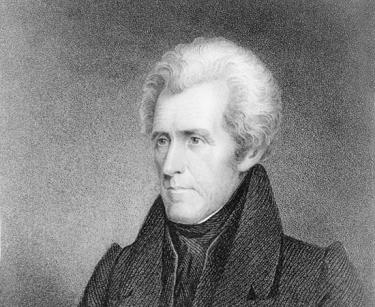

Andrew Jackson: Old Hickory - Adored and Despised

Just 29 years after the Treaty of Paris officially ended the Revolutionary War, our young nation found itself again at odds with Great Britain. Responding to an assortment of slights against American sovereignty that had caused repeated insult and economic damage, on June 18, 1812, Congress issued its first declaration of war.

On December 1, 1814, General Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans. The city was under threat of a British attack, and was one of the most vulnerable spots in America. It was a sparsely populated area, and the people were divided: The Anglo-Americans and Creoles did not trust each other, and much of the population were slaves who would likely join the British. It was a difficult and delicate situation that Jackson navigated skillfully, at least at first.

Jackson was lucky his opponents were the British. The Creoles, people of French, Spanish and/or African descent, but born in the Western Hemisphere, were not enthusiastic about being ruled by Anglo-American Protestants, but strongly preferred them to the British. Jackson made a good impression on several influential individuals, and often stayed with Jean Bernard de Marigny de Mandiville, a powerful politician known for his playboy lifestyle. He also made a grudging alliance with the buccaneer brothers Jean and Pierre Laffite, who provided Jackson with troops, scouts and, most importantly, gunpowder. Jean Humbert, who had served in the French Revolutionary army, was part of Jackson's staff. He had fled to New Orleans after it was discovered that he was having an affair with Pauline Bonaparte, the wife of his commanding officer, Charles Leclerc.

Jackson commanded a polyglot army - there were militias from Kentucky and Tennessee, as well as buccaneers, smugglers and Choctaw Indians in the ranks. In addition, there was the local Creole and Anglo-American militia. Much of the Creole militia was made up of free people of color who had taken part in military actions at least as far back as the Natchez War in 1729. By 1815, they were a major part of the city's defensive force. Jackson also had regular infantry and artillery on hand. All in all, his force had enthusiasm but not experience. While the British were not sending their finest regiments, quite a few were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars.

On December 14, the British crushed the small American fleet at Lake Borgne. Nine days later, they landed and took Jackson by surprise. Instead of panicking, Jackson attacked; losses were heavy, but the British were put off-balance, allowing Jackson to fall back to the Chalmette Line, five miles downriver from New Orleans. The British were in a dilemma: Swamps prevented a flanking movement against the Americans, and a formal siege was not possible given British logistics. Illness was also rampant in the British ranks.

On January 8, the British struck using a complicated plan that involved attacks on both sides of the Mississippi River. General Edward Pakenham, the British commander, attacked even as the fog lifted and uncovered his men. The assault was a disaster. In roughly 30 minutes, 2,000 British soldiers became casualties. Among the dead was Pakenham and his second in command, Samuel Gibbs. After the third in command, John Keane, was shot in the groin, command devolved to John Lambert, an uninspired soldier. Even though the attack on the west bank, which had been delayed, succeeded, Lambert withdrew. Efforts instead shifted to taking Fort St. Philip, the main strong point defending New Orleans from river assault. That siege also failed.

Unbeknownst to Jackson and Pakenham, however, the War of 1812 had essentially come to a close. Both sides had signed the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, although it still needed to be ratified by Congress. The victory in New Orleans brought to a close with a resounding victory a conflict that had seen numerous military disasters for the Americans. And, in earning a victory that ensured that New Orleans would not be sacked or set alight like the White House, Jackson became a national hero.

Before the battle, Jackson showed an impressive ability to forge alliances and an iron will that was a prerequisite for military victory. However, in the fighting's aftermath, Jackson showed his penchant for pettiness, pride and pointless pugnacity. Even as the British shifted to capture Mobile, first news of the treaty ending the war arrived. But Jackson was not sure of the situation. Martial law had been enforced since December 1, and Jackson —who had executed six militiamen for desertion —would not end martial law until he was certain the war was fully and formally concluded.

Louisiana state senator Louis Louaillier wrote an unsigned article in the Louisiana Courier that criticized Jackson for not returning civilian authority. In return, Jackson had him jailed. U.S. District Court judge Dominic A. Hall signed a writ of habeas corpus for the imprisoned senator, and for his trouble he, too, was jailed. A military court exonerated Louaillier, but Jackson ignored the verdict and kept the politician detained.

Hall was exiled from the city until martial law passed, at which point he returned and brought Jackson to court. Jackson's supporters, including many of the buccaneers, gathered inside. Dominique You, third in command to the Laffite brothers, said, "General, say the word and we pitch the judge and the bloody courthouse into the river:' Jackson refused to answer Hall's questions and was fined $1,000 for contempt of court.

When Jackson left the courthouse, he was surrounded by admirers and veterans of the battle. The buccaneers unhitched the horses on his wagon and pulled it down the street as people cheered and booed. Throughout his career, Jackson would inspire fear and hatred, but also devotion and love. Then, as now, Jackson did not inspire mildness.

The fine levied against Jackson left the city initially divided. But in time, he became a local hero for winning one of America's most lopsided victories. In 1856, a statue, cast after one erected near the White House in Washington, D.C., was erected in the Place d' Armes, which was renamed Jackson Square. In time, it became an iconic symbol of New Orleans, featured in books, brochures, posters and coasters. The courthouse where Jackson was fined was demolished after the Civil War, but the building on the site today is known as the Andrew Jackson Hotel.

Related Battles

62

2,034