Bitters, Blockades, and the Bluegrass State: Bourbon and the Civil War

“I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game… We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.”

– Abraham Lincoln in letter to O.H. Browning, September 22, 1861

Today, bourbon can be defined as broadly as any whiskey made in the United States, but, in the 19th century, bourbon referred to a geographically specific recipe. During the Civil War, bourbon was made of a mash containing at least 51% corn and aged in charred barrels. It also had to be made in Kentucky. As a result, the story of Kentucky in the Civil War is also the story of bourbon.

The newly-formed Confederate States of America had its eye on the Bluegrass State due to its resources and the strategic value of having a northern border at the Ohio River, while the Union valued Kentucky for its population size, agricultural production, and sway on other border states—those with slavery but remained in the Union. As the country divided around Kentucky, those within the state divided along sectional loyalty lines, as well. So, instead of choosing one over the other, Kentucky declared neutrality.

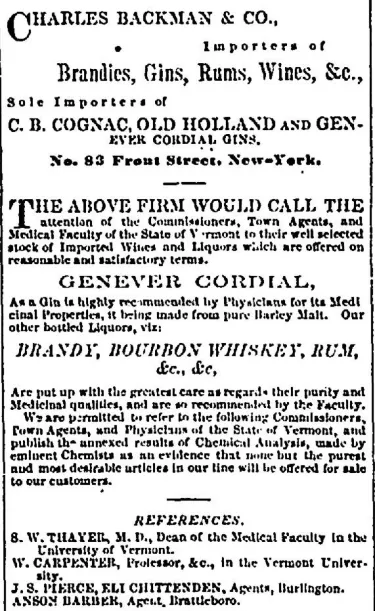

This neutrality was short-lived, however, as the state reluctantly called for Union support following an unsuccessful expedition and occupation of Columbus, Kentucky by Confederate forces under Leonidas Polk in September 1861. Now, Kentucky’s men, resources, and bourbon, were available to the Union and cut off from the Confederacy. Unlike other forms of whiskey, bourbon’s aging rendered passable substitutes very difficult to distill. While merchants may have sold “bourbon” that was really another form of whiskey, a diluted form of bourbon, or something else entirely, the number of advertisements in period newspapers assuring the purity of their bourbon indicates that this was a well-known—and therefore more difficult—trick.

The aging process made true bourbon a largely unique luxury of the Civil War-era. First, the investment of time and space that aging required made it a good produced mostly by wealthier distillers for richer consumers. Strangely, while long mid-nineteenth century travel times posed issues for most of the food in this era, extra time spent in transit only increased bourbon’s value. The Union blockade that prevented all “foreign” goods from entering the Confederacy resulted in dangerous, smuggling operations that brought bourbon to Confederate markets by land or through the blockade—a trip that would have brought the drink from Kentucky to a warehouse in the Caribbean, and then back to the guarded coastline of the South! At least one account by Union blockaders recalls barrels of bourbon floating away from the wreck of a beached blockade runner. Some bourbon did make it to at least one Southern city: stores in Richmond, Virginia, advertised the sale of barrels of bourbon whiskey throughout the war.

But why put so much effort into acquiring a specific type of whiskey? Bourbon was valuable not just as an intoxicating beverage, but also as a medical stimulant. While rum and brandy were the favored stimulants of doctors, newspapers of the period specify that in the absence of either of these liquors, bourbon made an acceptable substitute. Bourbon was also a crucial ingredient in bitters, a mixture of herbs, plant matter, and alcohol designed to cure all manner of illnesses. In 19th century medicine, bourbon had important curative qualities that distinguished it from other types of whiskey. Unfortunately for Confederate doctors and their patients, bourbon came to be extremely hard to come by as the war progressed. In fact, bourbon became so scarce that its price hit $40 per gallon in Richmond, more than eight times that of bourbon sold in Northern cities.

The end of the war brought bourbon back into Southern markets, where its price fell back to those of other forms of corn whiskey. By the late 1860s, it was easier to find bourbon in many Southern cities than in Northern ones. A century later, it grew to become a source of national pride when Congress declared it to be a distinctly American drink. At the same time, the bourbon company Old Crow, established in 1835, ran a series of advertisements showing their bourbon being consumed by famous Americans throughout the nineteenth century. By highlighting well-known names such as Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, representative of New England Daniel Webster, Texan hero Sam Houston, and Californian novelist Jack London, Old Crow reinforced bourbon’s place in American society—regardless of region. Today, despite its renown and expanded definition, bourbon continues to be a part of Kentucky’s history and future. There are now some 70 distilleries in the state that continues to produce 95% of the world’s supply, ensuring that stories of bourbon and Kentucky remain intertwined.