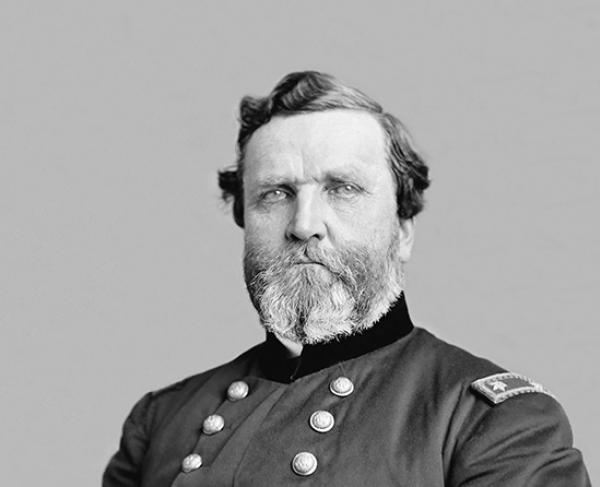

George Thomas

Although only twice in chief command of a field army during battle — Mill Springs, Kentucky, near the war’s beginning, and Nashville, Tennessee, near its end — Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas played a significant role in shaping the war beyond the Appalachian Mountains.

Thomas was born into a slaveholding family on a Virginia plantation just north of the North Carolina border in 1816. At the age of 20, he received an appointment to West Point, where his significantly younger peers called him “Old Tom.” He graduated in 1840, 12th in his class, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in Company D, 3rd U.S. Artillery.

During the Mexican-American War, Thomas served with distinction alongside fellow artillerist Braxton Bragg, whom he would face across many battlefields two decades later. After the close of hostilities, Thomas was appointed instructor of cavalry and artillery under academy superintendent Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Thomas did not resign his commission in the U.S. Army, despite the offer of several prominent commissions in the Confederate army. His decision to remain loyal to the Union created a deep rift with his family, one that would not heal in his lifetime. Thomas’ comrades and former students reacted no less vehemently: former star pupil and fellow Virginian J.E.B. Stuart wrote to his wife, “I would like to hang, hang him as a traitor to his native state.”

Although an earlier back injury made his physical movements deliberate, Thomas possessed deep tactical understanding of warfare, attributable to having served in all three branches of the military. During the Battle of Chickamauga, he held his position, rallying broken and scattered units to prevent a hopeless rout. Future president James Garfield reported to Army of the Cumberland commander, William Rosecrans, that Thomas was “standing like a rock,” and the name stuck; the “Rock of Chickamauga” was soon elevated to command and rose to greater fame.

Following the end of hostilities, Thomas commanded the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky and Tennessee, and at times also West Virginia and parts of Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama, where he worked to uphold the rights of freedmen against abuses. In 1869, he requested a transfer to command the Department of the Pacific in San Francisco, where he died the following year of a stroke.

Thomas’s innate desire for privacy — he destroyed his private papers to keep his life from being “hawked in print” — and an early death prevented him from publishing his memoirs, a popular genre for former generals in the 1870s and 1880s, and defending his legacy from fellow commanders looking to promote their own at others’ expense. William T. Sherman, a lifelong friend since their West Point days, however, called Thomas’s services throughout the war “transcendent” and listed him along with Ulysses S. Grant as the heroes deserving “monuments like those of Nelson and Wellington in London, well worthy to stand side by side with the one which now graces our capitol city of George Washington.”

Today, an equestrian statue of the Rock of Chickamauga stands in downtown Washington D.C.’s Thomas Circle.