10 Facts: Middleburg

In 2012 the American Battlefield Trust worked to save 5 acres of the Mount Defiance position at the Battle of Middleburg. The Battle of Middleburg, coupled with the battles of Aldie and Upperville, were important cavalry engagements at the start of the Gettysburg Campaign.

This article was produced with the considerable help of Clark "Bud" Hall, Bob O'Neill, and Childs Burden, true experts on the Battle of Middleburg.

Fact #1: The Battle of Middleburg, one of the first battles of the Gettysburg Campaign, was fought by Federal cavalry seeking the location of the Army of Northern Virginia

By the middle of June 1863, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. Joe Hooker expressed uncertainty as to the whereabouts and strategic intentions of Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. Was Lee retrograding towards Richmond? Or, was Lee moving the Army of Northern Virginia to the Western theater as some guessed at? Of greater concern to Hooker, however, was the strong possibility that Lee’s vaunted infantry might be headed toward the Potomac, far above Hooker’s right flank, threatening Washington, itself. On June 16, Hooker met with Brig, Gen. Alfred Pleasonton and issued the following direct challenge: “The commanding general relies upon you…to give him information of where the enemy is, his force, and his movements…It is better that we should lose men than to be without knowledge of the enemy, as we now seem to be.”

Lee, who was at that very moment en route on his fateful march to Maryland and Pennsylvania, was of course keen to keep his intentions hidden for as long as possible. As such, Lee ordered his cavalry chieftain, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, to operate on the eastern front of the Blue Ridge Mountains in order to screen the army’s northward advance. The subsequent battles of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville, fought on June 17-21, 1863, were a direct consequence of opposing needs by the Federals for enemy intelligence, and alternatively, a desire by the Confederates for offensive secrecy.

Fact #2: The sudden appearance of Federal cavalry in the town of Middleburg on June 17, 1863, nearly led to the capture of J.E.B. Stuart.

On June 17, 1863, Union Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick ordered Col. Alfred Duffié to advance his 1st Rhode Island Cavalry regiment to Middleburg. After brushing back pickets of the 9th Virginia Cavalry, Duffié’s cavalrymen poured into the small hamlet. JEB Stuart had been enjoying a leisurely lunch in the town of Middleburg was warned of the approaching danger and immediately beat a hasty, humiliating retreat.

Fact #3: On the first day of the battle, the isolated 1st Rhode Island Cavalry suffered 225 casualties out of 300.

Col. Duffié and the 1st Rhode Island, which had occupied the town of Middleburg, were far in advance of other supporting Federal forces, but due to absurd orders from General Pleasonton, remained inside the town of Middleburg. By the evening of June 17, 1863, the Rhode Islanders, despite putting up a valiant defense and springing a well-executed ambush, were forced to retreat south of the town. The following morning they found themselves almost surrounded by a much larger Confederate cavalry force. Unable to breakout, Duffié ordered his men to make their way to safety anyway they could. Duffié and 31 of his men made it back to the Union lines, but of his original 300 troopers, 6 were killed, 9 wounded, and 210 missing, or captured.

In 2009, the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry’s captured battle flag, which had been in the North Carolina Museum of History’s collection, was returned to the State of Rhode Island.

Fact #4: On June 19th, J.E.B. Stuart positioned his defensive line at Mount Defiance, a prominent ridge, just west of Middleburg.

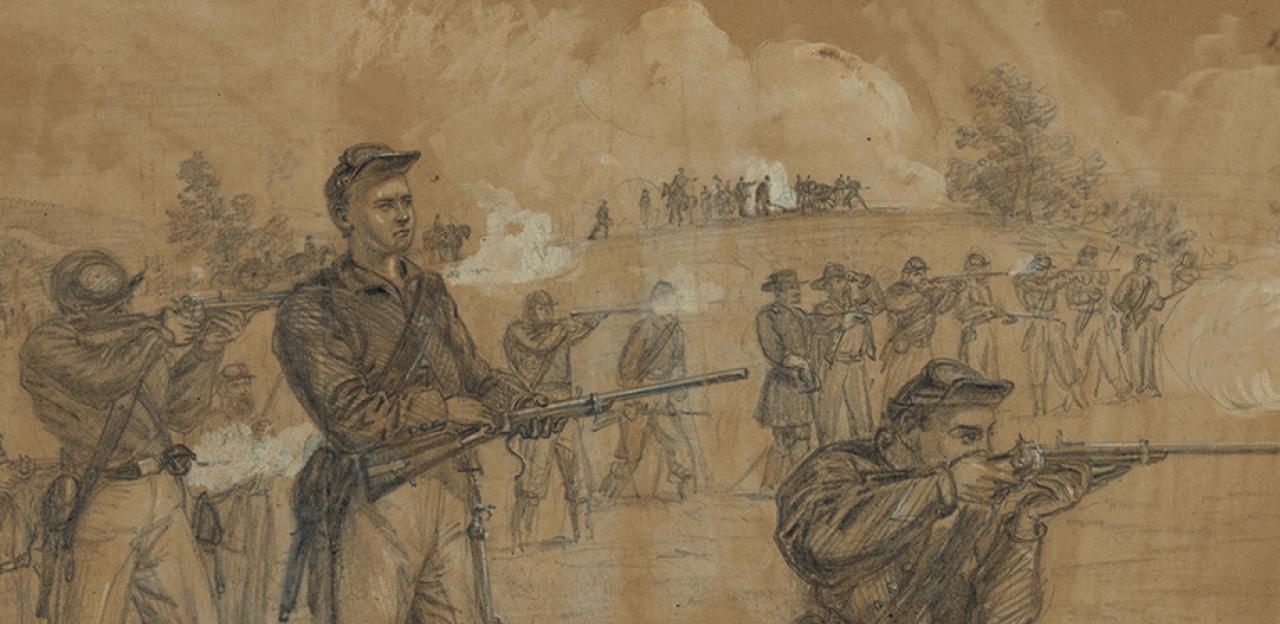

After the Battle of Aldie and the early fighting in and around the town of Middleburg, JEB Stuart ordered his cavalrymen to pull back and take position a mile west of Middleburg at Mount Defiance-- an excellent defensive platform from which to further delay the Federal advance. Not only would a successful defense here prevent unnecessary damage to the “patriotic” town of Middleburg, but Mount Defiance’s height and position along Ashby’s Gap Turnpike (modern Highway 50) rendered it a strong position to further thwart any Federal advance. What made Mount Defiance even stouter were the stone fences that bordered the road at this location. From these positions, Stuart’s horsemen could easily defend against any incursions up the road. Lastly, Stuart placed two batteries of horse artillery along the ridge, with one artillery piece pointed right down the Ashby Gap Turnpike towards the western edge of Middleburg.

Fact #5: Much of the fighting for Mount Defiance devolved into an “Indian Fight.”

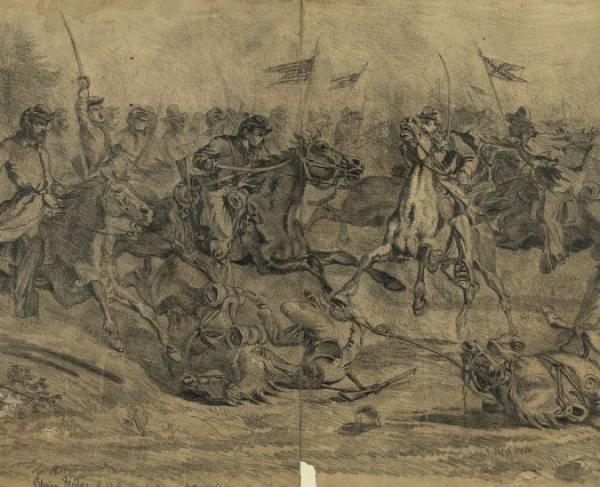

Union Col. John Irvin Gregg, cousin of division commander Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg, was ordered to attack the Confederate position on Mount Defiance on June 19, 1863. Supported by cavalry units from Kilpatrick’s division, Gregg’s troopers moved forward up the road and far out on both flanks, north and south. Southerners on the far southern end of the line deployed in a small family cemetery and were soon attacked there as Blue and Gray troopers grappled to the death among ancient tombstones. Other combatants further north on the ridge clashed violently as horses and men slammed together in a saber-to-saber fight. Union Captain Isaac Ressler of the 16th Pennsylvania declared that the fighting at Mount Defiance was “more of an Indian warfare than anything seen of late.”

Fact #6: Maj. Heros von Borcke, the Prussian chief of staff to J.E.B. Stuart, was grievously wounded at Middleburg.

After the 9th Virginia counterattacked and drove back the 1st Maine from Mount Defiance, Confederate attention was focused on the faltering southern flank of Stuart’s line. Stuart and several of his staff officers, including the huge Maj. Heros von Borcke, galloped down into the retreating North Carolinians in order to rally those troopers. Emerging from a line of trees, this group of officers was taken under fire and von Borcke was shot in the throat. After being pulled from the field with great difficulty, Jeb Stuart believed that von Borcke was dead, or soon would be. Despite this terrible wound, von Borcke survived and later returned to his native Prussia. Middleburg would be von Borcke’s last American Civil War battle.

Fact #7: The arrival of Federal cavalry forces on both of Stuart’s flanks forced him to abandon his strong position at Mount Defiance.

The counterattack of the 9th Virginia on June 19, 1863 had recaptured Stuart’s position atop Mount Defiance after being briefly taken by troopers of the 1st Maine and 10th New York. Despite regaining this strong position, Stuart was forced to abandon Mount Defiance after being notified of the arrival of a small force of 1st Maine Cavalry against his right flank and the impending arrival of John Buford’s Reserve Brigade upon his left. Buford’s Regulars, having crossed Goose Creek at Millville, arrived in time to strike Stuart’s new line, nearer the town of Upperville, before darkness brought an end to the day’s fighting. Stuart held this new line until the next battle in this series of cavalry clashes.

Fact #8: The battles of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville comprise some of the largest, most vital cavalry actions of the Civil War.

When considered together, the battles of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville represent some of the largest and costliest cavalry actions of the Civil War. According to historian Robert O’Neil, these three vicious battles cost Stuart roughly 600 casualties and Pleasonton around 900. By comparison this 1,500 casualty figure equates to roughly the same amount of losses suffered at Brandy Station (1,403 combined casualties), which is considered the largest cavalry battle of the war.

Fact #9: The Union cavalry failed in its mission to detect the location and movement of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Lincoln, Stanton, and Hooker were all desperate for accurate information on the location and intention of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Fears of another Northern invasion by Lee were high. On June 16, Hooker met with Pleasonton and hotly ordered his cavalry commander “to give him information of where the enemy is, his force, and his movements...”

But despite the aggressive fighting spirit exhibited by his courageous troopers, Pleasonton utterly failed to meet this objective. It is an absolute fact that Pleasonton never provided to his commanders, as ordered, any direct, verifiable intelligence on Lee’s movements during prior to June 21, 1863.

Ironically, three of Pleasonton’s officers, transporting highly sensitive documents, were captured by John Singleton Mosby near Aldie on June 17, 1863. These captured plans gave Stuart and Lee revealing information about the current movements of the Army of the Potomac.

Fact #10: Despite his success in fulfilling Lee’s orders, J.E.B. Stuart was criticized in the Southern press for his “retreats” at Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville.

Robert E. Lee ordered J.E.B. Stuart to operate east of the Blue Ridge Mountains and shield his army’s movement north to the Potomac. Stuart’s horsemen, pressed by aggressive and increasingly confident Federal cavalry, managed to succeed in fulfilling these important orders. Stuart’s cavalry force interdicted these bold Union forays, and in several cases delivered painful blows to their foe. Stuart also wisely traded ground for time, while ordering several well-timed retreats that preserved his stout blocking force. Despite these superb battlefield achievements, many Confederate officers and the Southern press took Stuart to task. Already critical of Stuart’s embarrassing surprise at Brandy Station, the fact that Stuart repeatedly retreated in the face of his Union foe appeared to suggest further deterioration of the Confederate cavalry arm. The Savannah Republican in fact reported on June 25, 1863 that “[the cavalry engagements culminating at Upperville] are considered quite discreditable to the Confederate cavalry, or rather to General Stuart….” And the Richmond Whig reported on October 2, 1863 that “Nobody expects our cavalry now to do anything but fall back…” and the action in Loudoun County in June 1863 was “the most famous cavalry ‘fall back’ of the war, that from Middleburg to Ashby’s Gap.”

Learn More: Gettysburg Campaign

Related Battles

350

40