10 Facts: Charleston in the Civil War

The city of Charleston, South Carolina, played an important role in the Civil War. It was the place where the conflict began, but the city also impacted the war's outcome and aftermath. Learn more about Charleston during the Civil War with these ten facts.

Fact #1: In 1860 South Carolina’s Black population outnumbered its white population.

Long a part of the Atlantic slave trade, Charleston boasted a growing African-American population in the early nineteenth century. By 1860, however, the city and the state’s Black residents outnumbered its white population. The 1860 census recorded 412,320 African Americans (including slaves) in South Carolina, with a population of some 291,300 whites. This resulted from Charleston's prominence as a hub in the domestic slave trade. Though legal importation of slaves ended in 1808, ports such as Charleston witnessed the arrival of millions of slaves from the Upper South to the Deep South in the antebellum years. Thus, fears of a slave rebellion prevailed throughout the state, particularly among the slaveholding elite of Charleston.

Fact #2: Charleston was known as the “Birthplace of Secession” for its role in South Carolina’s decision to secede from the Union.

On December 20, 1860, the South Carolina General Assembly convened in Charleston's Institute Hall following the presidential election of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s opposition to the expansion of slavery prompted the Assembly to unanimously vote for an ordinance of secession, announcing its withdrawal from the Union on December 20. After years of threatening secession, South Carolina finally broke its ties to the United States. Fire-eaters from Charleston traveled throughout the South to persuade other slaveholding states to secede. Charleston’s convention garnered the support of additional Southern states and eventually led to the creation of the Confederate States of America.

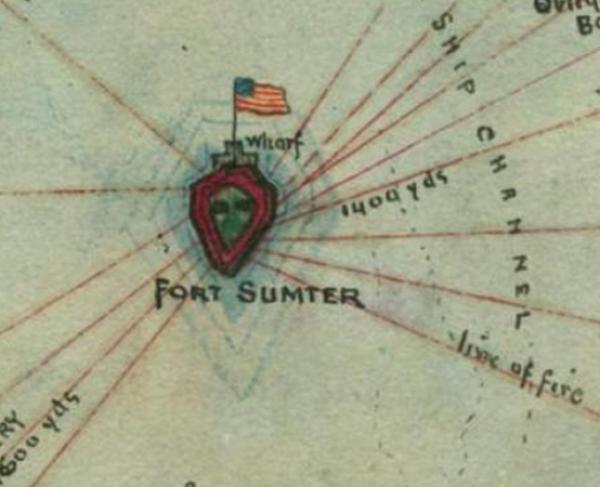

Fact #3: A merchant ship known as the Star of the West attempted to resupply Fort Sumter in January 1861.

Following South Carolina’s secession, General P.G.T. Beauregard took command of the new Confederate forces occupying the fortifications around the incomplete Fort Sumter. South Carolina militia quickly seized and revitalized old or abandoned forts around Charleston to surround the incomplete Fort Sumter located in the middle of the harbor. Early in 1861, President James Buchanan authorized the Star of the West to resupply the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. On January 9, the ship arrived in Charleston with relief supplies, but Citadel cadets fired as it entered the harbor. As another supply ship neared the fort on April 9, 1861, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the fort to be fired upon. After Fort Sumter surrendered, Star of the West helped evacuate its garrison.

Fact #4: P.G.T. Beauregard was a student of Major Robert Anderson at West Point before they faced one another at Fort Sumter in 1861.

The young Creole and Louisiana native Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1834. There he encountered Robert Anderson, then a lieutenant, as an artillery instructor. The extent of their relationship during this time is unclear, however, Anderson instructed several of his future comrades and enemies during this time—including William Tecumseh Sherman, Braxton Bragg, Jubal Early, and George Meade. While Beauregard graduated second in his class in 1838 and Anderson began to write the manual Instruction for Field Artillery, Horse and Foot, the two men did not cross paths again until the spring of 1861. Major Anderson, now assigned the command of Fort Sumter, faced his Beauregard across Charleston Harbor during the bombardment of April 12. After a 34-hour bombardment, Anderson surrendered the fort to his old pupil.

Fact #5: Charleston endured a severe fire in 1861, from which it struggled to recover for the duration of the war.

Around 10:00 p.m. on December 11, 1861, residents of Charleston noticed flames appear in three places almost simultaneously. The Charleston Mercury reported the first fire began at the Russell & Co. Sash and Blind factory, but others believed it began at Cameron & Co. Machine Shops on the other side of the street. Within an hour, the fire spread across the city—eventually engulfing almost all buildings on Meeting Street. The following day, Charleston awoke to ruins. The fire burned across 164 acres of the city, destroying 600 buildings – among those some of the city’s most iconic, including the Cathedral of Saint John and Saint Finbar, the Circular Congregational Church, and South Carolina Institute Hall where delegates declared secession nearly a year earlier. Though the fire’s origin remained mysterious, former slave Amos Gadsden claimed it started from a military hot air balloon while Union and Confederate troops camped around the city.

Fact #6: The first submarine to successfully sink a warship did so in Charleston Harbor in 1864.

Constructed in Mobile, Alabama, the vessel H.L. Hunley originated as a Confederate answer to the construction of a Union submarine known as the USS Alligator. By 1863, Hunley was ready for a demonstration. As the Confederates prepared for a siege after the fall of Fort Wagner, they resorted to some drastic measures to break the harbor free of Union occupation. In August 1863, H.L. Hunley arrived by rail in Charleston and entered service in the Confederate Navy. After several failed demonstrations in 1863 – in which the vessel’s inventor and namesake, Horace Lawson Hunley, was killed – Hunley now faced its first and final test against the United States Navy. On February 17, 1864, the submarine attacked the USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor. Though it marked the first successful submarine attack in history, Hunley mysteriously sank along with the Housatonic, resulting in the death of all 8 of her crew. Lost underwater until 1995, Hunley was raised in 2000 and is now on display in Charleston at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center.

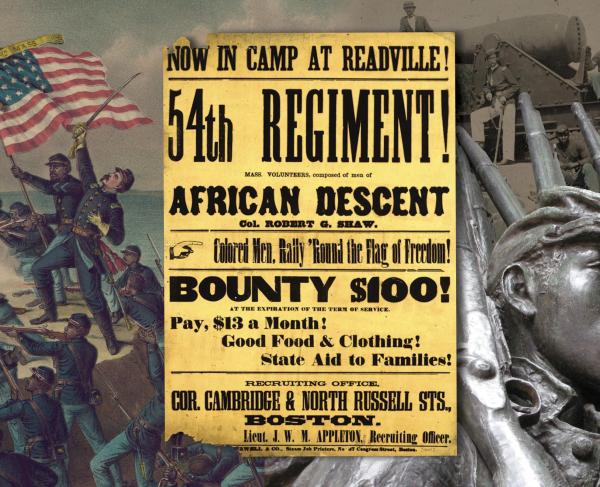

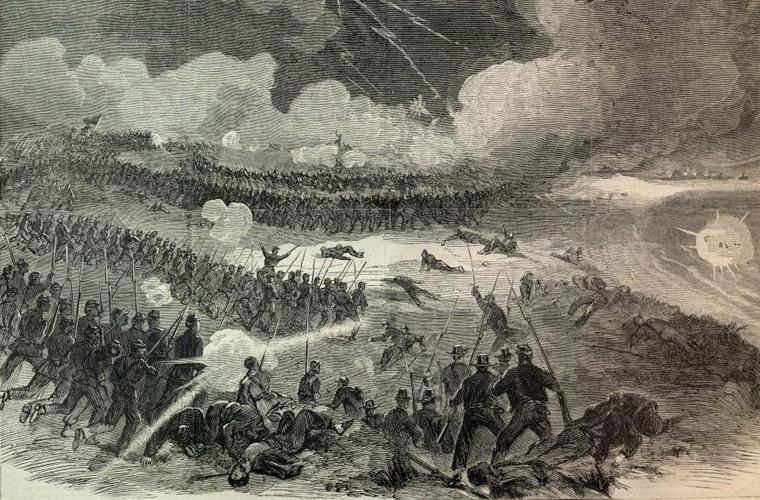

Fact #7: The assault on Fort Wagner was part of a Union campaign to capture Charleston in 1863.

The 1989 film Glory depicts the 54th Massachusetts assault on Fort Wagner on the night of July 18, 1863. This was part of a larger offensive by the Union Army and Navy to capture Charleston. After an unsuccessful naval bombardment of the city’s fortifications, Union General Quincy Adams Gilmore, commander of the Department of the South, turned his attention to Fort Wagner on Morris Island, which guarded the entrance to the harbor from a southwesterly approach. On July 10, two columns of Union infantry assaulted the fort but to no avail. On July 18, the Union reprised their attack in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, in which the 54th Massachusetts Infantry famously took part. The assault once again ended in failure and heavy casualties for the Union. However, the Confederates abandoned Fort Wagner in September, allowing the Federals to besiege Charleston. Union seizure of Morris Island allowed the army and navy to bombard Fort Sumter, and it was subsequently reduced to rubble by Union guns over the course of nearly two more years.

Fact #8: Before the Confederates evacuated Charleston, they set fire to the city.

As General William Tecumseh Sherman’s armies entered South Carolina in 1865, General P.G.T. Beauregard ordered the evacuation of Charleston on February 15. However, before the Confederates fled, they set fire to warehouses of cotton, destroyed artillery and equipment, and exploding munitions—further destroying an already damaged city. Confederate President Jefferson Davis remarked in 1863 that the city ought to be reduced to a “heap of ruins” rather than surrender. Now that was a reality. Charleston’s tragedies multiplied when a store of gunpowder detonated near the North Eastern Railroad depot, killing 150 people and injuring an additional 250 civilian men and women—all were looking for food inside.

Fact #9: After Charleston’s surrender in 1865, U.S.C.T. soldiers were among the first to enter the city.

Three days after Confederate forces evacuated Charleston, the city's mayor surrendered the city to General Alexander Schimmelfennig at 9:00 am on February 18, 1865. Schimmelfennig, who received allegations of cowardice at Gettysburg, now became the conqueror of Charleston, the birthplace of secession—a prize long sought by Union commanders. However, Schimmelfennig soon developed tuberculosis from the arid climate and succumbed to his illness later that year. Among the first Union soldiers to enter the city with him were the 21st Infantry Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops and the 55th Massachusetts infantry, another Black regiment. As the regiments marched into Charleston, they sang “John Brown’s Body”.

Fact #10: In 1865, Robert Anderson raised the American flag over Fort Sumter exactly four years to the day that he evacuated the fort in 1861.

With Charleston’s capture in February 1865 and the war’s imminent end, President Abraham Lincoln lobbied for a ceremony at Fort Sumter commemorating the garrison’s fall and celebrating the city’s recapturing. He chose April 14, the fourth anniversary of Major Robert Anderson’s evacuation of the fort. Lincoln was invited to attend the ceremony, but General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and the fall of Richmond compelled the president to remain in Washington. On the day of the ceremony, hundreds flocked to the fort to witness the momentous occasion. Robert Anderson, now a major general, raised the Sumter flag once more over the rubble. Abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Robert Smalls attended the ceremonies, along with Henry Ward Beecher (the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe) who delivered the keynote address. Lincoln’s assassination later that evening overshadowed newspaper coverage of the event.

Related Battles

685

204