Battle of Bentonville: Then & Now

The American Battlefield Trust sat down with historians Donny Taylor and Derrick Brown to discuss the Battle of Bentonville.

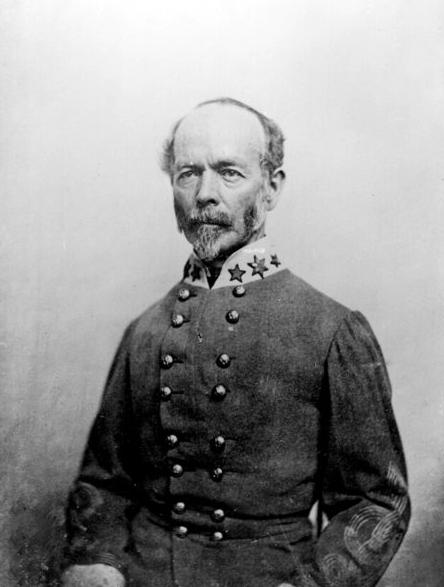

American Battlefield Trust: The Battle of Bentonville (March 19-21, 1865) would pit two of the Civil War’s most celebrated generals – William Tecumseh Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston – against one another. What were the strategic aims of these two generals at this time?

Donny Taylor & Derrick Brown: William Sherman was on the last leg of his nearly three month march north from Savannah, Georgia. Because of the Federal capture of Fort Fisher and Wilmington in January and February 1865, Sherman’s destination was Goldsboro, North Carolina. Goldsboro was strategically important because it was the location of the intersection of the Wilmington and Weldon and the Atlantic and North Carolina railroads. Sherman planned to rest, resupply, and reinforce his 60,000 man army at Goldsboro. He expected to reach the town without much serious opposition. From Goldsboro, his large well supplied army could march to Grant’s aid at Petersburg or move west to capture Raleigh.

Joseph Johnston had a much more difficult task than Sherman. Johnston was ordered by Robert E. Lee to consolidate all Confederate troops in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina into an army, and to somehow keep Sherman from linking up with Grant at Petersburg. Fortunately for Johnston, the remnants of the Army of Tennessee recouping from their disastrous assaults at Franklin and Nashville were also placed under Johnston’s command. By combining the Army of Tennessee, the Department of North Carolina, and heavy artillery garrison troops from captured or abandoned coastal forts, Johnston was able to piece together a 20,000 man army. This rag-tag army was not strong enough to defeat Sherman’s much larger force, but it could perhaps engage a portion of the Federal army while it was on the march.

I know that Robert E. Lee had been pushing Johnston to attack Sherman’s forces in North Carolina. Why did Johnston choose Bentonville as the place to attack Sherman?

DT & DB: It was not clearly evident to Johnston that Sherman’s goal was Goldsboro until he learned this information from prisoners captured at the battle of Averasboro (March 15-16, 1865). Johnston’s point of consolidation was Smithfield, and from this town he could place his small army along the Old Goldsboro Rd. at Bentonsville (only in the 20th Century did it become Bentonville possibly as a result of the battle being misnamed), which was the necessary route of march for Sherman’s left wing. Sherman’s army had been split into two separate wings to allow the army to travel over separate roads therefore speeding up the march. Like so many other places that became infamous during the Civil War, Bentonville just happened to be a spot on a map where the armies clashed. The village itself was of very little strategic importance.

It’s remarkable to think that Sherman’s numerically superior force could have been put at such risk. Did Sherman under-estimate Johnston and the Army of Tennessee at this late stage of the war?

DT & DB: Sherman was probably justified in his confidence as he marched through North Carolina because there had been no serious Confederate opposition to his army since it left Georgia. Even though Sherman respected Johnston (in his memoirs Sherman called Johnston his “special antagonist”), he did not expect that the Confederate commander could form an army in time to prevent the Federals from reaching Goldsboro. There was never any chance that Joe Johnston was going to be able to fight a successful offensive battle against the full weight of Sherman’s much larger force at this point in the war. Therefore Sherman and Johnston knew that the Confederate’s only hope was to defeat a portion of Sherman’s force, then wheel and fight the rest of the Union army. Though this plan sounds good on paper, both commanders knew it was a long shot at best. By March 18th, Sherman was so confident of his command safely reaching Goldsboro, that he departed the left which was closest to Johnston’s quickly consolidating army, to coordinate the right wing’s meet up with John M. Schofield’s and Alfred H. Terry’s Union armies marching from New Bern and Wilmington respectively.

On the first day of the battle, Johnston unleashed a powerful assault against the Union Left Wing. This assault has been called "The Last Grand Charge of the Army of Tennessee." How close did this attack come to succeeding and why did it ultimately fail?

DT & DB: "The Last Grand Charge of the Army of Tennessee" was at least initially successful in knocking Carlin’s XIV Corps division out of the fight on March 19th. Unfortunately for the Confederates, this charge by the veterans of so many western theatre battles was not strong enough to rout the entire XIV Corps. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Broadfoot commanding the 1st NC Junior Reserves described the attack as "gallantly done, but it was painful to see how close their battle flags were together, regiments being scarcely larger than companies and division(s) not much larger than a regiment should be." The Army of Tennessee’s assault might have been more successful in dislodging the XIV Corps and lead elements of the XX Corps if its assault had been better coordinated with Braxton Bragg’s attack below the Old Goldsboro Road. Bragg’s insistence on reinforcements before he would attack prevented the Confederates from launching a general assault. This more than anything else prevented the Confederates from winning an overwhelming victory on the first day of the battle.

Did terrain play a significant role in affecting the "Last Grand Charge"?

DT & DB: In the opening stages of the battle, General Carlin launching a probing attack north and east across a water filled ravine on the Cole Plantation. After meeting stiff resistance from the Army of Tennessee (although Carlin did not know it was the AOT at the time because most of the Confederate force was hidden in the piney woods) Carlin’s force retreated back to the ravine and entrenched on the Confederate side instead of crossing back over and entrenching on the safer side. The full weight of the "Last Grand Charge" fell upon Carlin’s Division whose troopers prudently tried to get back across the ravine every man for himself. Although this ravine aided in the Confederate rout of Carlin’s Division, it also slowed the "Last Grand Charge," because the now disorganized Confederate units had to cross the ravine and attack out of the other side. This delay allowed lead elements of the XX Corps to form a new defensive line along the Old Goldsboro Road.

After the failure to break the Union line on the first day, why did Johnston and his much smaller army stay at Bentonville?

DT & DB: Once his attacks on the first day were not successful, the obvious choice for Johnston was to retreat. After all, the right wing of Sherman’s army was on the battlefield in full force by the second day. Considering that Johnston was known as a cautious commander at best, it seems curious that he would stay on the battlefield confronted by what seemed like insurmountable odds. In his memoirs the Confederate commander offered two reasons as to why he remained on the field after the actions on March 19th. First was the practical duty of removing his wounded from the battlefield to his headquarters at Smithfield. Johnston also mentioned the improved morale of his army after the fight of the 19th. Retreating immediately from the battlefield may have jeopardized these gains in the soldiers’ morale. His decision to stay and confront Sherman’s army almost proved disastrous for Johnston and his command.

The Union assault against Johnston’s lines, Mower’s Charge, on the third day of the battle, managed to overrun Johnston’s headquarters. What prevented this attack from completely overwhelming the Army of Tennessee?

DT & DB: After the battle of March 19th General Johnston’s strategy was no longer one of offence but one of defense. At this time he began planning and all out defense of Mill Creek Bridge realizing that it was his only exit from the battlefield and had to be defended at all cost. Once General Mower’s attack began General Johnston needed to move reinforcements to the left flank to help hold that position and started moving elements of William J. Hardee’s Corps from the right flank to the left flank. About the same time reinforcements from Smithfield under the command of General Frank Cheatham consisting of Brown’s Division and Lowery’s Brigade of Patrick R. Cleburne’s Division totaling about 1,000 men arrived at the right place and right time for the desperate Confederates. These reinforcements, a counterattack by General Hardee’s Corps, and the fact that General Mower was ordered not bring on a general engagement, saved Mill Creek Bridge and the Confederate line of retreat.

Donny, you have been a student of this battle for 10 years. What aspects of this battle interest you the most?

DT: The most interesting aspect to me is the first day March 19, 1865. General Carlin deploying to clear the Goldsboro Road and later realizing that the Army of Tennessee was in his front and eventually being driven ingloriously from the field. The fighting below the Goldsboro Road in which Federal General James Morgan faced General Braxton Bragg’s Department of North Carolina. General Morgan stopped Bragg’s attack, jumping to the opposite side of his trench to fight Confederate General D. H. Hill which had gotten in his rear, then Hill was in turn was driven out by Federal troops under the command of General Cosgwell earning this hotly contested area the nickname "The Bullpen." From here the fight progressed to the Morris Farm where Confederate General Bate made several attacks across open ground into massed Federal infantry and twenty one cannon that had been massed for the defense in this area. The battle of 19th of March had enough movement, desperate attacks in difficult terrain, and lost opportunities to hold any Civil War buff’s interest.

As the Historic Site Manager for the battlefield you have done much to improve the visitor experience at Bentonville. What can a visitor see and do at this site today?

DT: Today in our Visitor Center visitors to Bentonville Battlefield have the opportunity to see a fifteen minute audio visual program that summarizes the war and the history Bentonville played in this great conflict. Also in the Visitor Center there are exhibits that begin with General Sherman’s departure from Atlanta and continue through the Carolina’s Campaign which includes Fort Fisher, Fort Anderson, Monroe’s Crossroads, Fayetteville, Wyse Fork, Averasboro and Bentonville. Other exhibits include artifacts from the battle and a fiber optic map of the March 19th Battle.

Also on site is the circa 1855 farm home of John Harper which was used as XIV Corps Field Hospital. This home is interpreted as a field hospital on the first floor and as quarters for the Harper Family, who remained at the home, on the second floor. Two support structures, although not the original buildings are interpreted as a kitchen and slave quarters.

Across from the Visitor Center is the Harper Family Cemetery and the graves of twenty Confederate soldiers that died in the care of the Harper Family after the battle. Adjacent to the cemetery is a walking trail with reproduction earthworks, a reproduction 12 pounder Napoleon cannon and two panels interpreting the naval stores industry, and authentic Michigan Engineers earthwork which are viewable from the walking trail.

Once your visit to the Visitor Center is complete you can take a ten mile diving tour of the battlefield, stopping at any of four interpretive tour stops. These tour stops have interpretive panels that include battle maps, text, photos and quotes from soldiers that fought in particular area.

Over the past 10 years a great deal of battlefield land has been preserved at Bentonville. How have these acquisitions helped to improve the battlefield experience at Bentonville?

DT & DB: Property purchased at Bentonville has eased pressure from development on key portions of the battlefield. We now have in possession about 85% to 90% of the March 19th, battlefield, important areas of the March 20th battlefield including existing earthworks, and finally major acreage covering the area of Mower’s Charge and Mill Creek Bridge on March 21, 1865.

The purchase of these properties allowed us to construct four tour stops and install interpretive signage. These interpretive areas are used by visitors in general, Civil War enthusiasts, tour groups and military staff rides.

What big projects do you have underway at the Bentonville Battlefield?

DT & DB: Future plans for Bentonville include continued battlefield preservation, installation of more tour stops, installation of headstones for the twenty Confederate Soldiers buried near the Harper Cemetery, a ten year development study and hopefully a new museum and maintenance complex. Some of the goals are attainable in the near future and while others may be several years down the road.

Being able to work with the Civil War Trust in the purchase of properties over the past eight years has been a pleasure and salvation for this battlefield. I feel we are years ahead of the development curve in this part of Johnston County and the Trust, its members, and other supporting grant organizations have made that possible.

The North Carolina Historic Sites website for the Bentonville Battlefield is filled with a lot of great information about the battle and the park. Has the website become an important part of the park’s offerings?

DT & DB: We constantly get inquiries from private individuals as well as military groups needing information on the battle. The website is a wealth of knowledge and contains almost any information anyone would need about the battle, certainly more than we would be able to send to an individual. Our staff at Bentonville is small and by having all the information on the website it saves numerous hours of staff time.

Donny Taylor and Derrick Brown are respectively the Site Manager and Assistant Manager for the Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...

Related Battles

1,527

2,606