The Battle of Stony Point

The Battle of Stony Point was one of the more dramatic battles in the Revolutionary War. Much of the combat was brutal hand to hand fighting at the point of the bayonet. While the battle itself played a minor role in the outcome of the war, it displayed to the world the prowess and bravery of American troops and served as a much-needed morale boost for the young American army.

Following the winter at Valley Forge and the inconclusive Battle of Monmouth in June of 1778, the British Army retreated to New York City, which served as their primary headquarters and base of operations. General George Washington’s Continental Army set up winter quarters just outside of New York City in Middlebrook, New Jersey. The war ground to a slow stalemate in this theater as small skirmishes occurred but no large engagements. The British began to turn their sights on the Southern colonies and in the winter of 1778-1779 dispatched troops to capture Savannah, Georgia, and begin operations in the Carolinas.

As the stalemate around New York dragged on into the summer of 1779, British General Sir Henry Clinton looked for a way to draw Washington’s main army out into the open where he could destroy it. Having captured the American cities of New York, Philadelphia, and Savannah, it was clear that the best way to bring a speedy conclusion to the war would require destroying Washington’s army. In May of 1779, Clinton sailed with a force of 6,000 British troops 40 miles up the Hudson River to capture the major crossing at King’s Ferry. This important crossing point on the Hudson River was protected by small American forts at Verplanck’s Point on the east side of the river and Stony Point on the west. The small American garrisons there quickly abandoned the forts and the large British force easily captured the area.

Washington didn’t take the bait. Instead, his army positioned itself safely nearby in New Windsor, New York, and waited to see if Clinton would make an attempt on the nearby American defenses at West Point.

After not successfully enticing Washington, Clinton decided to sail the majority of his force back down the Hudson and dispatched them to the coast of Connecticut where they raided the American shoreline. Clinton left behind at Stony Point a small contingent of 600 soldiers primarily from the 17th Regiment of Foot.

With the outpost at Stony Point isolated and vulnerable, Washington wanted to take it back. He tasked this mission to the fiery American General Anthony Wayne of Pennsylvania. Two years earlier in September of 1777 Wayne’s men had been surprised by a British night attack that resulted in more than 200 American soldiers being killed or wounded by British bayonets. Wayne survived but wanted revenge and this would be his opportunity.

Washington gave Wayne orders to take Stony Point in a midnight bayonet charge. Wayne would command a force of about 1,200 Light Infantrymen. The Light Infantry were hand-picked men from various Continental regiments that formed an elite corps of some of the best American soldiers.

Washington gave Wayne instructions to send the Light Infantry in through three different points “with fixed Bayonets and Muskets unloaded.”

Stony Point is a tall rocky outcropping that juts into the Hudson River. Rising up to almost 150 feet above the water, the ground the Americans needed to cover was extremely steep. A narrow neck of land connected the point to the mainland. On either side of this neck was tidal marshland. The British had fortified the already naturally defended position. They had a couple lines of earthworks and placed abatis (obstacles made by placing tangled and sharpened branches) in front of the earthworks.

On the afternoon of July 15, 1779, Wayne’s force moved into position just a mile from Stony Point. The time for the assault would be at midnight. There would be three columns to make the assault. The main column, led by Wayne personally, would attack across the southern part of the marshland and scramble up the point. A second column would advance across the northern marsh and a third column, meant to be a diversion, would attack directly across the neck and fire as much as possible to distract the British defenders. Secrecy would be extremely important as they wanted to be on top of the British works as quickly as possible and capture them by surprise. For this, all the men were ordered to not load their muskets. They would go into battle with empty muskets and fixed bayonets. Wayne directed them to “place their whole dependence on the Bayonet.”

An hour before the assault, Wayne wrote a letter to a friend stating, “This will not reach you until the writer is no more.” After asking his friend to look after his children, he wrote that he would be eating breakfast “either within the enemies’ lines in triumph, or in another world.” Wayne was determined to capture the post or die trying.

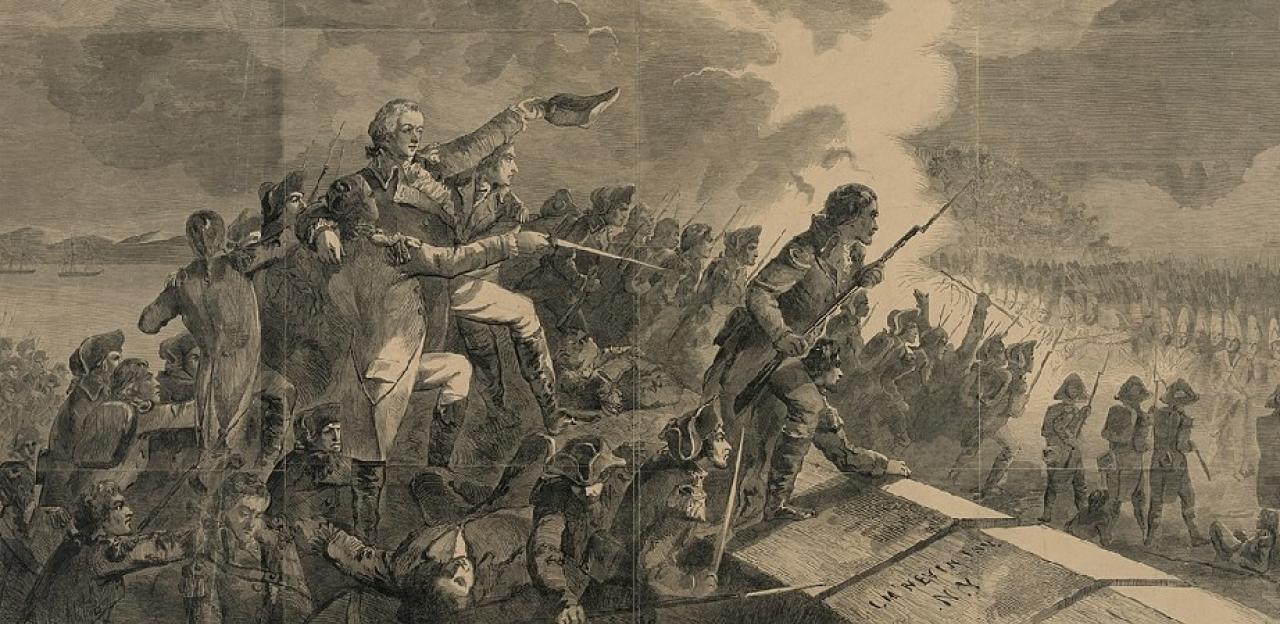

Shortly after midnight on July 16, 1779, the three columns moved out. As Wayne’s column began to cross the marsh, they slugged through water that came up to their chests. The men pushed forward into the darkness. As soon as they came to the other side, they began to dash up the steep slopes towards the first line of British defenses. British sentries, seeing the movement in the darkness began to fire into the mass of men surging towards them. Bright musket flashes illuminated the dark night as whizzing musket balls screeched through the air.

As American soldiers began to fall, the disciplined men closed their ranks and continued to push forward. In the vanguard of the assaulting troops were Americans armed with axes in order to hack away at the abatis and obstacles to allow the main body to push through. Just as the north and south columns engaged the British sentries, the center column advanced to the neck and began firing at the British.

As he advanced boldly, a British musket ball hit Wayne in the head. He fell to the ground wounded. The ball had luckily only grazed his head, and though bloodied and dazed, he cried “March on, boys. Carry me into the fort! For should the wound be mortal, I will die at the head of the column.”

Lt. Col. Henry Johnson, the British commander, fell to the American ruse by rushing many of his men down to neck where the third American column was creating a diversion. Johnson soon realized his predicament when he heard the other American columns in his rear.

The American columns made it into the inner works and for a few minutes, the rocky peninsula was a maelstrom of musket shots and bayonet thrusts. Lt. Colonel Francois de Fleury was the first man into the inner works and pulled down the British flag flying there and exclaimed, “The fort’s our own!” After more bloody hand to hand combat, it was clear that further resistance by the British was futile, and Johnson and the British troops surrendered. A few minutes later a victorious and bloody Wayne was carried into the British works and cheers went up among the American troops. Wayne quickly jotted a letter to Washington: “The fort and garrison with Col. Johnston are ours. Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free.”

The battle resulted in 15 Americans killed and 83 wounded. The British had lost 20 killed, 74 wounded and 472 captured. This action displayed the fierceness of the American troops and exacted revenge for the massacre at Paoli. Wayne displayed great courage in the battle and would later be given the name “Mad” Anthony Wayne for his zeal in battle. Wayne and the American troops also displayed great restraint, in preventing a retaliatory massacre from occurring, and instead gave mercy and quarter to the surrendered British soldiers.

Washington visited the conquered position on July 17, 1779. He determined his army could not hold the isolated position at Stony Point with the possibility of the British Navy returning and ordered the fortifications destroyed and left with the provisions and prisoners. The British reclaimed the place on July 19.

The success and bravery of the Light Infantry was not lost on Washington. Two years later he would employ near-identical tactics to launch an evening bayonet charge on British redoubts outside of Yorktown, Virginia, in what would be the last major battle of the Revolutionary War.

Further Reading

- Forts of the American Revolution By: René Chartrand

- Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown 1781 By: Jerome Greene

- “The British Engineers in America 1755-1783.” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. Vol. 51, No. 207, pp. 155-163. By: Douglas Marshall

-

Unlikely General: "Mad" Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America By: Mary Stockwell

- Engineers of Independence By: Paul Walker