Fort Sumter Ablaze

“Everybody seems to be getting excited, & some even frightened, in anticipation of what may happen in the attempt of some misguided scoundrels, who, it is said, intend to prevent, by force, the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as President of the U.S.” wrote Benjamin Brown French on January 1, 1861. This businessman and political officeholder’s words echoed many of the feelings and concerns that Americans had as the new year dawned. 1861 would be a year of excitement, fright, force and anticipation with a divided country believing the others were the “misguided” ones in the conflict.

In November 1860, Abraham Lincoln—a lawyer, former congressman from Illinois and nominee of the Republican Party—won the presidential election. Three Democratic Party candidates had split that party’s vote, giving Lincoln a majority of the total votes. Acting on previous threats if the Republican candidate won, southern states considered secession. South Carolina led the way on December 20, 1860, declaring itself out the union and making moves to form a separate nation. Other southern states prepared for secession conventions and started seizing federal property within their states.

January 1861 found President James Buchanan floundering to lead while Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana all adopted Ordinances of Secession. The Crittenden Compromise failed in the U.S. Senate on January 16, ending efforts to protect slavery in an effort to avoid civil war. Meanwhile, one week earlier, on January 9, cadets from The Citadel fired shots at the Star of the West; the ship attempted to bring supplies to the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor but had to turn back from the South Carolina harbor.

At the beginning of February 1861, delegates from the seceded states gathered and established a Confederate government with a provisional constitution and provisionally elected Jefferson Davis as president. This provisional government created a Peace Commission to try to avoid a war with the United States, but the efforts fell apart. Texas voted for secession on February 23, the same day that President-elect Lincoln arrived in Washington, D.C.

Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, becoming the 16th President of the United States. He concluded his First Inaugural Address appealing to the divided country: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” While hoping “better angels” would prevail, Lincoln also took action—meeting with his Cabinet on March 15 to discuss the situation at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. The federal fort in South Carolina had a stranded garrison, now surrounded by onshore rebel artillery and soldiers; food ran low, and the commander Major Robert Anderson waited for orders or supplies. Lincoln decided to send ships to Fort Sumter with supplies.

April 1861 saw the beginning of the American Civil War. Confederates in Charleston demanded the surrender of the garrison at Fort Sumter before the arrival of the ships with supplies. Major Anderson refused. On the morning of April 12, 1861, Confederates opened fire on Fort Sumter. After hours under attack, Anderson was forced to surrender; he and the garrison departed on April 14 and went north. Following the firing on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion. Responding to Lincoln’s call for troops, four more southern states drafted secession ordinances. Volunteers from Massachusetts traveling to Washington, D.C. were attacked by a pro-Confederate mob in Baltimore, Maryland, in what became known as the Pratt Street Riot. That same day—April 19—Lincoln ordered a blockade of all Southern ports; while it would take time for the blockade to become effective, the “Anaconda Plan” that would restrict the Confederacy’s use of seaports and focus on capturing rivers and other waterways. In both northern and southern states, men rushed to enlist in volunteer companies and regiments, and many worried the war would end before they had a chance to fight a battle.

Virginia, Arkansas and North Carolina formally declared themselves seceded in May 1861, and Tennessee would also join the Confederacy after a referendum in June—completed the eleven Confederate states. Meanwhile, Kentucky officially declared neutrality, refusing to join the Confederacy but also standing aloof of recruiting efforts for the Union. To help protect Washington D.C., United States troops occupied Baltimore, Maryland, and Alexandria, Virginia. The Confederates moved their capital from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, Virginia.

June 1861 found Confederation and Union volunteer soldiers trying to learn soldiering and sometimes engaging in small skirmishes. Military engagements were fought at various locations, including Fairfax Court House, Big Bethel and Vienna in Virginia and Boonville, Missouri.

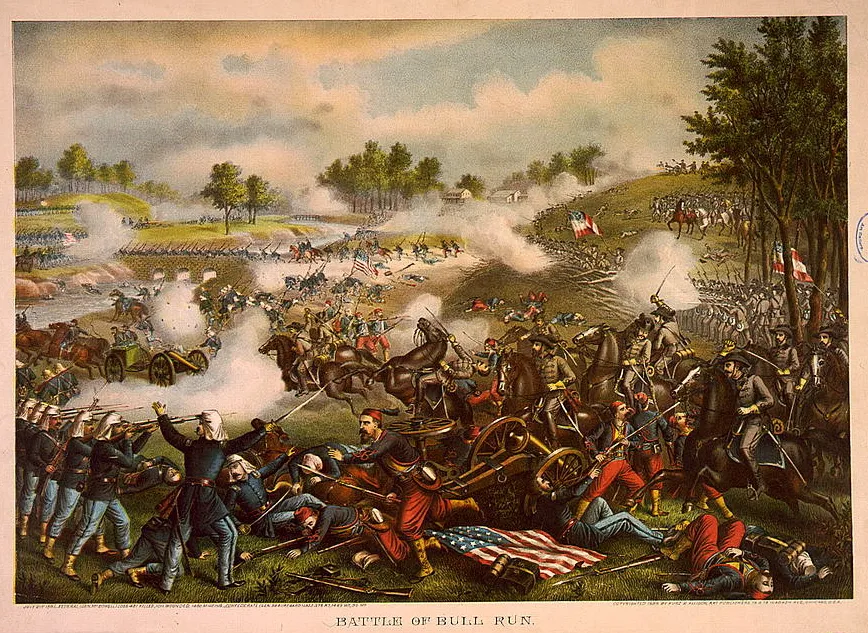

Skirmishes continued in July at Carthage, Missouri, and Laurel Hill and Rich Mountain in Virginia (now West Virginia). The first large battle of the Civil War occurred on July 21, 1861, near Bull Run and Manassas Junction. The battle ended with a Confederate victory, and the Union soldiers retreated to Washington. To the surprise of many at the time, the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run did not end the war. Instead, both sides started recruiting and training larger armies and preparing for a longer conflict.

Confederate forces won another battlefield victory in Missouri at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10, 1861. However, Union operations along North Carolina’s Outer Banks resulted in the capture of Confederate-held Forts Hatteras and Clark at the end of the month. August also brought political changes, including when Lincoln signed the Revenue Act of 1861 which created the first national income tax in American History. Union General John C. Fremont issued an edict which freed all slaves of Confederate sympathizers in Missouri, but he acted without authorization or higher approval; still it offered a glimpse of future political efforts and future changes for the Union’s war aim in the following years.

In September 1861, Kentucky’s proclaimed neutrality did not protect it from war. Confederates invaded the state and Union troops also moved to hold important cities in the Bluegrass State. Missouri also witnessed more skirmishes at Papinsville and Lexington. The Battles of Carinfex Ferry and Cheat Mountain were fought in West Virginia. In the far west, Fort Thorn in New Mexico Territory also saw a skirmish as the Civil War expanded and grew into a conflict that would affect more states and territories of the United States.

The first transcontinental telegraph line was completed in October 1861, increasing the speed of communication between states still in the Union on the east coast, west coast and Midwest. Smaller scale battles continued to be fought at Greenbrier River, West Virginia, Santa Rosa Island, Florida, Ball’s Bluff, Virginia and Springfield, Missouri.

November 1861 foreshadowed the coming new year and its large military campaigns. George McClellan became general-in-chief of the U.S. Army and continued organizing the Army of the Potomac and started preparing new strategies. Engagements were fought at Belmont, Missouri, Ivy Mountain, Kentucky, and Fort McRee in Florida. On the political front, the “Trent Affair” temporarily jeopardized international relations between the United States and Great Britain when Confederate emissaries traveling to Europe were forcible removed from the British vessel RMS Trent; the incident ended in December wen the United States released the Confederate emissaries.

In the final month of 1861, the U.S. Congress established the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. More skirmishes occurred Dayton and Hallsville Missouri. Native Americans took part in the Civil War conflict, and in December 1861 engagements were fought at Chusto-Talasah (Bird Creek) and at Chustenahlah in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

1861 was a tumultuous twelve months in American history. From Secession Winter to the first shots of the Civil War, numerous skirmishes and larger battles, the year ended with glimpses of Confederate success. The events of 1861 surprised many Americans in the north and south. They had expected the war to end within 90 days, but instead the conflict continued to escalate after the large battles at Manassas and Wilson’s Creek. Both Union and Confederate armies recruited and prepared for large-scale campaigns in the next year.

Further Reading:

- 1861: The Civil War Awakening by Adam Goodheart (Knopf Doubleday Publishing, 2012)

- The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War by Erik Larson (Crown Publisher, 2024)

- The First Battle of Manassas: An End to Innocence, July 18-21, 1861 by John J. Hennessy (Stackpole Books, 2015)

- Wilson's Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It by William Garrett Piston and Richard W. Hatcher III (The University of North Carolina Press, 2000)