The Battle of Wilson's Creek and the Struggle for Missouri

WILLIAM BARRETT PISTON; HALLOWED GROUND MAGAZINE

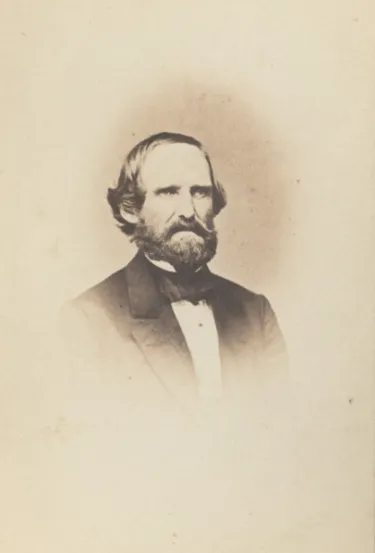

By all accounts the heat on August 10, 1861, was sweltering, even by early morning, but the temperature was not the only reason Ben McCulloch’s black velvet civilian suit was inappropriate. Although he was a brigadier general in the Confederate army, the former Texas Ranger disdained uniforms and there was little other than his determined manner to indicate that he commanded the largest Confederate force west of the Mississippi River. Now he led the Western Army in desperate battle among the oak-covered hills and creek bottoms of southwestern Missouri. “That was a good shot,” McCulloch said to Henry H. Gentiles, a corporal in the 3rd Louisiana Infantry. Gentiles had killed the lone Union sentry guarding the Federal position at the Sharp farm just as the man was about to shoot McCulloch. Calling on his soldiers to “give them hell,” McCulloch ordered a charge, leading his army from the very front. On another part of the field, his opponent, Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon, also led from the front, wearing a worn captain’s coat rather than the finery entitled by his rank. About an hour after McCulloch led his charge, a bullet struck Lyon’s heart while he was maneuvering troops into position, making him the first Union general to die in battle. Lyon’s death and McCulloch’s almost foolhardy courage are but two of the many circumstances that make the Battle of Wilson’s Creek memorable. Fought just twenty days after the Union debacle at Manassas in Virginia, Wilson’s Creek was the second major Confederate victory of the war. It played a key role in the struggle for Missouri and the Trans-Mississippi Theater. Many Confederates called the battle Oak Hills, and oak trees and prairie grass still dot the 1,929 nearly pristine acres that make the Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield one of the jewels of the National Park Service.

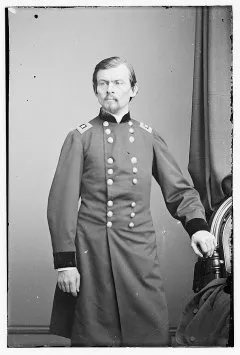

The circumstances that produced the clash at Wilson’s Creek were unusual, even amid a great civil war. Although a convention meeting in March 1861 had rejected secession, Missouri governor Claiborne Fox Jackson favored the Confederacy. In May he used the state’s militia to threaten the Federal arsenal in St. Louis. This critical post was commanded by Nathaniel Lyon, who employed a small force of Regulars and a large number of volunteers to capture the state militia encampment on the outskirts of the city. Although the militia surrendered without a fight, a riot ensued as Lyon marched his prisoners through the city. Over 100 civilians became casualties when Lyon’s men fired into the crowd. This “massacre” panicked the largely pro-Union legislature into giving Governor Jackson nearly dictatorial powers to defend the state. Jackson named former governor and Mexican War hero Sterling Price a major general to command a re-organized militia, now styled the Missouri State Guard. Its ranks swelled with volunteers, many (but not all) of whom hoped to see Missouri join the Confederacy.

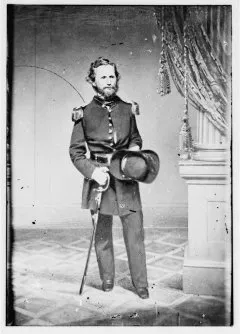

Lyon did not give the potentially hostile State Guard time to organize. In June he declared war on the Missouri state government (an unauthorized action retroactively sanctioned by the Lincoln administration). Receiving reinforcements from Kansas, he launched three columns into motion, forcing the state legislature from the capital at Jefferson City, breaking up recruiting camps, and driving the State Guard units that had formed into the southwestern corner of the state. Skirmishes occurred, notably at Boonville on June 17 and Carthage on July 5, and by the first of August Lyon had a force of some 7,000 men concentrated at Springfield. His bold actions had secured the critical river and railway networks in the central portion of the state for the Union, but he also faced great peril. Lyon’s Army of the West had penetrated deep into the Ozarks, far from the nearest railhead, at Rolla, forcing his men to go on short rations. Many of the volunteers had enlisted for only ninety days; within weeks half of Lyon’s force would cease to exist. The new top commander in Missouri, Major General John C. Frémont, refused reinforcements and urged Lyon to retreat to Rolla.

Retreat would not be easy, for Lyon now faced a formidable foe, camped just nine miles from Springfield, where the Telegraph or Wire Road crossed Wilson Creek. When Lyon’s lightning campaign forced the Missouri State Guard to retreat southward, Sterling Price sought help from Ben McCulloch, commander of the Confederate forces in northwestern Arkansas. In July McCulloch secured permission from Richmond to make a forward defense by cooperating with Price. The Texan moved 5,000 men into Missouri, the first Confederate invasion of the Union. Joining the State Guard near Cassville, they advanced toward Springfield. After several skirmishes with Lyon’s advance forces, they settled into camp on August 6 at Wilson Creek, where local springs and farms provided food and water. Both McCulloch and Lyon sent out patrols and used spies (who included local women) to collect information as they planned their next moves.

The opposing forces were unusual in many ways. McCulloch commanded the Western Army by consent. His Confederate brigade consisted of Confederate troops under his direct command and Arkansas State Troops led by Brigadier General N. Bart Pearce. The latter were Arkansas militia temporarily placed at McCulloch’s disposal. In addition to Arkansans, the Confederate brigade included units from Louisiana and Texas. Most carried antiquated, short-range, smoothbore muskets. Many wore civilian clothes, sometimes trimmed in flashy colors for a military appearance. Others wore uniforms of blue, black, or gray, sewed by loved ones in their home communities. Price’s Missouri State Guard was 7,000 strong, but only 5,000 were armed. While a few units wore fancy blue or gray pre-war militia uniforms, and some were uniformed by their home towns, civilian attire predominated. A large number wore trimmed civilian shirts as an outer garment, a precursor of the fanciful Missouri “guerrilla shirts” of later years. While some members of the State Guard had military arms, many carried shotguns or hunting weapons brought from home and a high percentage of these were flintlocks. All of the Southerners were ragged from marching and hundreds lacked replacements for worn-out shoes. More significantly, the Western Army was critically short of ammunition, averaging only twenty-five rounds per man. As this Southern force rested in the valley of the creek, a dozen or so Cherokee arrived from the nearby Indian Territory and attached themselves casually to the army. There were a large number of civilians in the camp, mostly soldiers’ wives who had followed the army. Quite a few officers employed their slaves as cooks or body servants; perhaps one hundred African Americans were present.

Nathaniel Lyon’s force contained a larger ethnic component than any other army the Union sent into battle during the war. About two-thirds of the more than 1,000 Regulars under his command were born in Germany or Ireland. He had two regiments of volunteers from Kansas, but 45 percent of their men were born outside the United States. An infantry unit from Iowa had three German companies, while Lyon’s volunteer infantry and artillery units raised in Missouri were mostly German-born residents of St. Louis. Although Lyon’s Regulars and the Kansans dressed in blue, most of his Missouri troops wore gray overshirts, and each company in the 1st Iowa sported a different color outfit, including black, gray, and shades of blue. Like their Southern opponents, Lyon’s men were bedraggled from marching and many had replaced all or part of their uniforms with civilian clothing. A considerable number no longer had shoes, but ammunition was not a problem. While it does not appear that any wives accompanied Lyon’s army, some of his officers were slaveholders who brought personal servants. Lyon was an ardent abolitionist, but some of Missouri’s leading Unionists held slaves.

Ironically, both Lyon and McCulloch committed their forces to attack at the same time. Pressured by Price to take action, McCulloch decided to advance on the night of August 9 and assault Springfield at dawn. When a storm threatened, he ordered a delay until the next morning, as many of his soldiers lacked cartridge boxes for their precious ammunition. The storm never developed; after a slight sprinkle the Southern army slept peacefully, but McCulloch neglected to repost sentries to guard the camp. That same day, in Springfield, Lyon and his officers debated their next move. With supplies critically short the Federals had to retreat eventually, but Lyon feared McCulloch would overtake him and force him to fight at a disadvantage. Lyon was also loath to withdraw without striking a blow for the Union cause. He therefore decided to attack the Southern camp at dawn, hoping to damage the enemy sufficiently to allow the Federals to escape safely to Rolla. But Colonel Franz Sigel convinced Lyon to adopt a more daring plan. The German-born veteran of European conflicts argued for a two-pronged attack on the enemy camp. Lyon agreed, for reasons that have never been clear. To divide the numerically inferior Federal force was a breathtaking risk, but an attack from two directions might multiply the Federals’ main advantage – surprise. Some officers believed that Sigel made the argument just to win a prominent role, for Lyon assigned one of the two columns to him.

The Federals left Springfield in the evening. Lyon’s column, with 4,300 men and ten guns, followed roads leading west before turning south and marching cross-country. They halted just north of their unsuspecting enemy and then rested. Sigel had further to go. His column of 1,100 men and six guns marched almost all night, but reached a position on high ground overlooking the southern end of McCulloch’s camp just before dawn. The plan was for Sigel to open fire when he heard Lyon’s guns.

It is not clear how much the Federals knew about their enemy’s position. The Southern army had fifteen guns in four batteries. One of these, the Pulaski Light Battery, sat at the Winn farm, on high ground overlooking the Wire Road, protecting the Southerners from any attack coming down the road from Springfield. Beyond that the Southerners were camped almost at random. Most of McCulloch’s own Confederate units were positioned on a plateau on the east side of Wilson Creek, not far from where the Wire Road forded the stream. The bulk of Pearce’s Arkansas State Troops were on the same plateau, just to the south. The Missouri State Guard was scattered. Price’s men were organized into five unequal, mixed units labeled “divisions,” each commanded by a brigadier general. The infantry and artillery from four of these was camped at the William Edwards farm, flat ground on the west bank of Wilson Creek, just south of the ford. The accompanying cavalry (together with some Confederate units) were further south and almost out of touch. They camped at the Joseph Sharp farm, on a high plateau above the valley of the creek. Brigadier Generals John B. Clark, William Y. Slack, Mosby Monroe Parsons, and James H. McBride commanded the divisions at the Edwards farm. The remaining State Guard division, under James S. Rains, was scattered. The infantry and one battery were at the Caleb Manley farm, on a hill east of the creek and some distance from the main camp. The cavalry was camped on and about a broad undulating hill on the west side of the creek, just north of the Edwards farm. Unnamed at the time, it soon earned the sobriquet “Bloody Hill.” Rains’s headquarters was upstream from the rest of the camp, at the gristmill of John Gibson, which sat on the east bank of the creek, opposite a ravine leading up Bloody Hill.

Just before dawn, Lyon’s column entered the Elias B. Short farm, adjacent to a northern spur of Bloody Hill. Southern foragers had noticed his approach and raised the alarm. Lyon was surprised to find a small cavalry unit on the spur ridge, disputing his passage. The Federal commander took about an hour to deploy his artillery, charge the ridge with his infantry, and drive them away. Reaching the ridge top, Lyon could see the main body of Bloody Hill to his front, across a steep ravine. Rains’s headquarters was across Wilson Creek on his left, but the main Southern camp was out of sight, on the far side of Bloody Hill, three-quarters of a mile away. Because the ravine was steep, Lyon sent only two infantry units and one battery straight forward. The bulk of his force moved to the right, along a farm road that took them west, curving around the head of the ravine, to outflank the resistance Lyon could see forming on Bloody Hill. To guard his left flank Lyon dispatched Captain Joseph Plummer with 300 Regulars and some mounted Home Guard cavalry to cross the creek and secure the Wire Road.

When Sigel heard Lyon’s guns at daybreak he ordered his own artillery to open fire. The surprise was complete and the effect devastating. Artillery shells rained from the Federals’ hilltop position onto the unsuspecting Southern cavalrymen cooking their breakfast at the Sharp farm. In moments the 1,500 men camped there were in flight; more than half of them left the battlefield altogether. After a short time Sigel led the bulk of his force off the high ground and moved toward the Sharp farm. He and Lyon had successfully maneuvered in secret and caught their foe by surprise, a stunning achievement.

The Federals’ success was even greater than they knew. Down in the valley of Wilson Creek, McCulloch and Price shared breakfast at Price’s headquarters, a tent pitched next to the Edwards cabin. As dawn gave way to full light a bizarre acoustic shadow prevented them from hearing the Federal artillery firing both north and south of their position. Thirty minutes or more may have elapsed before messengers brought word that Federal soldiers were storming up Bloody Hill. Shortly thereafter, McCulloch also learned of Plummer’s movement and Sigel’s success. The Texan responded by ordering Price to lead the Missouri State Guard up the slopes of Bloody Hill while he dealt with the other threats.

The Federals appeared to be unstoppable. Lyon’s 1st Kansas and 1st Missouri, supported by Captain James Totten’s battery (Company F, 2nd U.S. Artillery), crossed the ravine and easily drove from the crest of Bloody Hill the small units Rains had positioned there. The fleeing State Guardsmen took refuge with their compatriots at the base of the hill, where Price was struggling to organize a line of battle. While Lyon waited for the remainder of his column to arrive, Totten deployed his battery and began firing southeast, across the creek. His target was the Pulaski Light Battery, which guarded the Wire Road at the hilltop Winn farm. The Arkansas militiamen turned their guns toward the threat and returned fire. This noisy duel attracted Plummer’s attention. He had crossed Wilson Creek near Gibson’s mill, entering a large cornfield belonging to John Ray, whose farm house sat next to the Wire Road. Plummer decided to attack the Pulaski Battery; his men marched through the shoulder-high cornstalks with confidence.

Meanwhile, to the south, Sigel brought his remaining forces off the high ground and continued his advance, following a small road toward the Sharp farm. When he noticed some of the Southern cavalry rallying near the Sharp farm house and along the creek, he formed a line of battle in the stubblefields where the Southerners had been camped. Before the Southern horsemen could charge, Sigel’s artillery drove them into flight a second time. The Federals continued their advance, reaching the Wire Road. They were in the rear of McCulloch’s army, squarely across his line of communications. It was about 8 a.m.

But as the sun rose to its full force, the initiative began to pass to the Southerners. McCulloch placed a unit to support the Pulaski Battery and dispatched Colonel James McIntosh to deal with Plummer. McIntosh led the 3rd Louisiana and the dismounted 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles up the Wire Road to the Ray farm, where they collided with Plummer at the edge of Ray’s cornfield. McIntosh outnumbered Plummer more than two-to-one, but the standing corn hid the Federals’ weakness. After thirty minutes of indecisive firing, McIntosh led a charge that drove the Federals back to the Gibson mill and across the stream. This advance threatened Lyon’s left flank and rear. But as Lyon’s forces came around the head of the ravine and began deploying atop Bloody Hill, quick action by a battery commanded by Lieutenant John V. Du Bois saved the day. Firing across the creek, Du Bois shelled the Southerners, causing them to retreat in a panic. Fighting on this portion of the field ceased, leaving neither side with an advantage.

Meanwhile, as his battle line lengthened on the crest of Bloody Hill, Lyon sent the 1st Missouri and 1st Kansas cautiously forward, probing downhill among the waist-high prairie grass. Within a few minutes the Federals ran into units of the Missouri State Guard. Price was struggling to form his own battle line near the base of the hill, with his right flank anchored on the creek. The sounds of muskets and shotguns soon filled the air. The State Guard had little training or practice with drill, so Price led units individually from their camps and placed them carefully into position. This took time, but the Missourians eventually outflanked Lyon’s two regiments, forcing them to withdraw under pressure. As the Southerners advanced, Lyon brought up reinforcements. These and his well-trained artillerists drove the Southerners back down the hill. A lull ensued. Lyon had possession of Bloody Hill, but he had lost the initiative. His attempt to attack the Southern camps had failed and thereafter he fought on the defensive. Much would depend on the actions of the column under Sigel.

Sigel reached the Wire Road about 8 a.m. Within moments his artillery was firing on Bloody Hill, striking Price’s units in their rear as they fought against Lyon. Sigel soon halted the firing, however, because he could not clearly tell friend from foe as the distant figures maneuvered back and forth in the tall prairie grass. The soldiers on both sides wore every uniform color imaginable as well as civilian clothes, and flags hung limp in the morning heat. Sigel was content to place his cavalry on his flanks and leave the bulk of his infantry in column on the road. He failed to send an adequate force of pickets into the low ground directly to his front, to guard against surprise. His main concern was to prevent “friendly fire” casualties should Lyon’s column break through and join him on the plateau at the Sharp farm, but he dispatched no messengers to inform Lyon of his presence or progress.

While these events were unfolding McCulloch remained busy. After receiving an inaccurate report that the Federals were also approaching from the east, he left most of Pearce’s Arkansas State troops on the plateau by their camps. Then, from a small rise, he witnessed Sigel’s arrival at the Sharp farm and moved immediately to end this threat to the Southern army’s rear. Calling upon a portion of the 3rd Louisiana which had rallied at the ford of Wilson Creek after their fight at the Ray farm, he led them into the low, concealed ground just in front of Sigel’s position. A few Missouri State Guard units joined him. As the Southerners advanced up hill they encountered Corporal Charles Todt of the 3rd Missouri Infantry, Sigel’s lone sentry guarding against surprise. Todt challenged the approaching force and drew a bead directly on McCulloch, but Corporal Henry Gentiles shot him down before he could fire. After McCulloch complimented Gentiles on his marksmanship, the Southerners charged. Batteries from the Missouri State Guard and Arkansas State Troops opened fire in support. When the Louisianans reached the plateau and opened fire, Sigel assumed they were Federals and ordered everyone to cease firing. By the time he realized they were the enemy it was too late. McCulloch’s surprise attack swept Sigel’s column from the field in a panic. Sigel risked his life to rally his men but the task was impossible. The disordered Federals fled back to Springfield by various routes, losing five of their six guns.

On Bloody Hill the initiative passed from Lyon to Price. About 9 a.m. the Missouri State Guard advanced slowly and cautiously. With each man having only a handful of ammunition, and many possessing short range weapons, they closed to almost point blank range before opening fire. Although outnumbered, the Federals held their own on both flanks, thanks in large part to supporting artillery, but their center nearly gave way. Lyon had already been wounded slightly in the head and right leg, and his horse was killed. Remounting, he repositioned the 1st Iowa and 2nd Kansas Infantry to meet the threat to the center. Lyon was killed while leading them into place, but his maneuvers were successful and the Southerners retreated. Price nearly suffered the same fate as Lyon. He was painfully wounded in the side as he, too, led from the front.

Command of the Army of the West passed to Major Samuel Sturgis. Under his direction the Federals survived another attack. McCulloch and Price directed this next Southern assault together. With threats elsewhere eliminated they began concentrating all their units against Bloody Hill, constantly extending their left in hope of turning the Federals’ right flank. They nearly succeeded. A lone Texas cavalry unit even made a circuitous charge into the Federal rear, only to be driven off. By about 11 a.m. the Southerners had withdrawn once again. During the lull that followed, Sturgis decided that his men had accomplished their mission of stunning the enemy. With casualties mounting and no clue as to Sigel’s fate, it was time to withdraw. Sturgis handled the tricky maneuver with great skill, leaving the field in good order even as the Southerners launched another attack. By noon the guns on Bloody Hill were silent. McCulloch made no pursuit. His men were fatigued and the Southern army’s ammunition was almost entirely exhausted.

The Federal army rallied in Springfield. Early the next morning they began a successful retreat to Rolla, leaving their contemporaries (and historians) to argue over who won the battle. The Southerners held the field, and they had routed Sigel’s column, but Lyon’s column left of its own volition and the Federals accomplished safely the strategic withdrawal they had intended to make all along. Meanwhile, more than 2,000 men lay dead or dying in the August heat. The Federals had lost a quarter of their army, the Southerners more than 12 percent, making Wilson’s Creek one of the bloodiest battles in American history up to that time.

The fight is best understood not as a clear-cut win or loss for either side, but as an important point in the long-term struggle for control of Missouri and the Trans-Mississippi. Following the battle McCulloch took his Confederates back to Arkansas. Price surged north with the Missouri State Guard, capturing a large Federal garrison at Lexington, on the Missouri River, in September. Some 20,000 new recruits rushed to join him. Price, however, had no logistical base, no facilities to feed, clothe, or equip his army in the long term. During the fall and winter, as the Federals drove him back to Springfield and then into Arkansas, two-thirds of Price’s men deserted. For the Federals, the fight at Wilson Creek and Price’s subsequent advance were annoying distractions from their main mission, which was to open the Mississippi River. They could not do so with a hostile force threatening their rear. John C. Frémont commanded the initial movement driving Price back. Later, Major General Samuel R. Curtis took command, beginning the maneuvers that would lead to the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March, 1862. That Federal victory cemented their control of the region, essentially completing Nathaniel Lyon’s work. Thereafter Federal control of Missouri was threatened by raids and disturbed by guerrillas, but never seriously challenged.

Missouri remained a bitterly divided state. In October, a rump session of the state legislature passed an ordinance of secession and a few weeks later Missouri became a Confederate state – in name, at least. In reality the Confederate government of Missouri was a government in exile. Some 40,000 Missouri Confederates fought gallantly in Arkansas, Louisiana, and the Indian Territory, as well as in states east of the Mississippi River, returning only at war’s end. More than 60,000 Missourians fought for the North, some even accompanying Major General William T. Sherman on his march to the sea. But whether they wore blue or gray, they all followed a very long road, one which had begun on a hot day in August 1861, when gunfire echoed amid the scattered oaks and tall prairie grass on a yet unnamed hill, and blood stained the water of Wilson Creek.

Author Note: Wilson Creek is the correct name for the body of water. Soldiers misunderstood it to be Wilson’s Creek, giving that name to the battle.

Professor William Garrett Piston has taught at Missouri State University since 1988. He is co-author (with Richard W. Hatcher III) of Wilson’s Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It and Kansans at Wilson’s Creek; Soldiers’ Letters from the Campaign for Southwest Missouri. In 2004 he testified before the House Subcommittee on National Parks as part of a successful effort to expand the boundaries of the Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield.