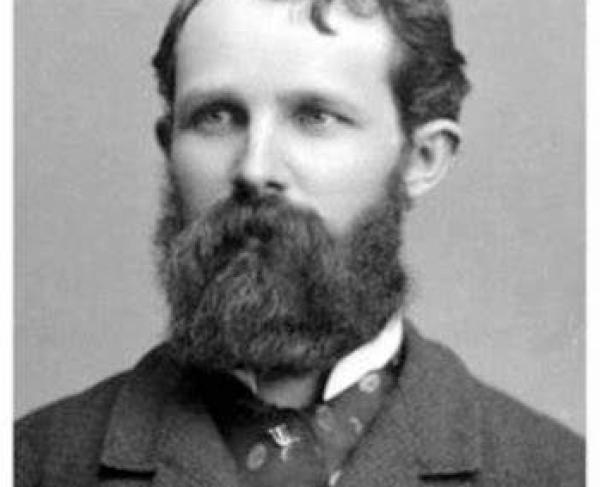

Robert Gould Shaw

"There they march, warm-blooded champions of a better day for man. There on horseback among them, in his very habit as he lived, sits the blue-eyed child of fortune, upon whose happy youth every divinity had smiled . . . "

Oration by William James at the exercises in the Boston Music Hall, May 31, 1897, upon the unveiling of the Shaw Monument.

Despite his image in the 1989 film Glory, Robert Gould Shaw was a reluctant leader of the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry, one of the first African American regiments in the Civil War. At the time he took command of the 54th in 1863, Shaw was 25 years old and had already taken part in several battles with his old regiment, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, including engagements at Cedar Mountain and Antietam. Shaw was hesitant to leave his comrades for service in a regiment that he doubted would ever see action.

Born to a prominent Boston abolitionist family in 1837, Shaw did not share the passion of his parents for freeing the slaves. As a young man, he spent several years studying and traveling in Europe before attending Harvard University from 1856 to 1859. Unsure of what he wanted to do with his life, Shaw dropped out before completing his studies.

When war came in 1861, Shaw seemed to find a purpose, and he immediately enlisted in the 7th New York Infantry, and served in the defense of Washington, DC for 30 days, after which the regiment was dissolved. In May of that year, Shaw joined the 2nd Massachusetts as a second lieutenant, serving for two years and attaining the rank of Captain.

Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew, a strong abolitionist, recruited Shaw in March of 1863 to raise and command one of the first regiments of African American troops in the Union army, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Initially taking the command to appease his mother, Shaw eventually grew to respect his men and believed that they could fight as well as white soldiers. He was eager to get his men into action to prove this. When he learned that black soldiers were to receive less pay than whites, Shaw led a boycott of all wages until the situation was changed.

On May 28, 1863, Shaw led the 54th in a triumphant parade through Boston to the docks, where the regiment departed for service in South Carolina. Shaw had married Annie Kneeland Haggerty just 26 days before.

Initially assigned to manual labor details, the 54th did not see real action until a skirmish with Confederate troops at James Island on July 16. Two days later, Shaw and his men were among the units chosen to lead the assault on Battery Wagner, part of the defenses of Charleston. Shaw was killed in the charge, bravely urging his men forward, but the 54th had proven that they were as brave as anyone, black or white.

Confederate General Johnson Hagood refused to return Shaw’s body to the Union army, and to show contempt for the officer who led black troops, Hagood had Shaw’s body buried in a common trench with his men. Rather than considering this a dishonor, Shaw’s father proclaimed,

“We would not have his body removed from where it lies surrounded by his brave and devoted soldiers....We can imagine no holier place than that in which he lies, among his brave and devoted followers, nor wish for him better company – what a body-guard he has!”