The Battle of Freeman's Farm: September 19, 1777

The first battle of Saratoga, also known as the Battle of Freeman’s Farm, occurred on September 19, 1777. This bloody action was the culmination of months of maneuvering and combat that began that spring. The British were hoping that three different invasion forces would advance towards Albany, New York from the north, south, and west. By capturing Albany, the British would effectively cut off the New England states from the rest. However, the southern advance never truly materialized, and the western advance was driven back at Fort Stanwix and Oriskany. The only column left was the army under the command of British General John Burgoyne.

Burgoyne had moved his army of 7,000 British redcoats, German auxiliaries, Loyalists, and Native American allies out of Canada in June of 1777. In early July, Burgoyne captured Fort Ticonderoga and defeated a patriot rearguard at Hubbardton, Vermont. Despite the fact the Americans lost the battle, the battle at Hubbardton allowed the main American army to escape from Burgoyne.

Burgoyne marched his army overland towards Fort Edward. American General Philip Schuyler slowed the British march by felling trees and destroying bridges. From Fort Anne to Fort Edward, the British had to cut a road through the wilderness. Burgoyne’s march ended up taking nearly a month.

In early August, German Lieutenant Colonel Friedreich Baum took a force of 800 men and foraged for more horses. Baum though was defeated by Colonel John Stark and 1,500 militiamen on August 16, 1777, at the Battle of Bennington. This proved to be a costly error for Burgoyne, and he lost nearly 1,000 men as a result. Additionally, many of the Native American allies in Burgoyne’s army began to leave following the defeat at Bennington.

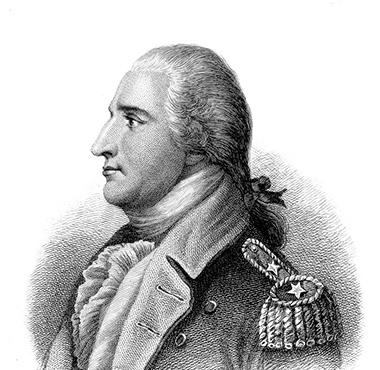

In the American camp in August, Congress replaced General Philip Schuyler with General Horatio Gates. His army numbered about 7,000 men and was encamped on a bluff on the west side of the Hudson River just south of Saratoga, New York. This bluff, known as Bemis Heights, was a strong position and fortified by the Americans. The American fortifications had been laid out by Polish engineer Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko. The American right flank was anchored on the Hudson River. On Gates’ left flank he placed General Benedict Arnold with 2,000 men including Colonel Daniel Morgan’s riflemen. Gates’ most vulnerable position was his left flank. It would be important that the Americans prevent Burgoyne from turning his left flank. Gates remained in his position and awaited Burgoyne to attack.

On September 13 and 14, 1777, Burgoyne and his now 6,000-man army crossed to the west side of the Hudson and began marching south toward the American army’s position. By September 18, Burgoyne was camped just four miles north of the American Army. With very few scouts he was unsure of how to exactly proceed but knew Gates and a large army was encamped to his front. Burgoyne decided he would perform a reconnaissance in force to feel out Gates’ army and if possible, to turn Gates’ left flank. On the morning of September 19, Burgoyne sent out three columns of troops heading south towards Bemis Heights. Meanwhile, in the American camp, Arnold begged to move his troops forward to engage the British. Gates relented and sent forward Arnold and Daniel Morgan’s troops north.

The two armies converged in a clearing on John Freeman’s Farm a little afternoon. Morgan’s Corps in the lead of the American line fired into the British scouts and charged into their lines. The British were sent backwards, but British reinforcements quickly came up and drove Morgan’s men back to the south end Freeman’s Farm. Those reinforcements were the center column of Burgoyne’s force, the brigade of General James Inglis Hamilton.

Hamilton moved his army into battle formation and marched his British regulars forward to the southern end of the farm. Gates dispatched New Hampshire soldiers from General Enoch Poor’s brigade to help Morgan’s men. The two sides engaged in a heated firefight on the southern end of the farm. In the center of Hamilton’s line was the 62nd Regiment of Foot, which would suffer the brunt of the violence that day. As the 62nd stood and fired towards the Americans concealed in the woods, they realized their volley fire was ineffectual, and the American fire directed towards them was having devastating effect. British artillery came up to support the British, but they too were being picked off by American riflemen and their cannonballs were doing more damage to the trees than to Arnold’s men. The commander of the 62nd Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel John Anstruther decided he would use the bayonet to drive the Americans back. His men charged into the woods after the Americans four different times, and each time the Americans fell back, only to reform and return to their original positions, taking out more and more British soldiers. As the hours progressed more British and American troops entered Freeman’s Farm and extended the lines, but neither side could gain the upper hand. As the brutal fighting raged, one British soldier described how “ground flowed with English and American blood.”

Meanwhile, Burgoyne’s right column, the brigade of General Simon Fraser began to engage New York Continentals on the American left flank. By 3:00 p.m. the fighting was raging all along Arnold’s line. At that time, Burgoyne’s final column on the extreme British left, under the command of Baron von Riedesel with mostly German troops were marching on towards Gates’ main position at Bemis Heights. As the fighting intensified at Freeman’s Farm, Riedesel halted and waited for orders on what he should do. As the sun was setting, he got orders to march some of his men to attack the American right flank. He immediately marched 700 men towards the vulnerable American flank.

Arnold returned to Bemis Heights to ask Gates for more reinforcements. Gates, fearing an attack on the main position refused to Arnold’s dismay. Riedesel’s men arrived at Freeman’s Farm and began firing into the American right flank. With darkness beginning to cover the field, with no more reinforcements, and with both flanks being pushed by larger numbers, Arnold’s men fell back towards Bemis Heights.

The day ended with the British holding Freeman’s Farm, but it had been an incredibly bloody affair. Nearly 600 British soldiers had been killed, wounded, or captured and more than 300 Americans had been killed, wounded or captured. One of the hardest hit regiments was the 62nd Regiment of Foot which lost more than half their strength, 210 men, in the fighting around Freeman’s Farm. While a British tactical victory, it had been a Pyrrhic victory. They had lost more men and had been halted on their attempt to strike at Gates’ main force on Bemis Heights. The British remained at Freeman’s Farm and began to fortify their position just a mile and a half from Bemis Heights. The two sides remained encamped in their respective positions for the next three weeks before fighting again at the Battle of Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777.

Further Reading:

-

Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War By: Richard Ketchum.

-

With Musket & Tomahawk Volume I: The Saratoga Campaign and the Wilderness War of 1777 By: Michael O. Logusz

-

The Compleat Victory: Saratoga and the American Revolution By: Kevin J. Weddle.

Related Battles

330

1,135