To the Bitter End

Even as 1865 dawned and the Civil War entered its final, bitter months, few of those living through those turbulent times anticipated the stunning conclusion to the drama that unfolded across the South, as Union armies tightened their hold and moved into position for another strike. At Petersburg, Va., Goldsboro, N.C., Mobile, Ala., and elsewhere, the stage was sent for a final offensive.

On February 3, 1865, on board the River Queen anchored at Hampton Roads, President Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward met with three representatives of the Confederacy: Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, Sen. Robert M. T. Hunter and Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell. Stephens was a political foe of Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy. Hunter, a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, was an experienced Virginia politician. Campbell was a moderate who had initially opposed secession and was a former U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

Upon meeting face to face, the commissioners found they had mutually exclusive goals: Lincoln and Seward insisted on reunion, while the Southerners wanted their independence guaranteed before any further negotiations. Unable to come to an agreement, both sides left the steamer knowing that the war would grind on. The failed attempt at reconciliation had tremendous consequences. From Jefferson Davis on down, Lincoln’s insistence on reunification, rather than the possibility of a treaty for independence, was misinterpreted as a demand for unconditional surrender.

As the news filtered across the South, its implications became clearer to civilians and soldiers alike. Mary Chestnut of South Carolina wrote, “Our commissioners … were received by Lincoln with taunts and derision. Why not? He has it all his own way now.” She was echoed by other female diarists, like one Tennessean teacher, who nonetheless exhorted, “Let the South be extinct before she should be disgraced.”

In the Confederate capital, the Richmond Examiner observed, “New life was visible everywhere. If any man talks of submission, he should be hung from the nearest lamp post.” J.B. Jones, who worked in the Confederate War Department, noted: “…Valor alone is relied upon now for our salvation. Every one thinks the Confederacy will at once gather up its military strength and strike such blows as will astonish the world.” A large public meeting in the city confirmed the attitude of a large amount the civilians: resist at all costs.

The Confederacy, it seemed, was willing to fight on, determined to find resolution on the battlefield rather than at the negotiation table. While it was never stated as official policy, this logic was largely accepted by the government, the military and the public at large. Perhaps too much had happened by February 1865; the war had gone on too long, and too much blood and treasure had been spent to turn back and face defeat.

The Virginia Theater

By the early spring of 1865, the main armies in the East were deeply entrenched in miles of earthworks stretched around and between Petersburg and Richmond. Always endeavoring to stretch his enemy and strike at weak points, Union Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant ordered new assaults to try and break the stalemate by threatening the remaining Confederate supply lines — his eighth overall offensive since taking up position before Petersburg. The first engagement occurred on March 29 at Lewis’s Farm, and victorious Union forces pressed their advantage on March 31 at White Oak Road.

On April 1, Federal troops moved against the small Dinwiddie County crossroads community of Five Forks. Here, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s command overwhelmed the Confederate defenders in front of him and flanked them from the east, routing the division of Maj. Gen. George Pickett. With news of the defeat at Five Forks, Grant ordered assaults along the entire front line for the next day.

At midnight, a massive artillery bombardment began to pound the Confederate lines at Petersburg. Troops of the Union VI Corps moved out at after 4:00 a.m., crossing the no-man’s-land between the lines. The first man into the Confederate trenches was Capt. Charles Gould of the 5th Vermont. Leaping in at the head of his men, Gould received a bayonet to the mouth and cheek from one of the North Carolinian defenders. Gould killed this attacker with his sword and fired his pistol at another Confederate; he continued through this hand-to-hand combat, earning the Medal of Honor for his actions. But Gould was only the first Federal into the breach, and was quickly followed by the rest of the Vermont Brigade; in less than 30 minutes of fighting, a decisive breakthrough had been achieved.

Robert E. Lee, realizing his lines could not hold, ordered Petersburg evacuated, and sent word to Richmond that he intended to move his army westward. The immediate objective for Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia was Amelia Court House, about 40 miles southwest of Richmond. The larger strategy was to link up with the Army of Tennessee, commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, near Smithfield, N.C. Telegrams flashed between the two commanders, and they initiated plans to link their armies.

News arrived in the Confederate capital that Lee’s lines had broken at Petersburg on Sunday morning, April 2. Observant residents were not surprised, for some time there had been rumors of evacuation. Davis, the mayor and city council had already made plans for this contingency, and by afternoon it was unfolding at a steady pace.

Confederate troops began to pull back from the city’s defenses, replaced by local defense forces. Liquor was dumped into the drains, government offices packed up and trains readied to move the government and its finances, archives, and administrative documents to Danville.

Overnight, mobs broke into storehouses, and early the next morning fires were set to destroy supplies of tobacco. Driven by strong winds, the fires spread out of control, destroying the business district of downtown.

From their lines to the east, Union troops saw the red glow in the sky and cautiously crept forward at dawn to find the Confederate lines abandoned. By 7:00, Union troops were marching down Main Street. Their first tasks were to put out the fires, restore order and take control of military property in the city.

For General Lee, the challenge was to extricate the entrenched army from the Richmond and Petersburg defenses, then concentrate the scattered commands. At Amelia Court House, there were supposed to be supplies waiting, but upon arriving on the morning of April 4, Lee found there were none to be had. While waiting for the troops from Richmond to arrive, Lee decided to search the surrounding area.

Thousands of Confederate soldiers, cavalry and wagons deployed and camped around the small village. A.C. Jones of the 3rd Arkansas noted: “The failure to issue rations at Amelia Courthouse, as expected, left us for thirty-six hours without a mouthful to eat.” In the meantime, Union troops closed in from two directions, forcing Lee to keep the army moving.

From Amelia Court House the Confederates retreated south, pursued by the fast-moving Union army, which blocked Lee’s direct route at the small town of Jetersville. Lee was forced to turn west, forever altering his objectives for the campaign. Skirmishing continued daily, as the Union army doggedly pursued. Had Lee attacked to force his way, there could potentially have been a large battle, and perhaps a negotiated surrender, at Jetersville.

But instead, Lee’s army, growing exhausted from constant marching and combat, turned west; its command structure was shattered, its hopes of reinforcement gone and its chances of resupply slipping away. Carlton McCarthy of Cuttshaw’s Battery recalled, “…the march was almost continuous, day and night, and it is with the greatest difficulty that a private in the ranks can recall with accuracy the dates and places on the march. Night was day — day was night. There was no…time to sleep, eat, or rest, and the events of morning became strangely intermingled with the events of evening.”

Virginia artilleryman Percy Hawes agreed, noting “turning night into day renders it almost impossible for me to separate the days. During the next day or two our lives were simply those of marching and fighting and fighting and marching. If we halted at all, it was to fight. There was scarcely an hour in the day that our line was not harassed.”

In the rapidly unfolding sequence of events, Confederate and Union troops each managed to obtain numerical superiority or surprise attacks at different times during the week-long retreat.

Maj. Gen. Edward Ord, commanding the Army of the James, dispatched Union troops on a dangerous mission well ahead of the rest of the army: destroy the river crossing at High Bridge, an enormous railroad bridge over the Appomattox River. Had they succeeded, they would have prevented a large part of Lee’s army from escaping. But Confederate cavalry arrived in time to defend the bridge and attack the two infantry regiments. Outnumbered and overwhelmed, the Federals fell back, with nearly 800 captured, including a brass band.

Yet elsewhere, later that same day at Sailor’s Creek, the Confederate army met a disaster of unprecedented magnitude. Strung out on parallel roads, the vulnerable Rebel force was attacked at three points by infantry and cavalry units. The Confederates tried to stop and fight, but many units were isolated and soon were overwhelmed by the Union troops. It was one of the worst defeats of the whole war, and Lee wondered out loud if his army had been dissolved.

Much of Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Second Corps was captured, along with Ewell himself. In all, Lee lost one-fourth of his army in a single day: about 8,000 men, eight generals (including Custis Lee, son of the commanding general), nearly 50 battle flags and many cannons, wagons, horses and supplies.

On April 8, the Army of Northern Virginia reached the small village of Appomattox Court House. The reserve artillery, moving ahead of the army, passed through the town at midday and continued on two miles farther to Appomattox Station. Late in the afternoon, the infantry followed, and the army camped that night just east of the village. Days of rain and cool weather made the men in both armies miserable.

The army that arrived at Appomattox Court House was physically weak, but not beaten in spirit. The men in the ranks knew their situation was desperate, but they had been in tight spots before. Pvt. A.C. Jones of the 3rd Arkansas recalled, “Up to this time there was not a man in the command who had the slightest doubt that General Lee would be able to bring his army safely out of its desperate straits.”

A short distance from the village was the railroad stop, where Lee’s army was hoping to obtain food. Instead, Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. George A. Custer captured three trains loaded with rations, clothing, ammunition and blankets that were waiting for the Confederates. Beyond the trains at the station sat the Confederate reserve artillery, and Custer quickly had his troopers charge against them.

Much of the Battle of Appomattox Station was fought after sunset, in the growing darkness. The Confederate artillery fired as the Union cavalry charged. One soldier wrote that “it was too dark to see anything” and that “the flashing, and the roaring, and the shouting” sounded “as if the devil himself, had just come up and was about to join in what was going on.”

Union Col. Absalom Randol wrote that “six bright lights suddenly flashed directly before us. A tornado of canister-shot swept over our heads, and the next instant we were in the battery.” After three charges, the Union cavalry captured about 25 Confederate cannons, one-fourth of the army’s reserve artillery. The rest were dispersed and unavailable for further use. Not only did Union forces capture the trains and cannons, but the cavalry also blocked the road, cutting off Lee’s retreat.

At 10:00 p.m., Lee and his exhausted officers held a council of war at his headquarters along the stagecoach road. Acknowledging that Union cavalry was in front of them, the officers agreed they would attack to break through and continue the retreat.

Preparations for the final battle between the major field armies in Virginia began well before dawn on April 9. Confederate Maj. Gen. Gordon’s Second Corps moved through the village to the western side at about 2:00 a.m. His four divisions — Wallace’s, Grimes’s, Walker’s and Evans’s, deployed right to left — were supported by Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s Cavalry Corps, for a total of about 9,000 men awaiting the dawn. Artillery was deployed in the village to support the attack.

At about 7:30 a.m. the attack began when Confederate Brig. Gen. William P. Roberts’s cavalry brigade charged over the rolling ground toward Union Bvt. Brig. Gen. Charles H. Smith’s brigade of dismounted cavalry. The battle flags of the Army of Northern Virginia advanced in combat one last time early on the fog-shrouded morning.

With seven-shot Spencer carbines and 16-shot Henry rifles, Smith’s men could hold out against larger numbers only for a short time, and they fell back as the Confederate infantry advanced. Cavalryman John Bouldin noted that the Confederates charged, “Across the field we dashed right up the guns, shooting the gunners and support down with our Colt’s navies [pistols].”

The outnumbered Federals gave ground slowly, delaying long enough for the infantry of the XXIV and XXV Corps from the Army of the James to arrive. The last gun captured by the Army of Northern Virginia fell into Confederate hands on the ridge overlooking the village.

On seeing some colored troops arrive, Richard Staats of the 6th Ohio Cavalry said, “They had reached this point at daylight after an all night march…and were ready for the business of the day; and the way they looked, and the manner in which they went in at the word of command, was the most inspiring sight I had seen during nearly four years.” Edward Tobie of the 1st Maine Cavalry recalled the feeling of relief at seeing the Union infantry arrive. As he saw them form up alongside the white infantry, he wrote they were “black and white — side by side — a regular checker-board.”

By about 10:00 a.m., the massive Union line was advancing confidently, with the Army of the James coming from the west and joined by the V Corps on the south. Gordon now faced the combined might of more than double his own strength.

To the southeast, along LeGrand Road, Custer’s division of cavalry moved into position. As he rode along the battle line that morning, he was accompanied by a group of aides and orderlies who carried dozens more recently-captured Confederate flags.

The Army of Northern Virginia was surrounded, with the Army of the Potomac behind it and elements of the Army of the Shenandoah and the Army of the James in front. Gordon reported back to Lee that he could not hold and, around 11:00 a.m., a flag of truce went out, seeking a surrender meeting with Grant.

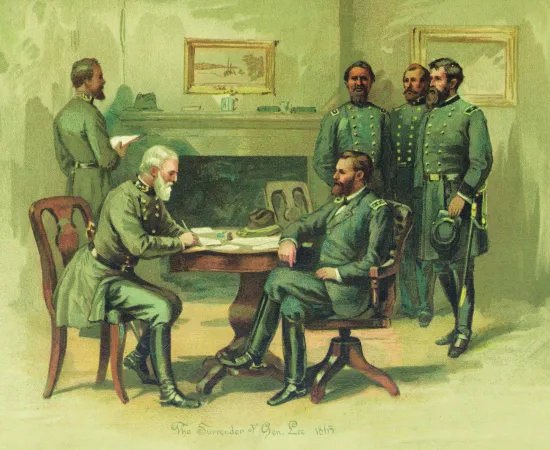

At about 1:30 p.m., Lee and Grant sat down in the parlor of the McLean House to discuss surrender. Historians today know surprisingly little about the important meeting that lasted an hour and a half and had more than a dozen witnesses. Several accounts do exist, but not all agree on the details. What is generally known is this: after some informal discussion, Grant presented his terms —the Confederates would have to surrender their weapons, but would then be allowed to go home.

Lee agreed, asking also that his men be allowed to keep their horses. Grant acquiesced and had his aide Ely Parker write up the terms. Parker had to borrow ink from Confederate aide Charles Marshall, the only other Southern officer with Lee. Parker was a Seneca Indian and had been a friend of Grant’s for several years. Later, when Lee was introduced to Parker, Lee said he was glad to see one true American in the room. Parker replied that “We are all Americans.”

After agreeing on the terms, Lee and Grant both left to return to their armies. Each had much to do. In the meantime, Union officers bought the furniture that was in Wilmer McLean’s parlor, paying him for the tables and chairs that had been used by the generals. One soldier even took a doll that had been in the room; it belonged to seven-year-old Lula, McLean’s daughter.

The next day, a commission formed of three officers from each side met to hammer out the details of the surrender. Union generals John Gibbon, Wesley Merritt and Charles Griffin met with Confederate generals James Longstreet, John Gordon and William Pendleton. Thus the McLeans’ parlor was not only the site of Lee and Grant’s meeting, but also of the commission that drew up the formal proceedings of the surrender.

These proceedings stipulated that the Confederate infantry would march in and surrender their arms, that officers and men could keep their personal horses and property (including officers’ swords) and that the surrender would apply to all Confederate troops within a 20-mile radius of Appomattox.

It was also agreed that the surrender would occur over the next three days: the cavalry that day, followed by the artillery on April 11 and the infantry last on April 12.

Most of the Confederate cavalry had actually gotten away during the fighting on the morning of April 9, and only 1,559 cavalrymen remained in the camp above the Appomattox River. Bvt. Maj. Gen. Ranald MacKenzie received orders to meet the Southern cavalry on the road north of the village, where he would collect their sabers, firearms and accoutrements.

For the artillery, it was simply a matter of unhitching the guns from the horses and leaving them in the road just west of the village. In fact, the Confederates’ animals were so worn and exhausted that the guns could not have been moved anyway. Although Lee’s army had suffered heavily in infantry losses, the Confederates still had more than 60 cannons in their arsenal.

The largest part of the surrender — and by far the most symbolic — was the stacking of arms scheduled for the morning of April 12, four years to the day after the initial shelling of Fort Sumter. In the meantime, Union soldiers set up printing presses in the Clover Hill tavern and began churning out parole passes for the Confederate soldiers. They worked around the clock to crank out 28,231 paroles on hand-crank printing presses in 24 hours.

Each parole was a pass stating that the man carrying the document had surrendered. If a parolee was stopped by Union soldiers on his way home, the former Confederates could show the pass as a guarantee of safe passage on their journey. In addition, Grant ordered that the paroles could be used at any Union army supply station to obtain food or to secure passage on Union military trains and ships. For former Confederates attempting to reach distant places like Texas or Mississippi, this was welcome news.

Appomattox set the tone for how the war would end: Confederates would be paroled and assisted on their journey home. But it was unique among the various surrenders in that there was a final decisive battle, placing the armies in physical contact so that Union officials could oversee the proceedings. All surrenders that followed were more chaotic.

When Lee surrendered to Grant, he only relinquished the Army of Northern Virginia. Yet elsewhere, Union and Confederates alike saw this as the symbolic end of the war. Each Confederate army had to surrender individually, and some still held out hope of resistance, including both large forces and isolated garrisons scattered across the Deep South.

North Carolina Falls to Sherman’s Juggernaut

To the south, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston commanded troops from a mixture of various departments — including the remnants of the Army of Tennessee, troops transferred from the Army of Northern Virginia, units from the Department of the Carolinas and the North Carolina Junior Reserves — and was charged with defending North Carolina against the nearly inexorable force of Maj. Gen. William Sherman’s column, fresh from their march through Georgia and South Carolina.

The first battle between these forces took place at Averasborough, near Fayetteville, on March 15–16. Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s Union cavalry found Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s corps and Wheeler’s dismounted cavalry deployed across the Raleigh Road. After testing the Confederate defenses, Kilpatrick withdrew and called for infantry support. Overnight the XX Corps arrived, attacking at dawn.

The Federals advanced on a wide front, driving the Confederates back, but were stopped by the main Confederate line and a counterattack. At mid-morning, the Federals renewed their advance with strong reinforcements and drove the Confederates from two lines of works, but were repulsed at a third line. Hardee retreated during the night, having held up the Union advance for nearly two days.

Johnston planned a major effort at Bentonville, taking advantage of a gap between the wings of Sherman’s forces. Late in the afternoon of March 19, Johnston attacked, crushing the Union XIV Corps. Only strong counterattacks and desperate fighting south of the Goldsborough Road blunted the Confederate offensive. Some Union troops were briefly surrounded and attacked from both sides. Elements of the XX Corps arrived and joined the fight. Five Confederate attacks failed to dislodge the Federal defenders, and darkness ended the fighting. During the night, Johnston contracted his line to protect his flanks with Mill Creek to his rear.

The next day, Union reinforcements arrived, but fighting was sporadic. On March 21, Johnston remained in position while he removed his wounded, and skirmishing soon flared along the entire front. In the afternoon, Bvt. Maj. Gen. Joseph Mower’s Union division moved along a narrow trace across Mill Creek toward Johnston’s rear. At the last moment, Confederate counterattacks stopped Mower’s advance, saving the army’s line of communication and retreat.

Johnston pulled back toward Raleigh, ahead of Sherman’s advance. News of Richmond’s fall was a tremendous blow that put Johnston on the road to link up with Lee somewhere near the Virginia-North Carolina line. However, rumors of Lee’s surrender soon began to filter through the army; disbelief turned to shock when confirmation arrived.

The Army of Tennessee retreated through Raleigh, abandoning the capital without a fight, and continued marching west through Hillsborough and Chapel Hill toward Greensboro, a major supply and railroad center. Johnston knew that President Davis and the Cabinet were on their way from Danville, and he looked to meet with them to decide the future of the struggle. At the resulting conference, Johnston obtained permission to meet with Sherman and discuss terms.

The two generals met at an unassuming farmhouse near Durham. The owners, James and Nancy Bennett, had endured the tragedies of war, losing two sons to the conflict — Lorenzo died in the ranks of the 27th North Carolina and Alphonzo, succumbed to illness, likely at the home — as well as their son-in-law, Robert Duke of the 46th North Carolina. The Bennetts obliged the officers and waited in the kitchen with their daughter Eliza and her first-born son while the generals used the home.

At this April 17 conference, the generals agreed that they must restore peace as quickly as possible, especially in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Their meeting produced sweeping terms that stopped the fighting and allowed for the recognition of existing state governments.

But Sherman had overstepped his bounds, and President Andrew Johnson and the U.S. Congress rejected the generous terms he had offered. Grant conveyed the news to Sherman in person, and Sherman and Johnston met again, using the same terms as Appomattox. This second meeting took place on April 26.

Johnston’s surrender included not only the Army of Tennessee, but also the Department of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, along with many garrisons, detachments and scattered commands in those four states. Altogether, it included 89,270 men.

The final terms allowed the men of the Army of Tennessee to keep their personal property and use the army’s wagons and horses to return home. It also stipulated that the Union army would send rations to Southern camps around Greensboro, and the Federal navy would assist those needing transportation to the Gulf States. The men were to stack their rifles and park their artillery where they were camped; battle flags were to be left behind as well. With limited Union troops present to oversee this process, the Southerners were to carry out their own surrender.

The End in Alabama

As news of Lee’s and Johnston’s surrenders spread, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, commanding the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana, faced the inevitable. He resolved to seek honorable terms, “whilst still in my power to do so.” He viewed the surrender with his troops in mind — to “preserve their honor and best protect them and the people.”

On April 29, Union Bvt. Maj. Gen. Edward Canby and an escort of 2,000 cavalrymen moved north from Mobile and waited at the Jacob Magee House, near the Kushla Station along the Mobile and Ohio Railroad line. The meeting went quickly; Canby offered Taylor the same terms as those presented by Sherman at Bennett Place, leaving Taylor no room to bargain. Within 10 minutes, they emerged from the parlor with a ceasefire agreement. Champagne was on hand, courtesy of Canby, and Taylor noted that the popping corks were “the first agreeable explosive sounds I had heard for years.”

Sadly, the celebration was premature; two days later, the generals learned that the United States government had disapproved the terms initially offered to Johnston and subsequently to Taylor. Canby apologetically notified Taylor that their ceasefire ended in 48 hours.

The generals met for a second time at Citronelle on May 4, and Taylor wrote afterward that the terms offered by Canby were “consistent with the honor of our arms.” The terms produced were nearly identical to those of Appomattox and Greensboro: officers would retain their side arms and men with horses could keep them. Confederate soldiers would be paroled, and Taylor would retain control of railways and river steamers to help them get home. Additionally, Union naval forces and Union-controlled railroads would also transport men to the nearest practicable point close to their homes. By the authority of the United States, the Southern soldiers were not to be disturbed “so long as they continue to observe the condition of their paroles.”

Simultaneously, Union troops throughout the South were eagerly seeking out the fugitive Confederate cabinet, driven, in part, by the hefty reward offered for the capture of Jefferson Davis. These officials had boarded trains in Richmond on April 2, meeting intermittently as they fled from the advancing Union armies. At Washington, Ga., on May 5, 14 members of the cabinet met for the final time and, bowing to the undeniable truth of their situation, officially dissolved the Confederate government.

A General Without An Army: the Trans-Mississippi

While these events unfolded in the east, troops in the vast Trans-Mississippi Department, headquartered in Shreveport, La., soldiered on under very different conditions. Robberies, desertion and violence were rampant in the camps, so much so that the department’s commander, Confederate Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, and his staff did not go out at night. Several high-ranking Confederate officers secretly discussed arresting Smith (and any cooperative government officials) in the event that he follow the lead of Eastern commanders and surrender the department. This proved unnecessary, as, Smith hoped to move his headquarters to Texas and either continue fighting or continue to Mexico.

On May 9, Smith wrote to the governors of Texas, Arkansas and Missouri, requesting a meeting to discuss his future actions. Their response was one of two crushing blows received by Confederate forces still in the field on May 10. The governors advised Smith to “disband his armies in the department; officers and men to return immediately to their former homes, or such as they may select … and there to remain as good citizens, freed from all disabilities, and restored to all the rights of citizenship.” That same day, hundreds of miles to the east, Confederate president Jefferson Davis — undisguised, despite popular legends to the contrary — was captured at Irwinville, Ga. Davis spent the next two years imprisoned at Fortress Monroe, Va., although he never faced trial on rumored charges of treason.

Still, the conflict was not over. The Civil War’s last land battle was fought at Palmito Ranch, Texas, on May 12. In a badly coordinated operation, Union forces were scattered and defeated by Texas troops along the Rio Grande. Native, African and Hispanic Americans were all involved in the fighting.

Although Smith notified Union forces that the civilian governors had called for an end to the war, provided “certain measures which they deem necessary to the public order and proper security of the people” were met by the U.S. government, he was careful to note that this was despite the fact that his army was “well appointed and supplied, not immediately threatened, and with its communications open.”

His own hopes for continued resistance undimmed, Smith began the process of moving his headquarters to Houston, where it would be safer from attack. But after the commander’s departure from Shreveport, the remaining troops began to desert in droves, a breakdown that soon spread to the garrisons in Texas. In Houston, Austin, and San Antonio, shops were looted, supplies stolen from government warehouses, and disorganized troops left their posts.

Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, now in command at Shreveport, saw the writing on the wall, and on May 26, he arrived at New Orleans to surrender to Union Maj. Gen. Peter Osterhaus, representing Canby. The terms were identical to those of Appomattox, the only ones Union commanders were authorized to accept. When Smith reached Houston the next day, he learned that his war was over, although he did not surrender formally until June 2, at Galveston. Given the changed nature of the conflict, very few of the approximately 17,500 troops remaining in the Trans-Mississippi Department received the formal paroles that were commonplace in earlier months.

Last To Go: Indian Territory

In the spring of 1865, the situation in the Indian Territory was fully stalemated. Then, on May 28, news arrived of the surrender of the Confederate Department of Trans-Mississippi, which included the Indian Territory. General and Cherokee chief Stand Watie intended to keep fighting, but the tide was against him. Other Indian chiefs who disagreed with continuing to fight convened the Grand Council on June 10 and passed resolutions calling for Indian commanders to stop fighting.

Knowing of the unrest among the tribes, Union Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge appointed Lt. Col. Asa C. Matthews to negotiate a peace with the Indians. Since each Indian nation had signed its own treaty with the Confederacy, it was necessary for them to surrender separately from other Southern forces. Thus, Governor Winchester Colbert of the Chickasaws surrendered to Matthews on June 14, followed by Chief Peter Pitchlynn surrendering Choctaws and Caddos June 19.

Four days later, on June 23, 1865, Watie surrendered the First Indian Cavalry Brigade, consisting of Cherokee, Creek, Seminole and Osage fighters, 12 miles west of Doaksville to Lt. Col. Asa C. Matthews and Adj. William H. Vance. When the Cherokee general handed over his sword, his was the last Confederate military force to formally surrender.

On September 14, representatives of the various tribes met with federal officials at Fort Smith. The delegates tried to heal the wounds and divisions of the war, but were not entirely successful. In the resulting treaty, the Indians affirmed their loyalty to the United States, renounced all treaties with the Confederacy and agreed to end slavery (admitting former slaves as tribal members). However, tensions between the pro-Union and pro-Confederate factions of the tribes were not easily resolved and lingered for some time.

We have a chance to save these critical pieces of history at Gaines' Mill, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox Court House for just a fraction of their full...

Related Battles

121

1,000