The Battle of Mill Springs

Both the Union and the Confederacy thought the neutral state of Kentucky would be valuable to their side. The state's Cumberland Gap provided access into Western Tennessee, and it also was the third most populous among the slave states (counting whites only). Additionally, the state was a major producer of wheat and livestock, supplies sorely needed by the armies. The control of Kentucky by the Rebels would have made the Ohio River the Northern boundary of the Confederacy and would have devastated Union morale. For the Union, Kentucky served as a buffer for the important states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Northern leaders hoped it would be the future jumping-off point for an invasion of the Confederacy in the West. It is no wonder then that President Lincoln remarked that, while he hoped to have God on his side, he had to have Kentucky.

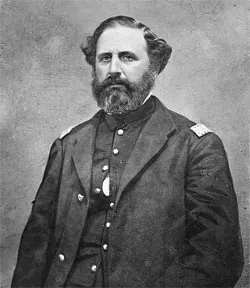

Confederate General Felix K. Zollicoffer had guarded the Cumberland Gap against Union attempts to get into Tennessee since the Fall of 1861. As part of his strategy he had sent about 4,000 men across the Cumberland River where they established a fortified camp near the town of Mill Springs.

In mid-January 1862, General George B. Crittenden arrived to assume command of Zollicoffer's forces. The Rebel camp near Mill Springs was in a vulnerable position because retreat back across the river's strong currents would be extremely difficult and likely to result in disaster. Fearing the imminent arrival of Union General George B. Thomas' army, Crittenden decided to launch a preemptive assault against Thomas' forces.

On January 17, Thomas reached Logan's Cross Roads, a small hamlet consisting of only a few rough houses and a post office, ten miles north of Zollicoffer's camp. Crittenden knew he had to attack Thomas' forces before they had a chance to concentrate: A Union victory might very well mean the loss of support for the Confederacy in eastern Kentucky in addition to the eventual loss of part of Tennessee. At midnight on January 18, Crittenden ordered General Zollicoffer and another general, William H. Carroll, to attack the Union forces at Logan's Cross Roads.

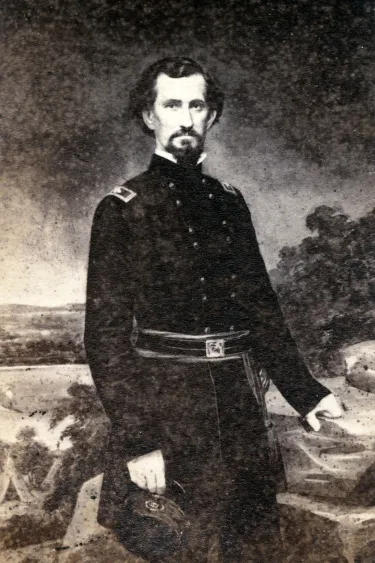

The determined Rebels endured a nine-mile march sloshing through mud and driving rains. Just as the sun came up the exhausted Confederates were confronted by the Union pickets of Colonel Frank Wolford. Wolford ordered his men to fire on the Rebels and then fell back to make a defensive stand next to the 10th Indiana under Colonel Mahlon D. Manson. Colonel Manson frantically dashed through the camp of the 4th Kentucky to warn Colonel Speed S. Fry of the impending attack--to the shock and horror of the groggy Kentuckians who were just getting out of bed.

The fiery and courageous Colonel Fry led his men towards the battle. He soon viewed the Confederates advancing toward him across an open field bordered on every side by woodlands. Fry joined the battle to aid the 10th Indiana who were in a desperate fight and on the verge of defeat. A ravine running parallel to and immediately in front of the Northern positions in the open field was the source of the Union agonies. Zollicoffer had deployed his troops in the ravine before Fry's arrival. From their advantageous position the Southerners subjected Fry's men to the same murderous close-range barrage of fire that had savaged the 10th Indiana. An enraged Fry shouted to the Rebels, daring them to abandon the ravine and stand up on their feet and fight like men.

After a lull in the battle, Fry rode a short distance to the right to get a better view of the Confederate movements. Through the haze of the smoke-shrouded morning, Fry spotted a solitary figure riding toward him from the trees. Fry didn't realize it yet, but it was Confederate General Felix K. Zollicoffer! The near-sighted Zollicoffer (further hampered by the wet and smoky conditions) approached Fry, thinking he was a fellow Rebel, and warned him that his men had been firing on Southerners. Fry fled away when he saw another Rebel approaching to warn Zollicoffer that he was conferring with enemy troops! As he fled, he turned and fired his pistol. Zollicoffer fell lifeless to the ground. Soon after Fry realized to his elation that he had accomplished the rare feat of killing an enemy general. The spot where Zollicoffer was killed is today marked by the "Zollie Tree."

Despite this exhilarating triumph, Fry was forced to again confront the reality of his difficult situation. His men were being pressed from the front as well as in danger of being outflanked on their right. Fry moved two of his companies from the unmolested left flank to assist on the right. At the same time General Thomas appeared on the field and immediately placed the 10th Indiana in a position to also protect Fry's right flank. The tide began slowly to turn in the Yankees' favor due to the confusion resulting from the death of Zollicoffer and the reinforcement of Fry's troops. To compensate, Confederate General Crittenden ordered Carroll's brigade to join the forces that had been under Zollicoffer's command and advance on the reinvigorated Northerners.

The tempo of the battle again rose as the Confederate forces attacked with great courage. Things were evened up as the weather-reduced visibility that had sealed the fate of Zollicoffer now hampered the Union: muddy roads and limited visibility had rendered Thomas's huge superiority in artillery meaningless. Eventually the Union forces were able to counterattack against Carroll. The turning point occurred when the 2nd Minnesota attacked from the left while the 9th Ohio attacked from the right, and then suddenly changed direction and made a bayonet charge against the Rebels' left. Panic reigned as the Confederates retreated pell-mell leaving behind even their food provisions in the rush. Additionally, the Union forces captured ammunition, artillery, tools and muskets when they entered the camp from which the Confederates had beaten a hasty exit.

A disgusted Confederate General Crittenden acknowledged the completeness of the Union victory when he wrote: "From Mill Springs and on the first steps of my march officers and men, frightened by false rumors of the movement of the enemy, shamefully deserted, and, stealing horses and mules to ride, fled to Knoxville, Nashville, and other places in Tennessee."

A wounded Rebel prisoner, being teased by Union troops about the panicky retreat of his compatriots, replied to his accusers: "Well, we were doing pretty good fighting till old man Thomas rose up in his stirrups, and we heard him holler out: 'Attention, Creation! By kingdoms right wheel!' and then we knew you had us, and it was no time to carry weight."

Despite his great victory, lack of supplies and harsh winter weather prevented Thomas from advancing into Tennessee through the hole that he had labored so hard to create in the Rebel defensive line. However, the ramifications of Thomas' victory would become clearer in the Spring of 1862, when the Union army was again able to advance. The defense of Rebel-controlled Tennessee would cause the Confederates to divert precious resources in an effort to prevent the Federals from taking any further advantage of the crippling blow that Thomas had delivered to the Southern forces at Mill Springs.