Though overshadowed by the devastatingly bloody battles waged between large-scale armies, guerilla warfare tactics were employed by both the Union and the Confederacy throughout the Civil War — particularly in contested areas and Border States. With its deeply divided loyalties and dueling military presences, Missouri was a hotbed of guerrilla activity early in the war, a situation that only intensified after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.

In Missouri and other Border States of the Western Theater, guerilla fighters — regardless of which side they favored — were commonly called “bushwhackers,” although pro-Union partisans were also known as “jayhawkers,” a term that had originated during the pre-war Bleeding Kansas period.

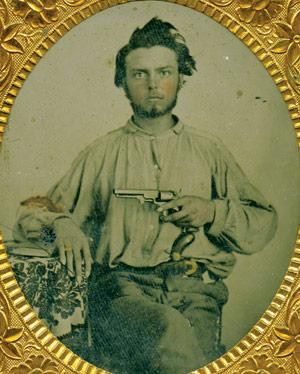

Often, guerilla fighters could only loosely be called soldiers, as these small partisan bands acted independently and outside the strategic framework of formal armies and command structures. Without official uniforms, they presented challenges for opposing forces when captured — should they be treated as enemy combatants or civilian criminals? Common tactics used by bushwhackers included ambushing individuals, families and smaller army detachments, or raiding farms to steal supplies, foodstuffs and anything else of value.

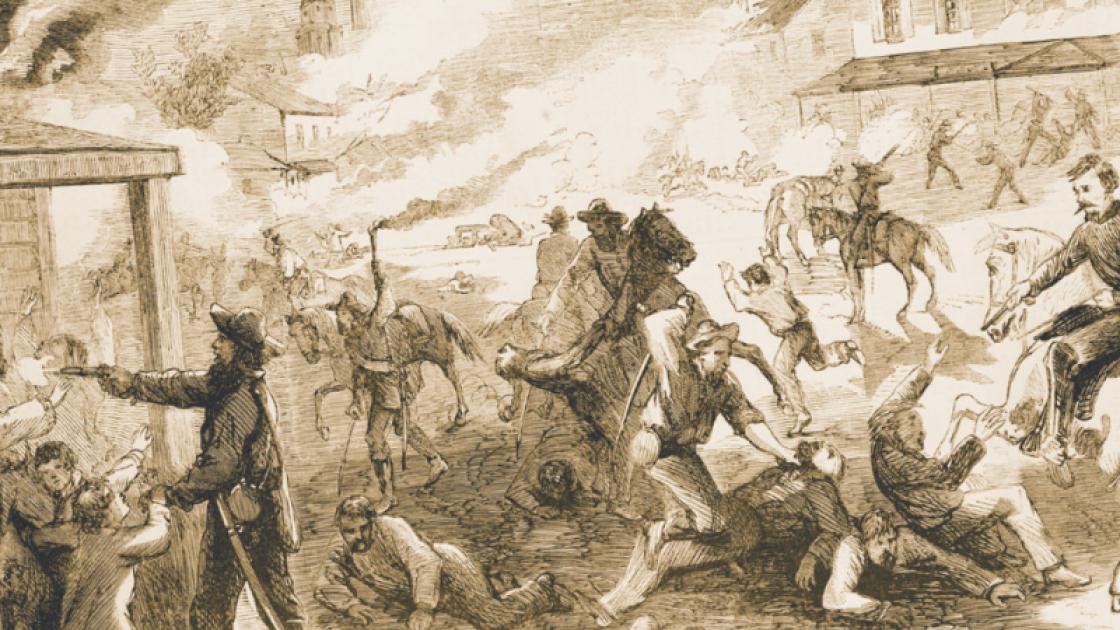

The enmity between partisan forces was tremendous. In September 1861, pro-Union forces led by U.S. senator James H. Lane raided the town of Osceola, Mo., executing nine men after a hastily arranged court martial. The violence continued, as several Missouri towns were plundered and burned, eventually culminating with Confederate partisan rangers recording that the war’s most famous bushwhacker operation — the Lawrence Massacre — was undertaken, in part “in retaliation for Osceola.”

Although not the only Confederate partisan group in the region, William Clarke Quantrill’s Raiders soon emerged as the most infamous. In August 1862, they were officially mustered into the Confederate Army under the Partisan Ranger Act passed in April of that year. Nonetheless, their ambushes against Union supply convoys, military patrols and detachments and attacks on pro-Union civilians were frequently undertaken without the knowledge or input of the Confederate government.

Responding to this threat, Union Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing, commanding the District of the Border, issued a general order that any civilian aiding the raiders would be arrested, including women and children. When a jail housing some of these prisoners collapsed in August 1863, killing five women — including the 14- year-old sister of one of Quantrill’s most trusted lieutenants — Quantrill and company organized several partisan groups for a combined raid on the Kansas town of Lawrence, killing nearly 200 men and boys.

The bloodletting continued throughout the war, with attack in retaliation for attack even after the Confederate Congress, under pressure from traditional military leaders, repealed the Partisan Ranger Act in February 1864. Not even the cessation of formal hostilities could quiet all of these guerrilla actions. Some partisan Confederates made for Mexico rather than be forced into a formal surrender, and veterans of Quantrill’s Raiders formed the nexus of the James-Younger Gang, infamous for a series of bank and train robberies in the decades following the war.

Related Battles

1,235

1,095