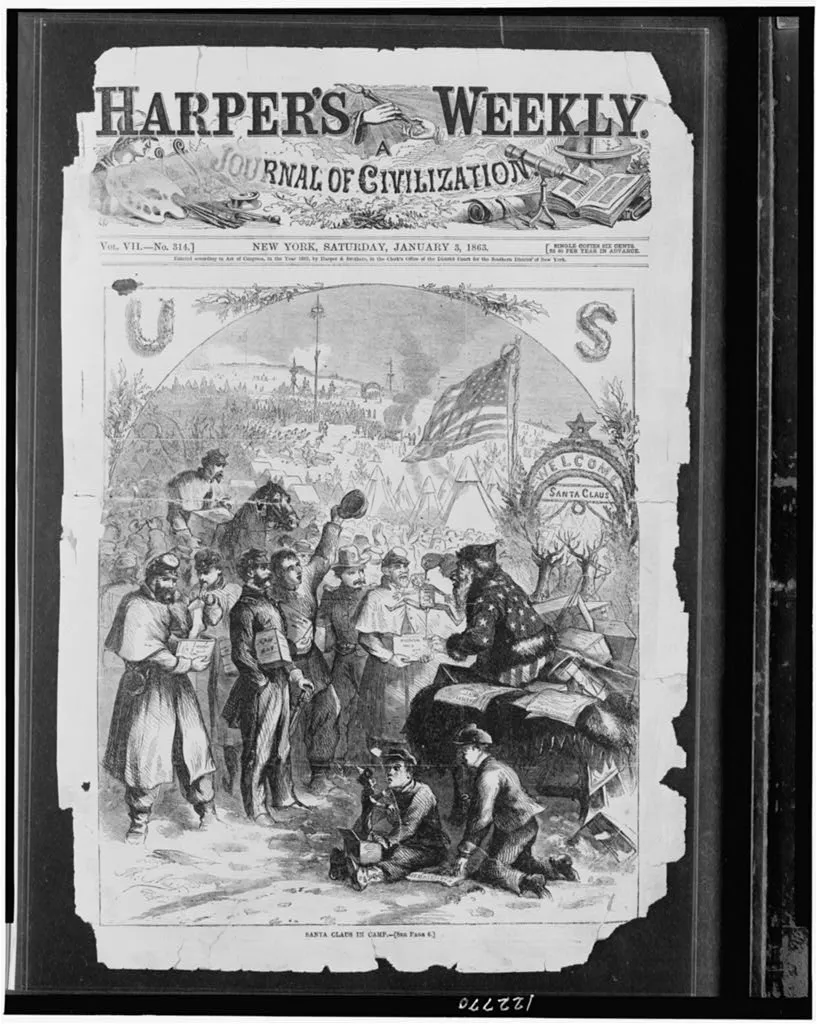

It can be difficult to relate to the men and women of the Civil War era. Despite the extraordinarily different circumstances in which they found themselves, however, we can connect with our forebears in traditions such as the celebration of Christmas. By the mid-19th century, most of today's familiar Christmas trappings — Christmas carols, gift giving and tree decoration — were already in place. Charles Dickens had published “A Christmas Carol” in 1843 and indeed, the Civil War saw the first introductions to the modern image of a jolly and portly Santa Claus through the drawings of Thomas Nast, a German-speaking immigrant.

Civil War soldiers in camp and their families at home drew comfort from the same sorts of traditions that characterize Christmas today. Alfred Bellard of the 5th New Jersey noted, “In order to make it look much like Christmas as possible, a small tree was stuck up in front of our tent, decked off with hard tack and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc.” John Haley, of the 17th Maine, wrote in his diary on Christmas Eve that, “It is rumored that there are sundry boxes and mysterious parcels over at Stoneman’s Station directed to us. We retire to sleep with feelings akin to those of children expecting Santa Claus.”

In one amusing anecdote, a Confederate prisoner relates how the realities of war intruded on his Christmas celebrations: “A friend had sent me in a package a bottle of old brandy. On Christmas morning I quietly called several comrades up to my bunk to taste the precious fluid of…DISAPPOINTMENT! The bottle had been opened outside, the brandy taken and replaced with water…and sent in. I hope the Yankee who played that practical joke lived to repent it and was shot before the war ended.”

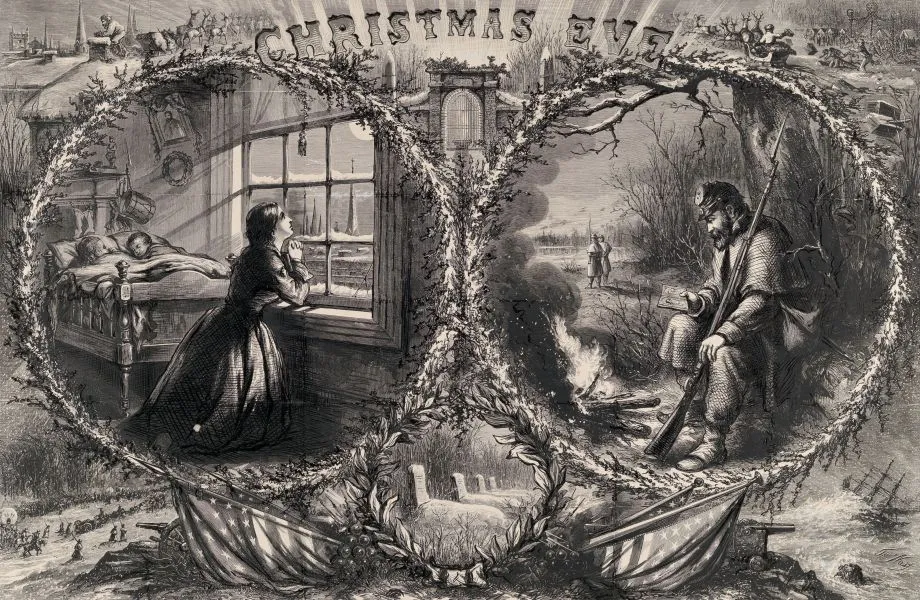

For many, the holiday was a reminder of the profound melancholy that had settled over the entire nation. Southern parents warned their children that Santa might not make it through the blockade, and soldiers in bleak winter quarters were reminded, more acutely than ever, of the domestic bliss they had left behind. Robert Gould Shaw, who would later earn glory as the commander of the 54th Massachusetts, recorded in his diary, “It is Christmas morning and I hope a happy and merry one for you all, though it looks so stormy for our poor country, one can hardly be in merry humor.” On the Confederate home front, Sallie Brock Putnam of Richmond echoed Shaw’s sentiment: “Never before had so sad a Christmas dawned upon us…We had neither the heart nor inclination to make the week merry with joyousness when such a sad calamity hovered over us.” For the people of Fredericksburg, Virginia, which had been battered only a matter of days before Christmas, or Savannah, Georgia, which General Sherman had presented to President Lincoln as a gift, the holiday season brought the war to their very doorsteps.

Christmas during the Civil War served both as an escape from and a reminder of the awful conflict rending the country in two. Soldiers looked forward to a day of rest and relative relaxation, but had their moods tempered by the thought of separation from their loved ones. At home, families did their best to celebrate the holiday, but wondered when the vacant chair would again be filled.