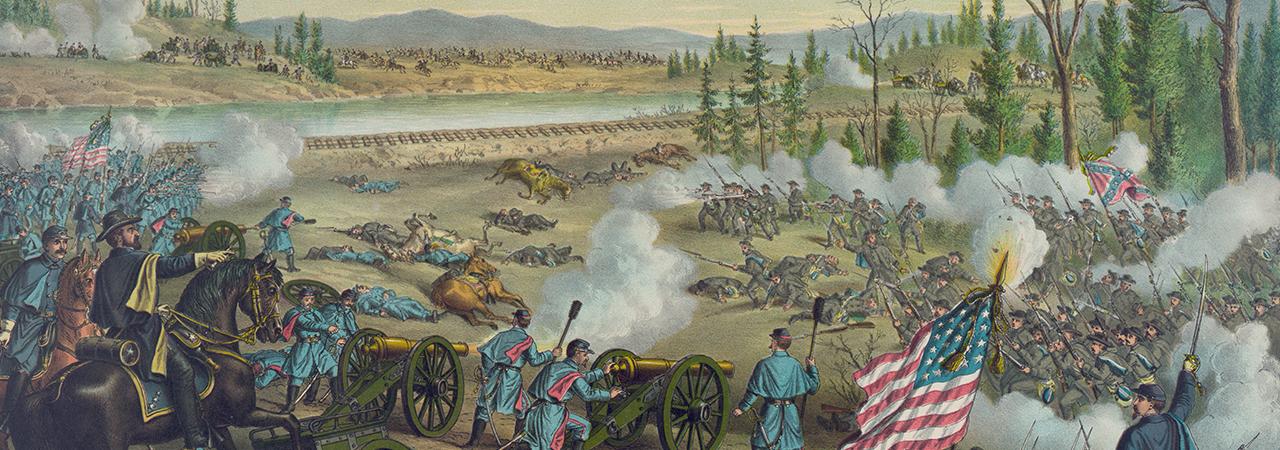

Stones River

Murfreesboro

Rutherford County, TN | Dec 31, 1862 - Jan 2, 1863

The Union squeaked out a victory in a bloody conflict at Stones River, which boosted morale in the North and gave the Federals control of central Tennessee. Of the major battles in the Civil War, Stones River had the highest percentage of casualties on both sides.

How it ended

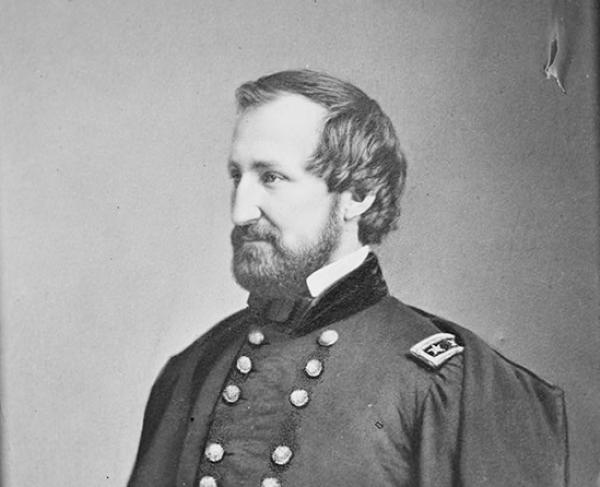

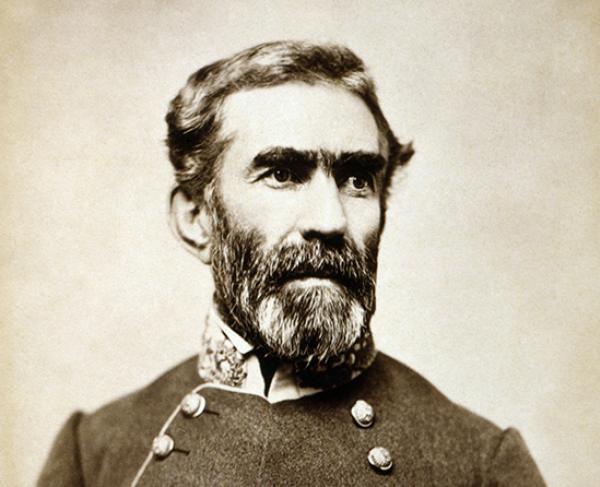

Union victory. An uncoordinated attack by Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of the Tennessee worked in favor of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland. The Federals held their own but at a great cost. Rosecrans’s men were so battered they would not campaign for another six months.

In context

An extended lull fell over the western armies following the Battle of Perryville in the fall of 1862. Although victorious, Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell lacked the initiative to follow up on his victory and was soon relieved of command by President Abraham Lincoln. Major General William S. Rosecrans assumed command of the Army of the Ohio and reconstituted it as the Army of the Cumberland. On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and the president expected his generals to bring home as many victories as possible by January 1, 1863—when he would officially sign the act—to give this new measure backbone.

The day after Christmas 1862, Rosecrans's Army of the Cumberland departed Nashville with 44,000 men, marching toward Confederate general Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee at Murfreesboro, 30 miles to the south. The overly cautious and plodding Rosecrans left some 40,000 men in and around the Tennessee capital to guard his communication and supply routes, an advantage for Bragg.

Rosecrans and Bragg’s forces clashed at Stones River as 1862 ended. Mistakes on the Confederate side led to a tactical Union victory, but casualties were high, and it was months before Rosecrans’s Federals would be battle-ready again.

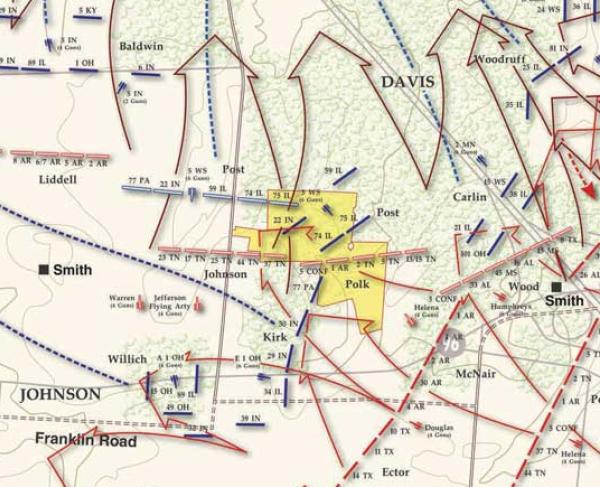

On the evening of December 30, the two armies gather on the banks of Stones River within 700 yards of one another. Rosecrans’s army on the northwest side of the river is organized into three wings with three divisions each. Bragg’s 35,000 men are arranged into two corps of infantry.

Both commanders formulate a nearly identical battleplan for December 31: strike their opponent’s right flank. While a portion of Rosecrans’s army has to cross the river to accomplish this goal, the Confederates face no such problem.

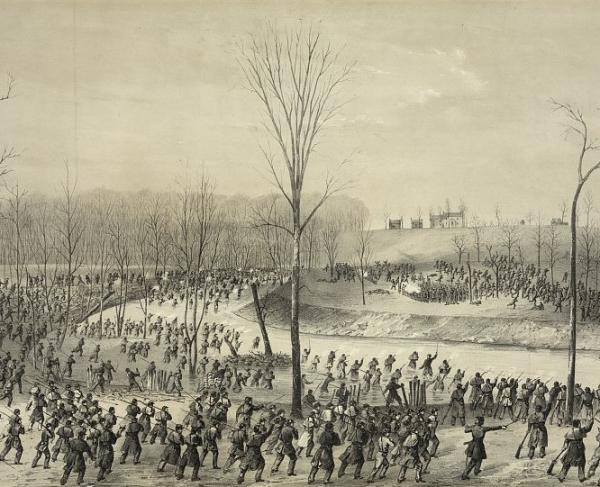

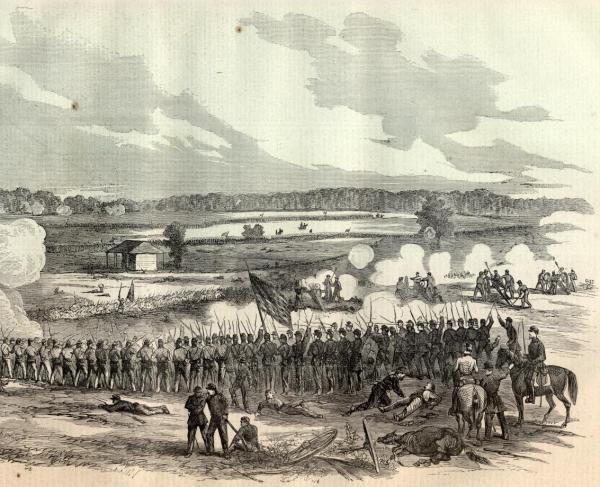

December 31. At 6:00 a.m. on a bitterly cold day, Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps surprise the Federals and smash into the Union right flank. The Federals are sent reeling backward some two and a half miles to the Nashville turnpike and railroad, and many Union cannon fall into Confederate hands.

The most intense combat of the day occurs in a dense forested area, later dubbed “Hell’s Half Acre” by the men who fought there. Despite the lethal conditions, Chaplain John Whitehead of the Fifteenth Indiana carries wounded off the battlefield, a brave and selfless act that later earns him the Medal of Honor.

Federal troops manage to hold critical ground that includes the railroad and turnpike. The stout resistance of Maj. Gen. George Thomas’s wing, the omnipresent Rosecrans, and the failure of Bragg’s army to coordinate its attacks result in significant casualties but save the Army of the Cumberland from utter destruction. By the evening of December 31, the Army of the Cumberland is cornered against Stones River, and Bragg crows to Richmond, “God has granted us a happy New Year.”

January 1. A hiatus gives both sides time to shore up their battle lines. Rosecrans shifts men eastward across the river and establishes a formidable line along a hilltop. Bragg responds by ordering Maj. Gen. Breckinridge to charge this new position.

January 2. About 4:00 p.m. Breckinridge reluctantly sends his men forward. Approximately 5,000 Confederates cross half a mile of open field, torn from front and flank by massed artillery, and nearly break the Union line in a desperate charge. The Federal line is once again salvaged, this time due to the courageous efforts of Capt. John C. Mendenhall, who positions nearly 50 cannon hub-to-hub and blasts away at the Confederate attackers. The artillery, coupled with a Union counterattack, proves too much for Bragg’s men. Bragg withdraws the following day, allowing the Union to claim victory.

12,906

11,739

Bragg gives up the field on January 3 and withdraws his forces southward to Tullahoma. The North is in control of central Tennessee, and the Union victory provides a much-needed morale boost, especially after the recent loss at Fredericksburg in December 1862. But the Battle of Stones River results in some of the highest casualty rates of the war. With only about 76,400 men engaged, it has the greatest percentage of casualties (3.8 percent killed, 19.8 percent wounded, and 7.9 percent missing/captured) of any major battle in the Civil War, even more than at Shiloh and Antietam earlier that year. Four brigadier generals are killed or mortally wounded. Also among the wounded is Union soldier Frances Elizabeth Quinn, who disguised herself to fight as a man. President Lincoln later wrote to Rosecrans, “…you gave us a hard victory which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.”

A pastor who cared for the wounded instead of carrying a rifle, John M. Whitehead, assigned to the Fifteenth Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, received the nation’s highest military honor for the bravery and compassion he showed under fire at the Battle of Stones River.

Whitehead dressed wounds, prayed over the dead and dying, and heard last words. “Of my own regiment every alternate man was either killed or wounded,” Whitehead wrote. “Though a non-combatant, I was with my regiment during the entire battle, comforting the dying, carrying off the wounded and caring for them.” He recalled several of the casualties he saw at Stones River:

Whitehead was 39 years old when the war began and had been ordained as a Baptist minister nearly 20 years before. He continued his ministry with the Baptist church after the war. In the late 1880s, he made his way to Kansas, ultimately moving to Topeka, where he helped build the First Baptist Church. Whitehead’s Medal of Honor for extraordinary heroism was awarded on April 4, 1898. He died in 1909.

Frances Elizabeth Quinn adopted the name B. Frank Miller, disguised herself as a man, and enlisted in the Union army. Passionate about the Union cause, she joined up several times and in several different regiments throughout the war, serving a total of 18 months in infantry and calvary units. Her masculine features made her deception convincing, but each time her true sex was eventually discovered, and she was discharged. At the Battle of Stones River, her identity became known only after she was shot in the shoulder. She was among several women who fought as men in the Civil War.

Quinn’s parents had immigrated from Ireland to La Moille, Illinois, when she was three years old. Both died when she and her brother were young, leaving the children in the care of two separate families. Frances became a surrogate daughter to the Reno family, while Thomas lived with the Cokeley family. When Quinn was 12, she was sent off to be educated at a convent in Virginia. On returning to La Moille, she learned that her brother had run away to join the war at the age of 14. Despite being only 16 and female, Quinn decided to fight too.

On one of the occasions when “he” was revealed to be a “she,” Quinn, using the name Ella Reno, was brought to the attention of Union Gen. Burnside. He didn’t want a female soldier in his army, but he was impressed by her bravery. Burnside put her in the care of an officer’s wife. Soon she had a dress and a hospital job—but she really wanted to get back in the fight. She finally appealed to President Abraham Lincoln, begging him to allow her to remain in service.

Quinn could not stay off the battlefield. In October 1863, under the name Frank Miller, she was captured by Confederates in Alabama and marched to a prison camp in Atlanta, Georgia. Wounded after a botched escape attempt, she was identified as a woman and sent to the hospital. She was released to the Union army in a prisoner exchange on February 17, 1864.

After the war, Quinn moved to Ohio and married Mathew Angel, a soldier from the Second Ohio Heavy Artillery. They had two daughters, but Quinn didn’t live to see them grow up. Only in her mid-twenties, she died on an illness on June 8, 1872.

Stones River: Featured Resources

All battles of the Stones River Campaign

Related Battles

41,400

35,000

12,906

11,739