Utoy Creek

Atlanta, GA | Aug 5 - 7, 1864

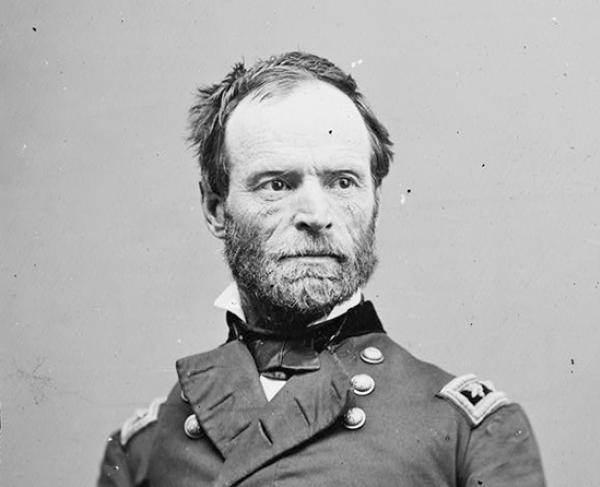

In the days following Ezra Church, Gen. William T. Sherman ordered Generals George Thomas and John Schofield to keep testing and pressuring the Rebels in their front. With his artillery bombarding Atlanta, Sherman pursued his plan of inching his army's right flank southward toward the Macon & Western Railroad between Atlanta and East Point. His hope was "to draw the enemy out of Atlanta by threatening the railroad below." Sherman was confident that by thinning and extending his lines, shifting Thomas' and Gen. Oliver O. Howard's armies ever to the right, he could reach East Point and cut the Rebels' supply artery. On July 31, Thomas reported that Howard had very nearly reached the railroad. To complete the movement, Sherman decided that Schofield's Twenty-Third Corps, then east of the city, should swing around the army and take up position on Howard's right. He therefore ordered Schofield to march around to the west and south. On August 2, the Army of the Ohio moved to its new position, a mile or more south of Ezra Church, across North Utoy Creek. A mere two miles farther lay the common line of the Macon & Western and Atlanta & West Point Railroad, the Federals' tantalizing objective.

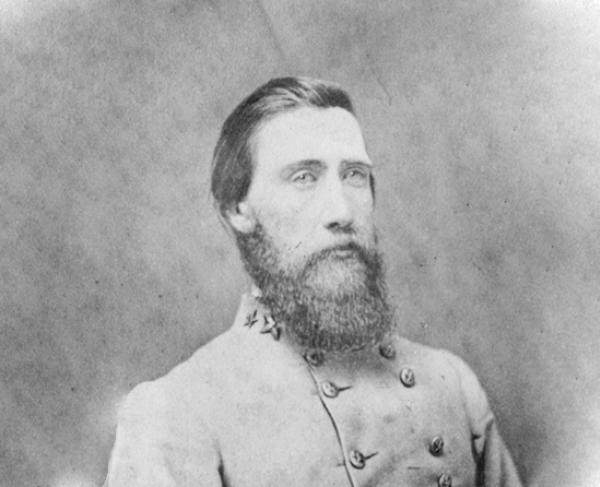

Gen. John B. Hood knew the enemy's goal, as cavalry fed reports of the Yankees' movements. Already guarding the railroad were S.D. Lee's troops, aligned southwestward from a salient in Atlanta's western works. On July 31, Hood ordered Bate's division of Gen. William Hardee's corps to reinforce Lee's left flank, extending it more than four miles from the Confederates' main perimeter to the South Fork of Utoy Creek. During the next several days, the Southerners constructed a "railway defense line" southwest of Atlanta, with rifle pits and artillery forts running eventually a mile or more below East Point.

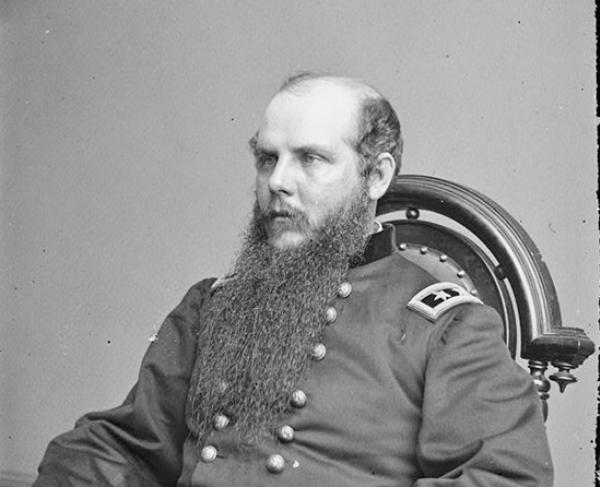

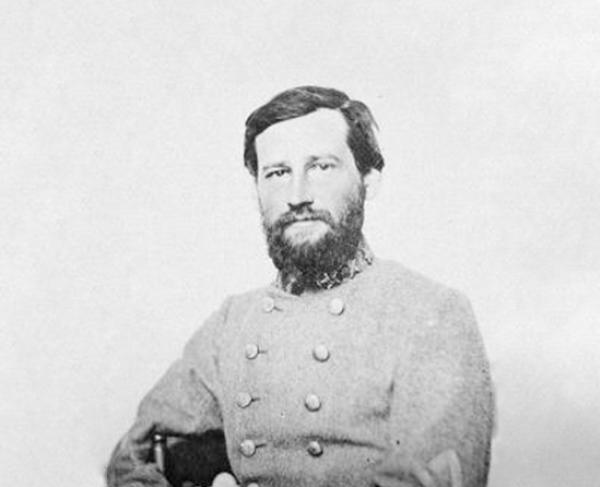

On August 4, Sherman decided it was time to move forward and seize the railroad to East Point. He ordered Schofield to advance his Twenty-Third Corps plus Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer's Fourteenth Corps (of Thomas' army) and "not stop until he has absolute control of that railroad." The next day only one Union brigade, Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird's, moved forward and seized an entrenched skirmish line with 140 prisoners, at the cost of 83 killed and wounded. But such was the complete gain for the whole day, a trifle for which Schofield felt compelled to apologize. For the next morning, Schofield ordered part of his corps to attack at Utoy Creek. By the time the Federals advanced, Bate's division had taken position on a ridge west of the main defensive line, south of Sandtown Road. The Confederates were ready. The Rebels had strengthened their works with abates; Union soldiers had heard the felling of trees. Into this entanglement and up the slope the troops of Col. James W. Reilly's brigade charged around 10 a.m. and Bate's division opened with heavy musketry and cannon fire, driving them back. Another Union advance also met with repulse. Altogether Reilly lost 76 killed, 199 wounded and 31 captured, against 15-20 casualties in Bate's command.

Schofield, mindful of Sherman's insistence on finding a way to the railroad, sent a division farther west to flank Bate's line. Late in the afternoon, two Federal brigades charged a battery guarding the Rebels' extreme left and pushed it back at the cost of several hundred casualties. The bluecoats failed to make more headway before nightfall, but the flanking move eventually forced Bate to withdraw his division to the main Confederate line. The next day, August 7, Schofield sent his infantry forward to probe the enemy position, and found the Southerners "strongly fortified and protected by abatis," too strong for his corps to tackle alone. Even the Fourteenth Corps, now under Brig. Gen. Richard Johnson (Palmer had resigned over rank) finally got into action, incurring nearly 200 casualties in sallies against the Rebel works. Sherman termed the whole day's proceeding "a noisy but not a bloody battle."

From the fighting at Utoy Creek, August 5-7, Sherman pondered two points. First (as if he did not already know it), infantry assaults against obstacles and trenches were futile. He had lost close to a thousand men over the several days, while Confederate casualties, in the hundreds, arose mainly from skirmishers captured in their rifle pits. Sherman's second lesson was that Hood had constructed a trench line far enough to guard the railroad from Atlanta to East Point. Sherman's grand wheel to the right, begun July 27 with Howard and followed by Schofield, had been blunted. Seemingly out of flanking options, Sherman’s armies settled in and besieged Atlanta.