10 Facts: The Battle of Chickamauga

Learn more about the Battle of Chickamauga, the Confederacy's greatest victory in the West.

Fact #1: Chickamauga was the largest Confederate victory in the Western theater.

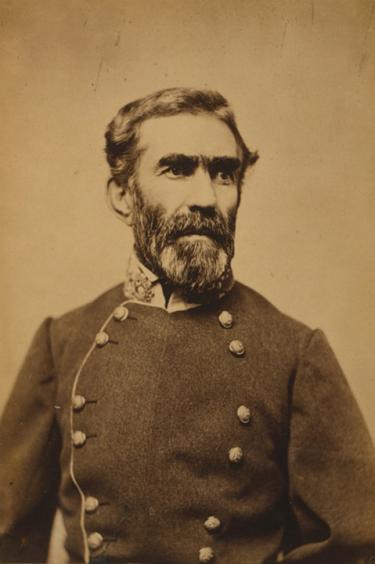

At the end of a summer that had seen the disastrous Confederate loss at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the triumph of the Army of Tennessee at Chickamauga was a well-timed turn around for the Confederates. Bragg’s forces at Chickamauga secured a decisive victory, breaking through Federal lines after two days of fierce fighting and the Yankee army into a siege at Chattanooga. Bragg, however, could not afford another victory like the one at Chickamauga; he lost nearly twenty percent of his effective fighting force. With 16,170 Union and 18,454 Confederate casualties, the Battle of Chickamauga was the second costliest battle of the Civil War, ranking only behind Gettysburg, and was by far the deadliest battle fought in the West.

Fact #2: The Confederate forces outnumbered the Federals at Chickamauga.

Hoping to bolster the Army of Tennessee, Mississippi divisions under Gen. Bushrod Johnson and troops from the Army of Northern Virginia under Gen. James Longstreet were sent to Georgia—the Confederates’ attempt to transfer troops from one theater to another to achieve numerical superiority. Longstreet had long advocated a concentration of troops in the West, and despite the resistance of Robert E. Lee, who believed the war would be decided in Virginia, in August Longstreet headed south with two divisions from the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. This move paid off. Bragg, once reinforced by Johnson and Longstreet, had 65,000 men at his command, compared to the 60,000 men of the Union Army of the Cumberland.

Fact #3: The Union army did not expect to encounter the Confederates at Chickamauga.

After pushing the Confederates out of Chattanooga early in September, Union Gen. William S. Rosecrans assumed that Bragg’s demoralized army would continue retreating further south into Rome, Georgia. He divided his army into three corps and scattered them throughout Tennessee and Georgia, with Gen. Thomas Crittenden remaining in Chattanooga, and Generals Alexander McCook and George H. Thomas positioned further to the South. When Thomas’s men encountered a large Confederate force at Davis’ Cross Roads, however, Rosecrans realized his mistake – Bragg had in fact concentrated his men at LaFayette, Georgia, where he was expecting reinforcements and was in close proximity to a vulnerable corps of Rosecrans’ army. Rosecrans immediately ordered his forces to concentrate near Thomas at Stevens’ Gap. When Bragg’s army crossed West Chickamauga Creek, the Federals had a fight on their hands.

Fact #4: A fierce skirmish between Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and Union troops at Reed's Bridge marked the opening of the battle.

Early on September 18, Gen. Bushrod Johnson approached Reed’s Bridge with five infantry brigades, supported by Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry. Union Col. Robert Minty, who was charged with guarding Reed’s Bridge, was positioned about a mile east with three infantry regiments supported only by a battalion of cavalry. At 7:30 a.m., Forrest began to skirmish with Minty, who could see long lines of Confederate infantry headed his way. Receiving well-armed reinforcements from Col. John T. Wilder’s Lightning Brigade, the Union troops resisted until noon, when, in one quick onrush, Minty was rapidly pushed across the bridge. He continued to delay Forrest’s cavalry until 3:30, when the Confederates began to ford the river just downstream.

Fact #5: State-of-the-art repeating rifles played a decisive role in the battle.

Repeating rifles demonstrated their fatal efficiency at the Battle of Chickamauga. Col. John T. Wilder’s famous “Lightning Brigade” of mounted infantry was the first brigade in the Federal army to be armed with Spencer rifles, which enabled the shooter to get off 14 rounds per minute, as opposed to the 2-3 shots per minute of an average Civil War rifle. Their superior guns enabled the Lightning Brigade to hold Alexander’s Bridge on September 18th in the face of two charges from Gen. St. John Liddell’s Confederates, delaying the Southerners from crossing the creek. The superiority of the repeating rifle would again be demonstrated by the Lightning Brigade on September 20th when, during Longstreet’s breakthrough of the Union line, a division under Gen. Thomas Hindman reached the Widow Glen’s House and were pushed back by unexpected fire from the Spencers of Wilder’s Brigade. The fire was so heavy that Longstreet momentarily thought a new Federal corps had arrived on the battlefield.

Another unit, the 21st Ohio also demonstrated the usefulness of repeating rifles at Horseshoe Ridge. These men were armed with Colt repeaters and were vital to holding the last Union stronghold on the field. The carnage caused by the rifles shocked even the Union men wielding them. After the battle, Wilder wrote “It actually seemed a pity to kill men so. They fell in heaps; and I had it in my heart to order the firing to cease, to end the awful sight.”

Fact #6: Thick woods and swampy terrain made Chickamauga Creek a particularly deadly place to fight.

Chickamauga Creek, which has been roughly translated from Cherokee to mean “River of Death,” was deep, tree-lined, and bordered by rocky banks. Most of the areas in which the armies fought were in thickets that presented, as one historian has called it, a “bristling, sticky, irritating obstacle.” Throughout September 18 and 19, the terrain made clearly drawn battle lines impossible: commanding officers on both sides had little-to-no view of the field, and the armies constantly shifted positions as they unexpectedly ran into each other. The fluid battle lines in dense woods led to vicious, close quarters combat. Throughout the 19th, as Gen. John Bell Hood moved against the Federal right and Gen. Patrick Cleburne led a sunset assault on the left, units could not easily see or cooperate with each other, leading to extraordinarily high casualties.

Fact #7: Command confusion and luck enabled the Confederate victory.

On the morning of September 20th, in the face of repeated Confederate assaults, Rosecrans was furiously working to shift men to his hard-pressed left. Once again, the terrain at Chickamauga proved disastrous when the heavy woods concealed a Federal division, causing one of Rosecrans’ staff officers to report that there was a gap in the Union line. Without verifying for himself, Rosecrans ordered Gen. Thomas Wood to shift his division, an order which Wood knew to be a mistake yet followed to avoid reprimand. In a stroke of luck for the Confederates, Gen. James Longstreet had amassed eight brigades ready to charge at the Union line. At 11:30 a.m., Longstreet ordered the charge forward, unwittingly aiming his striking force in the breach Wood had just created. The Confederates slammed through the line, routing the panicked Union soldiers who promptly scattered in retreat.

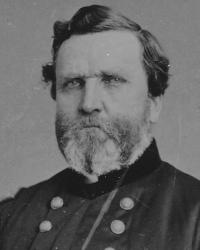

Fact #8: Gen. George H. Thomas earned the name “The Rock of Chickamauga” for his steadfast defense of Horseshoe Ridge.

After Longstreet’s breakthrough, Union resistance crumbled as unit after unit fell back in disorder. With Rosecrans himself retreating back to Chattanooga, Gen. George H. Thomas took control of what was left of the army. His own troops held their ground at Horseshoe Ridge, a strong defensive position. Thomas rallied retreating men from other commands, encouraging them to halt on Snodgrass Hill and begin building breastworks. Longstreet, meanwhile, asked Bragg to reinforce his battle-weary troops, yet Bragg refused. Throughout the afternoon, Longstreet’s assaults on Horseshoe Ridge were repeatedly repulsed. Thomas soon received orders from Rosecrans to take command of the army and order a general retreat, which he did soon after nightfall. For his determination to hold the Union position, even after his commanding officer had left the field, Thomas was later called “the Rock of Chickamauga,” and was considered by Ulysses S. Grant to be one of the finest generals in the Federal army.

Fact #9: Bragg’s failure to pursue Rosecrans turned the Southern victory into a strategic defeat.

After the Confederate victory on the 20th, Generals Longstreet and Forrest wanted to push on the next morning to destroy Rosecrans’ army before it had a chance to reorganize. Although Bragg’s original plan was the destruction of the Army of the Cumberland and the recapture of Chattanooga, the results of two days of bitter fighting now stalled him. In the Battle of Chickamauga, Bragg had lost 20,000 men – more than twenty percent of his force. Ten Confederate generals had been killed or wounded, and the losses among his junior officers had been severe. With an eye on his losses, Bragg refused to pursue the fleeing Federals, a move which turned the decisive Southern victory at Chickamauga into a strategic defeat. Instead, Bragg planned to occupy the heights surrounding Chattanooga and lay siege to the city. Just two month later, the reinforced Federals drove the Army of Tennessee from their positions around Chattanooga, permanently securing Northern control of the city. Chickamauga—a battle which cost a Bragg fifth of his army—was turned into a hollow victory.

Fact #10: The Chickamauga Battlefield was a part of the very first National Military Park

Toward the end of the 19th century, Civil War veterans including the Society of the Army of the Cumberland and the Chickamauga Memorial Association rallied support for creating a national park to preserve the battlefield at Chickamauga as well as nearby sites at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. Congressman Charles H. Grosvenor (who commanded the 18th Ohio at Chickamauga) introduced the bill in Congress in 1890; it was signed by President (and fellow Civil War veteran) Benjamin Harrison in August of that year. Dedicated on the Battle of Chickamauga's 32nd anniversary in 1895, the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park became the first such park established by the Federal government, followed by Shiloh, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Antietam.

Learn More: The Civil War In4: War in the West