Situated between three slave states and three free; connected by railroad arteries into Tennessee and Ohio; and bounded by rivers accessing the Deep South and the East Coast, Kentucky was where North and South converged — where, as historian Bruce Catton said, they “touched one another most intimately.” But when those two philosophies collided over slavery in 1860, the impact shook Kentucky to its core.

The presidential election of 1860 deepened a growing chasm between divided Kentuckians. Southern Democrat and Kentucky son John C. Breckinridge won 36 percent of the state’s vote with a pro-slavery platform and Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas, champion of popular sovereignty, received 18 percent, while Constitutional Unionist John Bell, who stood simply for preserving the Union, carried the state with 45 percent. Abraham Lincoln, promoting Republican opposition to slavery’s expansion swayed less than one percent of Kentucky voters. But when Lincoln’s victory brought secession and war, the state was too divided to rally behind either side. Torn geographically, ideologically, economically, politically and militarily between North and South, Kentucky was the physical embodiment of the Civil War era’s “brother against brother” strife.

Slave or Free

Slavery was first introduced to Kentucky during its territorial days, and for nearly the first 40 years of its statehood, Kentucky’s population of slaves grew faster than that of whites. By 1830, slaves constituted 24 percent of all Kentuckians, although this ratio dropped to 19.5 percent by 1860. Slave owners in Kentucky numbered more than 38,000 in 1860, the third highest total behind Virginia and Georgia. Like most slave states, Kentucky was not a land of large plantations: 22,000 of its slave holders — or 57 percent — owned four or fewer slaves.

Kentucky’s most ardent proponents of slavery came from the state’s south and west sections, where the lifestyle most resembled that of the Deep South. The primary differentiation came in terms of crop distribution. In the Deep South, slavery-based cash crops such as cotton, rice and sugar were the norm; in southern and western Kentucky, tobacco was the cash crop, accounting for one quarter of the nation’s tobacco output and requiring nearly year-round labor to produce. Another prominent crop was hemp, the growing of which involved the hardest, dirtiest and most laborious agricultural work in the state, making it desirable for slave labor. Together, tobacco and hemp firmly bound southern and western Kentuckians to the preservation of slavery.

In the north and east, Kentuckians were ideologically and economically moving away from slavery. Economically, the area was diversifying. More and more of these Kentuckians broadened their traditional tobacco-and-hemp livelihoods by cultivating grains and cereals, breeding horses and livestock and manufacturing goods. By 1850, they had given Kentucky the South’s second broadest economic base. Generally, a more diversified economy meant less reliance on slavery, which helps to explain Kentucky’s rising emancipation ideology. Already, diversified Kentucky had a profitable market in the excess slaves sold to the Deep South. It was only a step further, then, to support emancipation, which called for a gradual and compensated end to slavery.

A third faction of Kentuckians was ambivalent about slavery. Although not economically bound to the institution themselves, they justified it for several reasons. Some called it a “necessary evil” for life in an agricultural state. Others, prejudiced against or wary of a large free-black population, regarded slavery as a means of control.

Kentucky v. Kentucky

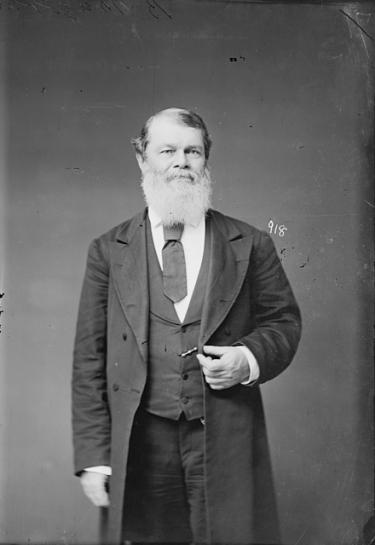

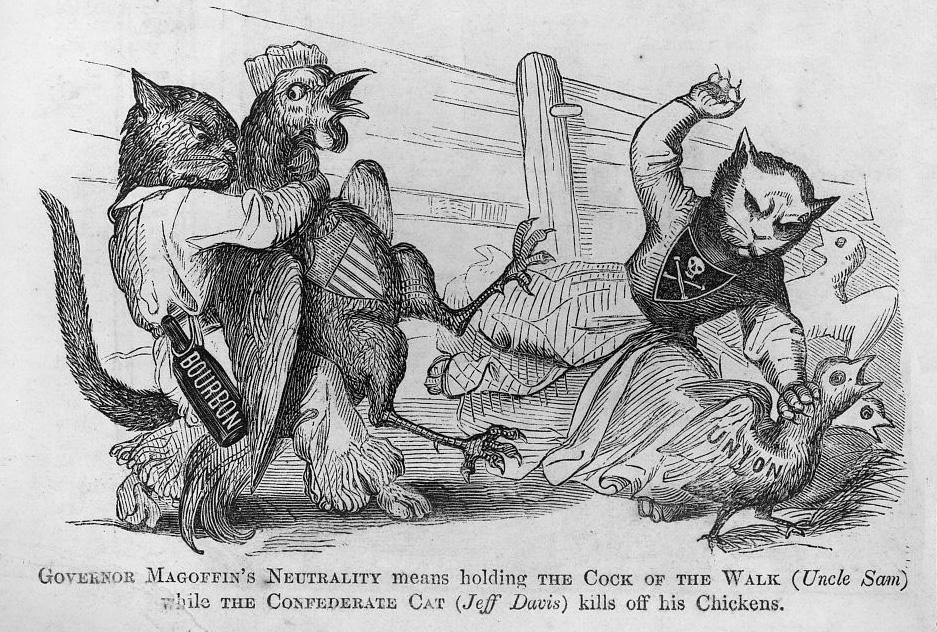

As one southern state after another seceded between December 1860 and May 1861, Kentucky was torn between loyalty to her sister slave states and its national Union. One month after the opening shots at Fort Sumter in April 1861, Gov. Beriah Magoffin issued a formal proclamation of neutrality and advised Kentuckians to remain at home and away from the fight. Although Magoffin did not believe slavery was a “moral, social, or political evil,” he opposed immediate secession on two fronts. First, he believed the sectional differences could be worked out through mediation. Second, he feared an invasion of Kentucky if the state seceded.

At the individual level, Kentucky Unionists, largely those who supported Bell and Douglas in the 1860 election, favored neutrality because they disapproved of both southern secession and northern coercion of southern states. Confederate sympathizers backed neutrality because they feared that if Kentucky chose a side, she would choose the Union.

But neutrality in principle was much less complicated than neutrality in practice. Army recruiters from both sides entered Kentucky to enlist volunteers, and each army amassed troops along the state’s borders. Within Kentucky, the rival factions organized militias — Confederate sympathizers called themselves the State Guards, while Unionists became the Home Guards.

Lincoln, meanwhile, governed Kentucky with a light hand during her neutrality. He worried that any demonstration of force would prompt her secession. For a time, Lincoln even turned a blind eye as Kentucky allowed horses, food and other military supplies and munitions to enter the Confederacy. But just a month after Magoffin proclaimed neutrality, Kentuckians delivered important political victories to the Unionists, when those candidates won nine out 10 of the state’s congressional seats. Later, on August 5, Unionists also won control of the state legislature. Their success was partially due to outspoken claims that the South only wanted Kentucky to stand between it and danger. However, the success was also bolstered by a boycott by pro-Confederates, who refused to participate in elections for a government they did not recognize.

In response to the Unionists’ growing political power, the state’s Southern sympathizers formed a rival Confederate government. On November 18, 200 delegates passed an Ordinance of Secession and established Confederate Kentucky; the following December it was admitted to the Confederacy as a 13th state. The state capital was at Bowling Green, and George W. Johnson — who only supported Kentucky’s secession because he hoped the new balance of power would end the war — became governor. Governor Magoffin eventually resigned and cast his lot with Confederate Kentucky, as did John C. Breckinridge.

Kentucky’s dual governments and military forces caused many divisions between Kentucky families. Kentucky-born statesman John J. Crittenden’s son George was a general in the Confederate Army; his son Thomas was a general for the Union. Robert Breckinridge, John C. Breckinridge’s uncle, had two sons fighting for the North and two for the South. Three grandsons of the late Kentucky statesman Henry Clay fought in Union blue while four fought in Confederate gray.

In total, about 100,000 Kentuckians served in the Union Army. After April 1864, when the Union Army began recruiting African American soldiers in Kentucky, almost 24,000 joined to fight for their freedom. For the Confederacy, between 25,000 and 40,000 Kentuckians answered the call of duty. Their most celebrated unit was the First Kentucky “Orphan” Brigade. The Orphans fought hard on many western battlefields, and their heavy losses — especially in commanders — may have led to their nickname. In mid-1862, Benjamin H. Helm took command of the brigade and led it until his death the following year at the Battle of Chickamauga. Helm was President Lincoln’s brother-in-law.

Partitioning the State

For the first few months of war, the Union and Confederate armies stayed out of Kentucky. That changed when Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk ordered a Confederate invasion of Columbus for September 4, 1861. Columbus was a port town on the Mississippi. Its high bluffs and railroad terminal made it valuable militarily — so valuable that Polk seized it to preempt a Union occupation. Two days later, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant responded by occupying Paducah and then Smithland. Because the Confederates invaded first, they were branded the aggressor. Although Governor Magoffin called for both sides to leave Kentucky, the Unionist legislature only asked the Southerners to withdraw. All pretenses of neutrality were gone.

After staking their initial claim, Union soldiers came down from Cincinnati to take control of northern Kentucky, while Confederates moved in through Tennessee to claim southern Kentucky, including the Cumberland Gap situated near the convergence of Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia. With nearby railroads and access to ardently Unionist East Tennessee, the Gap was a strategically important site, but the ambitious Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer, who seized the Gap, was discontent to remain there. Accordingly, he planned to extend his line further north and west into central Kentucky. As Zollicoffer and his men moved north along the Wilderness Road, they encountered a Union force sent to halt their progress. On October 21, the two sides clashed at Camp Wild Cat, and the Union troops sent Zollicoffer backtracking in defeat.

Despite his defeat, Zollicoffer did not abandon his goal. But instead of heading north, he turned his attention westward, and in November, encamped for the winter at Mill Springs, a strong position on the Cumberland River. By January, Union troops under Brig. Gen. George Thomas advanced to defeat Zollicoffer’s Confederates, now commanded by Kentucky native Maj. Gen. George Crittenden. Fearing Union reinforcements, Crittenden attacked on January 19, 1862. Despite some initial Confederate success, Thomas’s troops held firm. By the battle’s end, the Confederate defeat was so complete that Crittenden’s men retreated all the way to Tennessee; Zollicoffer had been killed in the action.

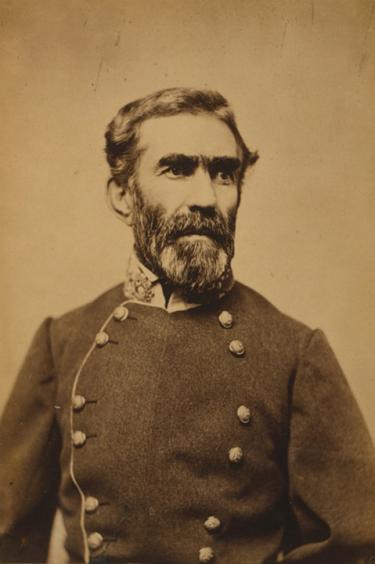

After this loss, Confederate operations in the Western Theater went from bad to worse. Soon after the Confederate retreat, Union troops captured Forts Henry and Donelson, just south of the Kentucky border. These forts provided control of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers and allowed Union troops to outflank Columbus, sending the remaining Confederate forces retreating from Kentucky. By summer, the Federals controlled all of Kentucky, most of Tennessee and northern Alabama. In a bold attempt to push Union troops out of the South and win back Kentucky, Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg and Maj. Gen. Kirby Smith commenced a grand offensive.

Moving into Kentucky from East Tennessee, Smith and his men marched toward Lexington. On the way, they encountered William Bull’s raw Union recruits near Richmond. In three separate engagements on August 30, Smith’s veterans routed their opponents and captured an astonishing 4,000 soldiers. Meanwhile, Bragg entered Kentucky via the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, then marched east to Bardstown. Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell pursued him with a larger force. On October 8, the two armies crossed paths at Perryville when Bragg ordered a portion of his men to attack what he thought was a small Union force. Bragg’s men achieved remarkable success but later that evening Bragg, outnumbered and in a precarious position, fell back. Fearing the destruction of his army, Bragg ordered a full-scale retreat from Kentucky less than a week later.

After Bragg’s retreat, Kentucky was in Union hands for the remainder of the war, but Confederate raiders continued to wreak havoc and foster division behind enemy lines. One of the most famous raiders operating in Kentucky was Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. Though born in Alabama, Morgan spent most of his life in Kentucky. He had no formal military education but was immensely successful with hit-and-run strikes to disrupt the Union supply line, occupy Union troops away from the front and secure supplies for the Confederacy.

In December 1862, Morgan undertook his famous Christmas Raid. During this two-week period, he rode 400 miles in central Kentucky, tore up 20 miles of railroad, destroyed an estimated $2 million worth of supplies and took nearly 1,900 prisoners. Another of Morgan’s exploits was less successful — his Kentucky- Indiana-Ohio Raid of July 1863. Granted permission to raid Louisville but not to cross the Ohio River, Morgan disregarded orders at great cost to his men. Morgan was captured in Ohio (though he later escaped), and only a few hundred of his more than 2,400 men made it home.

Invasions, raids and guerilla warfare worsened toward the war’s end as defiant Confederates rebelled against the Union presence in their state. When Confederate armies finally surrendered in April 1865, one Kentuckian recalled that “pandemonium broke loose and everyone acted as if the world was coming to an end.” But the South’s surrender did not unite a divided Kentucky. Many Kentuckians balked at freedom for blacks, and hatred often prevailed. For the first five months after the Confederate surrender, U.S. troops imposed martial law in Kentucky. Even after the military left, the state was a violent place through the 1860s and beyond. The war’s political aftermath also left the state deeply divided as former Unionists, former Confederates and former Whigs fought bitterly for power.

Post-war Kentucky needed healing. Families, communities and entire regions of the state had been ripped apart by the war, and more than simple animosity was prevalent throughout. Yet as the North and South healed their wounds and settled their differences, surely Kentucky would, as well. For in Kentucky, where such division had resulted from North and South’s convergence, there was also great promise, because, as historian Bruce Catton wrote, “where North and South touched one another most intimately” was also where they “came closest to a mutual understanding.”

Related Battles

4,211

3,401