The Battle of Middleburg

The following is excepted from a larger article entitled "Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville" which first appeared in Gettysburg Magazine, Issue #43.

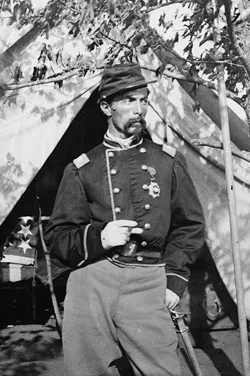

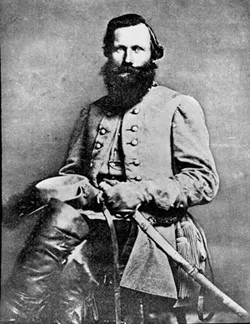

Early on the morning of June 17, 1863, as Brig. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick led his brigade of Federal cavalry out of Manassas Junction, he dispatched Col. Alfred N. Duffié to lead his regiment, the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, to Middleburg. He was to secure the town that evening, and link up with the brigade the following day after making an extended scout of Loudoun County. Passing through Thoroughfare Gap, Duffié’s troopers skirmished with elements of the 9th Virginia of Col. John Chambliss’ brigade but pressed on and continued north toward Middleburg, reaching the village about 4:00 p.m. Pushing up the road from White Plains (today known as The Plains) Duffié’s lead squadron engaged pickets from the 4th Virginia Cavalry and drove them back into the center of town. They arrived just as Confederate cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart and his staff were having lunch at a tavern in Middleburg. Having had almost no warning, General Stuart and his staff were forced to beat an embarrassing retreat to the west. As he escaped the immediate reach of the Federals, Stuart ordered Lt. Frank Robertson to tell Col. Thomas Munford, at Aldie, to withdraw his brigade to Rector's Cross Roads.

Having seized Middleburg with only a smattering of shots fired, Duffié knew that holding the town for the night would prove much more difficult. He knew that Chambliss’ brigade was shadowing him from the south and he soon learned of Munford’s passage through the town, earlier in the day, to the east. Still, he opted to follow the letter of his orders and set his men to barricading the five roads leading into the village, but then chose to man those barriers with only a small force of pickets. Duffié posted a stronger detachment, about sixty men, behind a wall lining The Plains road about 250 yards south of town, and then led the remainder of the regiment two miles farther south.

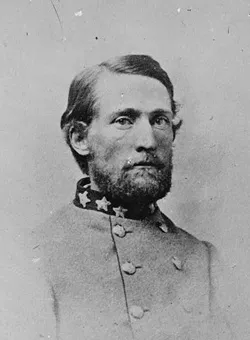

Along the road to Rector's Cross Roads Stuart met Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson and his Tarheels and immediately ordered them to attack and reclaim Middleburg. Charging down the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike, silhouetted by the still blazing sun as it settled behind the mountains, the troopers smashed into the barricades and sent the pickets fleeing south. After securing the town and sending scouts to check the other avenues of escape, the Carolinians, with Prussian Maj. Heros von Borcke at their head, charged down The Plains road and into Duffié’s ambush. Brought to a halt by a tree blocking the road, the Tarheels were lashed by a sheet of carbine and pistol fire along their left flank. Quickly falling back, they reformed in the gathering darkness and charged twice more, losing men each time with no result. After the third attempt they were ordered to attack on foot. Hearing this, the Yankees elected to pull back and search for their comrades in an area now swarming with gray-clad troopers. Unbeknownst to either side, Duffié’s men bedded down within yards of the 9th Virginia Cavalry.

At first light the next morning Federal scouts spied a Southern detail sent to gather corn and realized the predicament they faced. The Federals made only a brief attempt to force their way through the Southern line. With enemy troopers swarming all around his gallant band, Duffié ordered them to make their way to safety anyway they could. Their attempt at a breakout quickly degenerated into a rout and by early afternoon only Duffié and thirty-one officers and men had reached the Union lines. After the remaining fugitives made their way to safety, the grim toll became apparent: 6 killed, 9 wounded, and 210 men missing or captured.

On the night of June 17, 1863, Confederate partisan Maj. John S. Mosby captured two Federal officers carrying dispatches from Army commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to his cavalry chief, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton outlining the size and disposition of the Federal army as well as Pleasonton’s orders to his subordinates. Also mentioned was that Brig. Gen. Julius Stahel was leading a reconnaissance to Warrenton. In Mosby’s own words they had just captured the "open sesame to all of Hooker’s plans and secrets." By morning the documents were in Stuart’s hands. Soon a Confederate rider was racing south to notify Wade Hampton, then near Warrenton, to be prepared to meet Stahel, while along the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike Stuart prepared to blunt Pleasonton’s next thrust.

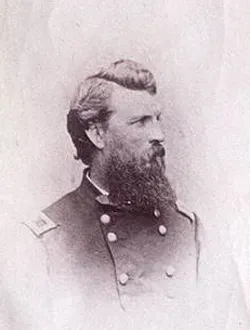

By late morning Col. John Irvin Gregg’s brigade was riding towards Middleburg, to make contact with Duffié and his 1st Rhode Island. The 16th Pennsylvania, supported by the 4th Pennsylvania and 10th New York, met the Southern pickets east of town and after a spirited skirmish pushed them west to their main line of resistance along Mount Defiance, a low ridge a mile west of town.

After Gregg’s men had taken possession of the village, they began to learn of the disaster that had befallen Duffié’s regiment. Several men of the regiment were released from temporary prisons within the town, others came out of hiding, and the dead of Robertson’s brigade were found laid out on a porch. Gregg’s brigade pushed a mile beyond the town until brought to a halt below Mount Defiance by Stuart’s battle line. Here the two sides sniped at each other until 3:00 p.m. when word arrived from Pleasonton for Gregg to withdraw toward Aldie, as he felt that Stuart was trying to draw his horse soldiers "on to their infantry."

With the exception of Duffié’s rout in the morning, the day was rather bloodless. During the day Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck had goaded Hooker by claiming, "Officers and citizens [in Pennsylvania] are on a big stampede. They are asking me why does not General Hooker tell where Lee’s army is; his is nearest it." The army chief of staff then continued: "There are numerous suppositions and theories, but all is yet mere conjecture. I only hope for positive information from your front." Thus Hooker was forced, in turn, to remind his cavalry chief, "your orders are to find out where the enemy is, if you have to lose men to do it." Or as Hooker's Chief of Staff Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield put it, "We cannot go boggling round until we know what we are going after."

On the afternoon of June 19, Pleasonton informed Butterfield that he had been told of Mosby’s capture of his officers , that he assumed they had been carrying important documents, and as a result "I have acted carefully." This may explain why he believed that he was being led into a trap and thus gave up the ground gained so easily on June 18 only to have to fight for it again the next day. Unfortunately, for the men in the ranks, it would be another bloody day in which nothing was easily gained.

Middleburg was remembered as a "very pretty village of tasteful white houses, standing on high ground, and intermingled with trees," but looming beyond it was the dominating ridge now known as Mount Defiance. Another soldier wrote that a "prominent feature of the landscape . . . were the stone fences," the same type of fence that had so materially aided the Southern defense at Aldie.

In position along the southern end of the ridge, in a thick section of woods, was Robertson’s brigade of Tarheels. At the very crest of the hill, guarding the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike and continuing along the northern extension of the ridge was Chambliss’ brigade. At the crest of the hill near a small blacksmith’s shop, the turnpike slices a deep cut through the ridge, and is guarded by stone walls on both sides that afforded Chambliss’ men protection as they fired down into the ranks of attacking troops. Supporting the cavalry were two batteries of horse artillery, commanded by Capts. Marcellus Moorman and William McGregor. For good measure one artillery piece was placed in the road itself, firing down the hill, but the Federals got a taste of what lay ahead long before they reached that position.

Colonel Gregg was again elected to lead the advance, supported by Kilpatrick’s battered brigade. Gregg had his men on the move by 6:00 a.m. with the 4th Pennsylvania and 10th New York in the lead. They covered the miles between Aldie and Middleburg easily until they reached the outskirts of the town. There they encountered a heavy force of skirmishers and were driven back. After reforming, and being joined by Col. John Robison’s 16th Pennsylvania, they outflanked the gray skirmishers and carried the village. Once through the town, Gregg sent the Pennsylvanians south and ordered them to advance on foot, supported by a squadron of the 1st Maine on horseback. Along the road he kept the remainder of the 1st Maine, now commanded by Lt. Col. Charles H. Smith, and the 10th New York, led by Maj. Mathew Avery, mounted. Gregg’s approach was slow, however, as he absorbed the daunting task ahead. Adding to his concern were the eight enemy cannon that brought his line under fire as soon as it cleared the town and scored an early success by blowing up a Federal limber.

To hasten Gregg's progress along the turnpike Pleasonton directed Buford to take his two brigades (Devin was still watching Thoroughfare Gap and Haymarket) to the north, cross Goose Creek, and attempt to flank the Southern position. Buford may have split his two brigades to cover more ground. His orders were to advance via the town of Union and he sent Gamble’s brigade up the Snickersville Turnpike. The Reserve Brigade may have followed Gamble but probably rode through Middleburg before attempting a flanking move. It would be late afternoon before either brigade saw any action heavier than skirmish fire.

As Gregg continued to ponder his options, his cousin and division commander, Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg, sent an aide forward to demand an explanation for the delay. The brigade commander asked that Kilpatrick be brought up to extend his line north of the pike and within a short time both the 2nd New York and 6th Ohio were extending a dismounted skirmish line south of Chambliss’ position. After they were positioned Colonel Gregg renewed the advance.

At the extreme southern end of the skirmish line, one mile south of the turnpike, the men of the Keystone State ran into a Southern strong-point around the brick walls of a small family cemetery, wherein lay the remains of George Washington Cocke. Col. William Doster termed the resistance at the cemetery "obstinate," with the men fighting behind the "grave stones and walls" before they drove the Tarheels back to the cover of the wood line. Moving alongside the 4th was Capt. Issac Ressler and the men of the 16th Pennsylvania. As he recalled the day’s events in his diary that night he boasted that he "Stormed across wheat field into woods. . . . FIRST CARBINE CHARGE. . . . I was in the first carbine charge ever known. Dangerous."

As the men cleared the wheatfield and entered the treeline, the fighting “was more of an Indian warfare than anything seen of late. Nearly all of the charges made were in woods where the enemy fought from behind trees, stone walls and natural rifle pits.” While the majority of the combatants were dismounted, Companies E and M of the 1st Maine, led by Capt. George M. Brown, charged into the woods on horseback.

Straight into the woods we dashed, met by a fierce volley from a body of dismounted cavalry . . . nearly through the belt of woods we pushed them . . . from tree to tree we pushed them. When the halt and rally was sounded both sides were glad to retire and reform. In three minutes we were upon them again. They were now beyond the woods behind a stone wall. Our charge was repulsed and as we retired they tried to reach their horses and reserves, but . . . Co. E to their left and rear and Co. M to the right and front, enveloped and captured them to a man.

One man’s action near the turnpike was recalled by men of both sides and was proof of the vicious nature of the battle. Orderly Sgt. Michael M. Logan of the 16th Pennsylvania

was on the dismounted skirmish line when it was attacked by the rebels mounted. The . . . sergeant, after fighting until his ammunition was exhausted, clubbed his carbine. Losing that, he threw stones until he fell exhausted from wounds and loss of blood.

When his comrades found him later he suffering from "several ugly sabre cuts on his head and three gunshots on his person." Lt. George Beale, of the 9th Virginia who was engaged in the mounted combat along the road, penned a similar account:

The hand-to-hand encounter that ensued between us and these men of Maine and Pennsylvania was sharp and bloody. One of them, I observed, who had been unhorsed, and had backed up against an oak . . . and having fired his last cartridge, was defending himself with rocks . . . until he fell from their pistol shots.

In the road and to the north the fighting was deadly and dramatic. North of the road the men of the 2nd New York and 6th Ohio pushed against the stone wall held by the 13th Virginia led by Maj. Joseph Gillette, while the first attack, in the road itself, was spearheaded by Maj. Stephen Boothby at the head of Companies C and G, 1st Maine Cavalry. At the crest of the hill Boothby saw a mass of Southern troopers crowded around the single cannon. After firing a volley with their carbines, Boothby ordered his men to draw their sabers as they charged up the slope. Taking fire from the enemy above them, they pursued a body of mounted gray horsemen who fled down the reverse slope and into the fields on the right of the road. Just then the 1st Maine were attacked by the 9th Virginia, which hit the Federal flank as it came by. The column wheeled about and headed back down the turnpike pursued by Col. Richard Beale's Virginians.

Lieutenant Beale remembered:

We took the gallop in platoons and struck the 1st Maine just as they surrounded the gun where a desperate struggle took place with the cannoneers. They began to retreat as we reached them. . . . We pursued them but a short distance before their heavy skirmish line on both the right and left of the pike checked us with their fire and the 10th [New York] hastened to their support.

After the Virginians drove the Federals off the hill, Stuart began pulling the guns off the crest and into position on the ridge above Kirk’s Branch , about a half mile to the west. To the south behind the woodline, Robertson’s Carolinians were falling back in the face of the Union attack. In an effort to rally those troops, Stuart and several of his staff, including Major von Borcke, Capt. William Blackford, and Lt. Frank Robertson, rode into the field through which the Tarheels were retreating. This knot of officers, led by Stuart and the conspicuous Prussian, immediately came under fire from the Federals as they emerged from the trees, and within minutes von Borcke was reeling in his saddle, staggered by a bullet in the neck. With difficulty Blackford and Robertson got him off the field as the last of the Tarheels rode off.

Below the hill, the tide of the 9th Virginia broke against Maj. Mathew Avery’s 10th New York. As the New Yorkers’ pistol and carbine fire drove Beale’s men back up the hill, Avery ordered Maj. John Kemper in pursuit with Companies F and I. Dropping their carbines and drawing their sabers, they charged up the hill where they received the last round fired by the cannon in the road. Kemper shouted for the men to make for the blacksmith shop, but the loss of both company commanders temporarily disorganized the column. Once they reached the crest they were confronted again by the 9th Virginia and this time it was the New Yorkers who fell back, being raked again by fire from the men behind the walls above them. Gregg had succeeded, however, in driving the 13th Virginia from their section of the wall, north of the road, and these men, as they reached their horses, may have joined the 9th Virginia in driving off Avery.

Waiting below the hill for Kemper’s return were the men of Companies B and D led by Maj. Alvah Waters. Kemper rode up to him and warned, “Don’t go into those woods, Waters; it’s a slaughter pen.” Kemper had taken about fifty men into his charge and reportedly returned with only five, yet the regiment listed losses of only twenty-six for the entire battle. Undoubtedly, a large number of his horses were killed near the crest, leaving many of his men afoot, and Company I did incur the majority of the casualties sustained by the regiment. The going would be easier for Waters, however, as the battle now reached a climax around the blacksmith’s shop.

Once the North Carolinians withdrew from their position in the woods the Federals, led by Capt. George Brown’s mounted contingent of the 1st Maine, were free to lend their weight to the battle along the turnpike. Near the back of the treeline Brown’s men struck a narrow farm lane that led back to the turnpike, immediately alongside the blacksmith’s shop. These troopers entered the turnpike shortly after the men of the 2nd North Carolina had been ordered to withdraw from their position around the shop, and just as Colonel Chambliss was preparing to lead a counter-charge against Waters’ squadron. The three columns met in the road around the shop with a clash of sabers, but there was no need for Stuart to continue the fight. With a second line now established to the west, Chambliss was ordered to disengage.

Stuart clearly understood that his mission in the Loudoun Valley was to prevent the Federal cavalry from penetrating the mountain passes of the Blue Ridge and locating the Confederate army. Thanks to the dispatch captured by John Mosby, he also understood the fog that Hooker was operating in as a result of not knowing for certain where Lee was and what his intentions were. Stuart was, therefore, determined to trade distance for time. In other words, he did not need to defeat Pleasonton on the field; he would let time carry the day. Having held up the Federals for the greater part of the day, a day in which they gained no more ground than that which they had held briefly the day before, Stuart fell back. Just as importantly, he had battered Gregg and Kilpatrick to such a degree that they were in no condition to follow. Dusk found his tired brigades only a half-mile west of the battlefield, but there was no time for congratulations as dust billowed up to the north near the hamlet of Millville along Goose Creek.

About 6:00 p.m. the Regulars, with the 2nd and 6th United States Cavalry regiments in the van,were splashing across Goose Creek at Millville. One unimpressed officer described the hamlet, which no longer exists, as being occupied by “the lowest class of white inhabitants . . . the poor devils whom public contempt in the South designates as White Trash.” As the Regulars rode past the hapless village, they came up on the unprotected flank of Stuart’s new line. Word of their approach reached Chambliss, literally in the nick of time, and two regiments were soon galloping for a hillcrest from which to block the advance.

A half-mile south of the ford and several hundred feet west of the road leading from Millville to the turnpike, a small knoll dominates the immediate area, including the northern end of Stuart’s new line. A wall, several hundred yards square enclosing a small field, crowns the crest of the knoll. It was to this point that men from both sides now raced, on foot, with the Federals gaining possession. Lt. Tattnall Paulding, 6th U.S. Cavalry, complained that the fire of his men “was very wild and I think did very little harm,” but it drove the Southerners back to their horses where they “mounted & escaped.” Eugene Stocking, 1st U.S. Cavalry, stated that the Regulars held their fire until the Southerners “wer[e] within about five rods from us, we gave them a volley, and they turned and run.” Then, for good measure, “we let them have one volley in the back.” It is doubtful that the brigade commander or Pleasonton was aware of the other’s situation as the Regulars crossed Goose Creek, but with a brigade now established on the Southern flank a combined push by the three brigades against Stuart’s two might have achieved decisive results. As it was, the firing sputtered out with nothing gained. The Regulars held their position throughout “a very cold and rainy night,” without food or protection against the elements, and drove off several attempts by the Confederates to recover their dead and wounded. The following day the brigade withdrew east of Middleburg.

Related Battles

350

40