10 Facts: Tom's Brook

Learn more about the historical significance of the Battle of Tom's Brook, fought on October 9, 1864. It was here at Tom's Brook, that the Union cavalry forces won their most decisive victory in the Eastern Theater.

Fact #1: Tom’s Brook is widely considered to be the most decisive Union cavalry victory in the Eastern Theater

Throughout much of the American Civil War, the Confederate cavalry forces in the Eastern Theater out-fought and out-classed their Union counterparts. Led by aggressive and talented leaders like J.E.B. Stuart, Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, John Mosby, “Grumble” Jones, and others, Confederate cavalrymen racked up victory after victory. But by mid-1864, a reinvigorated Federal cavalry arm, led by new, young, and aggressive commanders like Phil Sheridan, George Custer, Wesley Merritt, and David McM. Gregg, proved to be the superior battlefield force. In the Shenandoah Valley, Sheridan’s cavalry was a decisive force at Third Winchester and Cedar Creek. At Tom’s Brook, the Union cavalry produced its most complete and decisive victory of the Civil War.

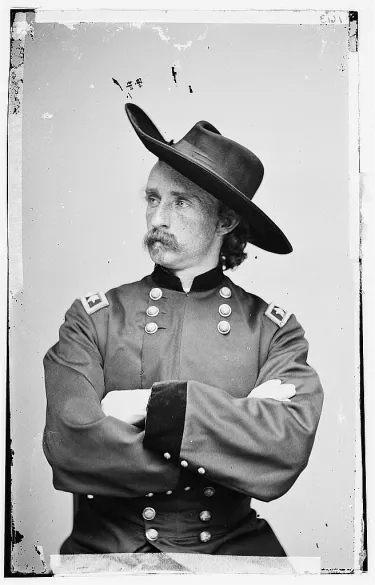

Fact #2: Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser (CSA) and Brig. Gen. George Custer (USA), both commanding divisions at Tom’s Brook, were West Point classmates and close friends

While at West Point, Tom Rosser and George Custer were roommates and close friends. Custer would call Rosser by his nickname “Tex” and “Tex” would call Custer “Fanny.” With Texas’s decision to secede from the Union in April 1861, Rosser quit West Point just a few weeks prior to his expected graduation. By the Battle of Tom’s Brook, Custer and his old friend Tom Rosser had met on many a battlefield.

These young, aggressive cavalry generals were keen to continue their West Point rivalry on the battlefield. Rosser, taking note of Custer’s arrival on the battlefield, reportedly shouted “[there’s] General Custer [that] the Yanks are so proud of, and I intend to give him the best whipping today that he ever got.” Unfortunately for Rosser, the Federal cavalry would decimate their Confederate opponents and Custer, who had captured his good friend’s headquarters wagon, later pranced around in “Tex’s” gray uniform coat after the battle.

Fact #3: Tom’s Brook was born of Sheridan’s desire to end Confederate harassment of his burning campaign in the Shenandoah Valley

On October 5, 1864, Phil Sheridan began his campaign of destruction in the Shenandoah Valley. Determined to destroy, once and for all, the agricultural potential of the Shenandoah, Sheridan had ordered his cavalry to burn and destroy mills, barns, and other agricultural stocks in their possession. This widespread destruction was quickly labeled “The Burning.” According to historian William Miller, “the emotional impact of The Burning on Rosser and his men cannot be overestimated.” Many of the Confederate horsemen were from the Shenandoah and were apoplectic at witnessing the destruction of their farms and homesteads.

Eager to stop this destruction, Confederate cavalry had been aggressively attacking Union detachments. This continual harassment of the Union operations incensed Phil Sheridan who then ordered that an attack be mounted that would drive off the Confederate cavalry. It was this order that led to the Battle of Tom’s Brook.

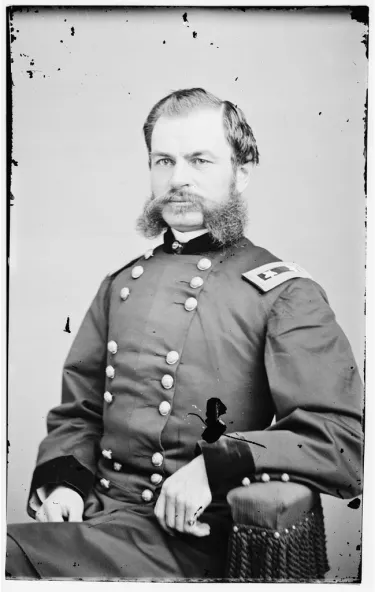

Fact #4: Sheridan was very displeased with his cavalry chief and ordered him to attack the next morning

Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, overall commander of the Union forces in the Shenandoah during the Fall of 1864, was already none too pleased with his cavalry commander, Alfred Thomas Archimedes Torbert. Torbert had already fallen into Sheridan’s doghouse after his lackluster performance at Fisher’s Hill. Sheridan, who had already fired other senior cavalry officers for their lack of aggressiveness, wrote to Torbert, telling him “I want General Merritt to turn on them [the Confederates] and follow them with either the whole or such portion of his force as he may deem necessary. This will be done to-day.” Later, Sheridan would write in his memoirs that “I told Torbert I expected him either to give Rosser a drubbing the next morning or get whipped himself.”

Fact #5: Despite being heavily outnumbered, Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser was convinced that he would prevail over the Yankee horsemen

The Confederate cavalry divisions in the Shenandoah Valley were fairly worn out by the time of Tom’s Brook. Confederate forces at Tom’s Brook numbered maybe 3,500. Lomax’s division, one of two at Tom’s Brook, only possessed 800 cavalrymen. Opposing them were the 9,000 Federal cavalrymen in Alfred Torbert’s three divisions. Despite this great numerical disadvantage, Maj. Gen. Thomas Lafayette Rosser stated that “I’ll drive them into Strasburg by 10 O’Clock.”

Fact #6: Prior to leading his charge against Rosser’s Confederates, George Custer rode to the front of his line and saluted his foe

Looking through his field glasses at the Confederate positions atop Spiker’s Hill, George Custer noticed his old West Point friend, Thomas L. Rosser. Ever the showman, Custer moved out in front of his lines and made a sweeping, grandiose bow in the Confederate’s direction. Widely reported in the Union press, several sketches of this action were circulated in the North. In James E. Taylor’s postwar memoir, he described Custer’s salute as something “like the action of a Knight in the Lists.”

Fact #7: Lomax’s cavalry division was very poorly armed

It is interesting to compare the two Confederate cavalry divisions at Tom’s Brook. Rosser’s “Laurel Brigade” was not only larger, but carried a variety of weapons, including Sharps carbines, Burnside carbines, Colt revolvers, sabers, and state of the art Henry repeating rifles. By contrast, Lunsford Lomax’s command was very poorly armed. Lomax’s cavalrymen were generally equipped with infantry rifles that were too long and unwieldy to fire on horseback. Lomax admitted later that he could not order a mounted charge since his men had “not a saber or pistol in the command.” Lomax’s men confronted a Union cavalry force that was carrying modern Spencer repeating carbines and other cutting edge weaponry.

Fact #8: The Union victory at Tom’s Brook led to an aggressive pursuit called “The Woodstock Races”

Despite putting up a brisk fire, the heavily outnumbered Confederate cavalry forces at Tom’s Brook were soon flanked and overwhelmed by the superior Federal attackers. As the Confederate lines wavered and were flanked, many a Confederate cavalryman broke and headed for the rear. Intent on saving themselves at all costs, the Confederate horsemen remounted and rode away at high speed. Looking to deliver a knockout blow, the aggressive Federal cavalry forces engaged in an active pursuit that was later called “The Woodstock Races.” The open ground south of Tom’s Brook provided little cover for the small Confederate rear guard efforts and gave the Yankee horsemen ideal terrain in which to gallop after their enemies.

Fact #9: Tom’s Brook is considered to be a prime example of the rise of the “hybrid cavalryman”

For much of the Civil War, cavalrymen were used extensively as scouts and light combatants. Most cavalry units were just not well equipped to stop Civil War infantry units. Mounted, they were vulnerable to rifle and artillery fire. On foot, most early war cavalrymen carried short, single-shot carbines, pistols, and sabers that were no match for Enfield or Springfield rifle equipped infantrymen. Choosing mobility over firepower was the tradeoff that all cavalry forces made prior to 1864. But with the arrival of modern repeating carbines, especially the Spencer, late-war cavalrymen could actually be quite effective in the dismounted role. As such, Tom’s Brook is one of the clear examples of the rise of the “hybrid cavalryman” – one who was a capable fighter both mounted and dismounted.

Fact #10: After Tom’s Brook, Confederate cavalry was never able to muster much of a challenge to the Federal cavalry

The Union victory at Tom’s Brook was an unmitigated disaster for the Confederate cavalry arm in the Eastern Theater. While accurate casualty figures are hard to come by, Sheridan reported that he had captured around 330 prisoners at Tom’s Brook. Merritt reported capturing 43 ordnance wagons, five artillery pieces, and countless other Confederate stores. Custer’s division had captured six artillery pieces, divisional ordnance wagons, ambulances, wagon trains, and the headquarters wagons for Tom Rosser and Lunsford Lomax. Union losses at Tom’s Brook, as stated by Torbert, “will not exceed sixty killed and wounded.” In his exultant report back to Sheridan, Alfred Torbert would write that “there could hardly have been a more complete victory and rout. The cavalry totally covered themselves with glory…” Witnessing the total ascendancy of the Federal cavalry in this theater, Jubal Early wrote Robert E. Lee on October 9, 1864 “that the enemy’s cavalry is so much superior to ours, both in numbers and equipment….and it is impossible for ours to compete with his.”

Learn More: Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley Campaign