The Battle of Stones River (known as Murfreesboro to the Confederates) stands as Rosecrans’s first battle in command of the Army of the Cumberland. It was also that army’s first engagement as a complete entity, after fighting piecemeal at Shiloh and Perryville the previous spring and fall. The battle ended as a near-run Union victory, albeit one that tested the Army of the Cumberland more sorely than any other large Federal army had been up to that time. Rosecrans’s army won the battle through quality leadership and hard fighting.

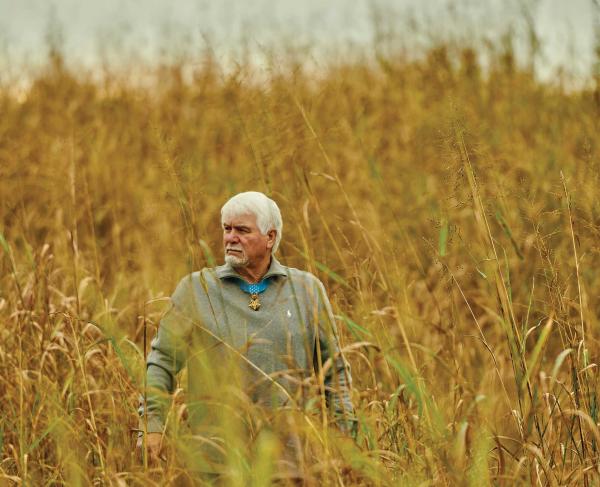

The Army of the Cumberland embarked on this rare winter campaign during the final days of 1862 with some 46,000 of its 70,000 men and a rising star as its commander. An Ohio native and member of the West Point class of 1842, Rosecrans had arrived to assume command on November 1, 1862. For the next seven weeks his army (known officially as XIV Corps, informally as the Army of the Cumberland) refitted in Nashville and prepared for a movement southeast toward Murfreesboro. Gregarious and personable, Rosecrans established himself as a visible and active leader during this period.

Rosecrans divided his force into three corps-sized elements called wings. Command of the Right Wing went to Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook of Ohio, one of Rosecrans’s most experienced subordinates. McCook’s force contained three divisions under Brig. Gens. Jefferson C. Davis, Richard W. Johnson and Philip Sheridan. Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden of Kentucky led Rosecrans’s Left Wing, comprised of three divisions led by Brig. Gens. John M. Palmer, Horatio Van Cleve and Thomas J. Wood. The Center Wing belonged to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, a Virginian who had remained loyal to the Union in 1861. Two divisions under Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau and Brig. Gen. James S. Negley participated in the campaign, while the balance of Thomas’s troops stayed behind to garrison Nashville and its environs. The army moved out from Nashville on December 26 on several parallel roads, trying to snare Bragg’s Confederates, who were camped in an arc south and southeast of the city.

After several days of maneuvering in rain and sleet, dusk on December 30 found the armies facing each other in roughly parallel north-south lines about three miles west of Murfreesboro. Bragg’s men stood in two lines, with Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps (containing the divisions of Maj. Gens. John C. Breckinridge and Patrick R. Cleburne) posted on the right, shielding the city. Across Stones River, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk arrayed his two divisions, with Maj. Gen. Jones M. Withers’s troops in the front line, supported by Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham’s all-Tennessee division. Maj. Gen. John P. McCown’s division anchored the Confederate left. The Federals deployed opposite Bragg in a four-mile line from McFadden’s Ford on the river to the Franklin Pike. McCook held the right, with the divisions of Johnson, Davis and Sheridan in line from south to north. Thomas was posted in the center, with Negley’s division in the front line and Rousseau in reserve. Crittenden straddled the army’s lifeline — the Nashville Pike and the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad — with Palmer’s, Wood’s, and Van Cleve’s divisions. Stones River itself anchored the Federal left flank.

Rosecrans decided to strike on December 31, with the Left and Center Wings attacking astride Stones River and the Nashville Pike toward Murfreesboro. The river crossing was to begin about 7:00 a.m., with the main attack scheduled for an hour later. For the plan to work, McCook needed to hold the Federal right flank for at least three hours. “I trusted General McCook’s ability as to position, as much as I knew I could his courage and loyalty,” Rosecrans admitted later. “It was a mistake.”

Meanwhile, Bragg also planned an attack of his own for the last day of 1862, ordering Hardee to take Cleburne’s division to the left and advance in conjunction with McCown’s division at first light. “The attack [was then] to be taken up by Lieutenant General Polk’s command in succession to the right flank, the move to be made to a constant wheel to the right, on Polk’s right flank as a pivot, the object being to force the enemy back on Stone’s River, and ... cut him off from his base of operations and supplies by the Nashville pike,” Bragg wrote. Bragg sought to fold Rosecrans’s line in on itself like a closing jackknife.

That night Cleburne’s men marched across the Confederate rear, deploying behind McCown’s command shortly after midnight. At 5:45 a.m. on December 31, Hardee made one final check to ensure everything was ready. Shortly after 6:00 a.m., McCown’s officers signaled the advance.

McCook’s right was held by the three brigades of Richard Johnson’s division posted along the Franklin Pike and the Gresham Lane. The men were just awakening and not ready for battle. An Indianan described the scene as McCown’s men struck at 6:25: “Bull Run! You all know what it means. Now, McCook’s corps had a second and improved edition ... Confusion arose, a terrible panic gripped the troops.”

Johnson’s units disintegrated under the weight of the sudden attack, reeling north and losing more than 2,000 men taken prisoner. Cleburne’s division swung into action against Davis’s division, which was posted in a cedar thicket. The Federals stood for 30 minutes, until McCown attacked Davis’s open flank. “The right of the division was completely crushed in,” recalled the commander of the 5th Kentucky (U.S.). The Federals fled north; in 90 minutes the Confederate attack had shattered two of McCook’s three divisions.

Along the Nashville Pike, Rosecrans and his staff heard the firing on the right, but thought little of it. Crittenden’s crossing at McFadden’s Ford began as planned at 7:00 a.m. Thirty minutes later, a staff officer from McCook reported vaguely that “the right wing was heavily pressed and needed reinforcements,” to which Rosecrans replied, “Tell him to dispose his troops to best advantage and to hold his ground obstinately.”

Shortly thereafter, when another of McCook’s staffers gave a clearer picture of the Right Wing’s disaster, Rosecrans immediately recalled his men back across the river and cancelled the offensive. One brigade stayed behind to guard the crossing, while the balance of Van Cleve’s division and the divisions of Wood and Rousseau marched to the sound of the guns. Now determined to save the army from destruction, General Rosecrans and his staff rode to the front.

Meanwhile, the fighting had spread, as Withers’s and Cheatham’s Confederates attacked Sheridan’s prepared division about 7:30 a.m. “The enemy ... attacked me, advancing across an old cotton-field ... in heavy masses,” recalled Sheridan. The Federals held on in see-saw fighting. The collapse of Davis’s division opened Sheridan’s flank and rear, forcing his men to retreat under assault from three sides. Sheridan slowly retired the division north of the Wilkinson Turnpike, joining with Negley’s men in a large patch of cedars and rock outcroppings. Lt. Arthur MacArthur of the 24th Wisconsin summed up the action in a letter home: “At length we arrived in the woods, and here was a general retreat, and I would not have given a snap of my fingers for the whole army.” At this critical moment, Federal reinforcements arrived.

As Sheridan took up his new position, Rousseau deployed his infantry in the cedars to Sheridan’s right. Col. John Beatty’s brigade led the march into “a cedar thicket so dense as to render it impossible to see the length of a regiment.” “Here the struggle of the day took place,” recalled Col. Robert B. Vance of the 29th North Carolina. “The enemy, sheltering themselves behind the trunks of the thickly standing trees and the large rocks, of which there were many, stubbornly contested the ground inch by inch.” The Confederates fell back under the weight of Federal fire.

While Rousseau’s men fought in the cedars, the divisions of Sheridan and Negley struggled to hold their position. Because of the V-shape of their line, Confederate attacks converged on the wooded rocky outcroppings along the Wilkinson Pike. The Federals sheltered in the woods and rocks, while the Confederates approached across several hundred yards of open cotton field. As the action began, Rosecrans ordered Negley and Sheridan to defend the position to the last extremity. “Every energy was therefore bent to the simple holding of our ground,” recalled Sheridan.

For an hour the Confederates hammered this area with concentrated artillery fire and repeated infantry charges, earning the area the moniker “the Slaughter Pen.” The Union troops held on, repulsing all attacks, as the fighting settled into a bloody stalemate.

To Sheridan’s right, Rousseau’s men were less successful in standing against increasing Confederate pressure. Most of Rousseau’s units fell back, but John Beatty’s brigade held firm until, realizing its growing isolation, the troops fell back to the pike. The Confederate pursuit turned the retreat from the cedars into a rout. “The field [between the cedars and the Nashville Pike] is by this time covered with flying troops, and the enemy’s fire is most deadly,” remembered Beatty. Rousseau rallied his men along the road near a cannon-studded knoll that dominated the area.

Rousseau’s retirement allowed the Confederates to threaten the divisions of Sheridan and Negley with encirclement, and both generals now directed their men rearward. To an observer it looked like “ten thousand fugitives ... burst from the cedar thickets and rushed into the open space between them and the turnpike.” The divisions rallied along the Nashville Pike.

As the battle among the cedars ended about 11:00 a.m., the battle hung in the balance, as fighting shifted to the area along the Nashville Pike. In this crisis, leadership made the difference between victory and defeat. In contrast to the passive Bragg, who preferred to remain in the rear, Rosecrans and his staff dashed around the battlefield giving advice, orders and encouragement to the troops — often under fire. Scores of Federals wrote of seeing the commanding general on his gray horse, an unlit cigar clamped between his teeth. Rosecrans’s presence at the front heartened his army; as one officer later wrote: “I could not help expressing my gratitude to Providence for having given us a man who was equal to the occasion — a general in fact as well as in name.” Division commander Palmer later said, “If I was to fight a battle for the dominion of the universe, I would give Rosecrans the command of as many men as he could see and who could see him.” Rosecrans also took time to visit McFadden’s Ford, where Col. Samuel Price’s small brigade guarded the key crossing. “Will you hold this ford?” he queried Price. “I will try, sir,” was the reply. “Will you hold this ford?” Rosecrans asked with more emphasis. “I will die right here,” affirmed Price. “Will you hold this ford?” the general demanded again. “Yes, sir,” came the answer. “That will do,” replied Rosecrans, who rode off.

Now the commanding general again led from the front. After helping rally Rousseau’s men, Rosecrans put his Pioneer Brigade into line and personally directed Van Cleve’s men into position on the far right. The first Confederates now hit the Union line. “They came on like demons,” recalled a Regular. The 18 cannon on the knoll anchored the Federal defense. The shelling made “gap after gap in [the Confederate] ranks. The fire was rather too hot to suit them and what few of them was left came to an about face and skedaddled back to the cedar woods for shelter,” recalled an observer. During this action other Confederate attacks battered Palmer’s division astride the pike, forcing it to give ground.

Rosecrans realized his army needed a respite to coalesce its new line along the pike, time he decided to buy at the expense of the army’s Regular Brigade. General Thomas passed the order to the brigade commander, Lt. Col. Oliver L. Shepherd: “Shepherd, take your brigade in there and stop the Rebels.” The 1,400 professional soldiers of the 15th, 16th, 18th and 19th U.S. Infantry Regiments marched out to Negley’s former position. There, they collided head on with a Confederate advance; after a short but sharp fight the Regulars retired, leaving 44 percent of their number behind as casualties. Despite the horrific loss, their sacrifice slowed the Confederate momentum and enabled the Army of the Cumberland to settle in along the Nashville Pike.

As the last afternoon of 1862 began, Bragg’s troops moved to break this new line and win the day. McCown’s tired division attacked the knoll again. Generals Rosecrans and Rousseau personally led the defense. “The enemy’s lines, with banners flying, came in sight on the verge of the timber, within 500 yards of our battery,” recalled Lt. Alanson J. Stevens of Battery B, Pennsylvania Light Artillery. “We opened on them with spherical case, shell, and canister.” The intense fire proved too much, and the Confederates retreated back into the woods. The Federal center was safe.

The next crisis developed on the Federal right, as Cleburne’s division thrust north toward the Nashville Pike. His men collided with Van Cleve’s division, forcing it back after 20 minutes of close-quarter combat. As Cleburne’s victorious skirmishers reached the pike, Van Cleve launched a countercharge led by the 13th Michigan, 13th Ohio and the 59th Ohio. Surprised by this sudden surge, Cleburne’s exhausted infantry faltered and fell back. Hardee called a halt at 3:00 p.m., after eight hours of marching and fighting. “It would have been folly, not valor, to assail them in this position,” he explained. The Confederates stopped mere yards short of their objective; the Federal right had bent but not broken.

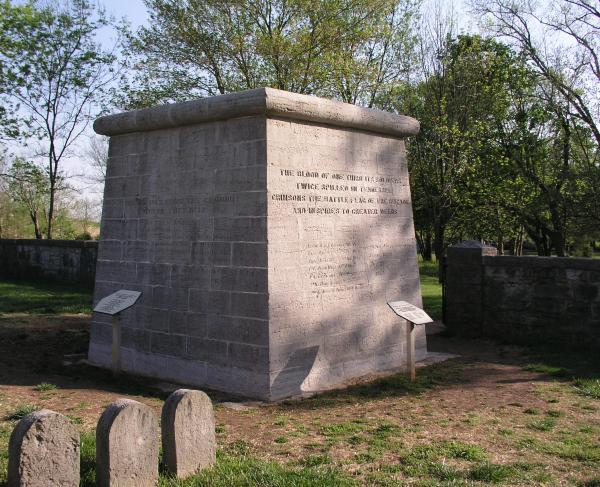

The battle’s focus now shifted to the Federal left, the only part of the line still in its original location from daybreak. The defense was centered at a four-acre circular cedar brake known to both sides as the Round Forest. The wood itself stood on a slight elevation, forcing the Confederates to approach it along flat cotton fields running 700 yards eastward. If the Round Forest fell, the entire Federal position would collapse. A brigade under Col. William B. Hazen held the Round Forest itself, supported by the brigades of Brig. Gen. Milo Hascall and Col. George D. Wagner and elements of other divisions.

Over in the Confederate lines, Bragg had ordered Breckinridge to send most of his division across Stones River to support the main battle. The first two of Breckinridge’s brigades, under Brig. Gens. Daniel W. Adams and John K. Jackson, arrived about 1:30 p.m. Lt. Gen. Polk committed them, as he later explained, “To drive in the enemy’s left and especially, to dislodge him from his position in the Round Forest. Unfortunately, the opportune moment for putting in these detachments had passed.” Nonetheless, Polk decided to make the assault.

Polk compounded his error by throwing his men forward as quickly as they deployed. Adams’s Louisiana and Alabama command led the charge at 2:30 p.m., with flags flying. The defenders greeted Adams’s Confederates with a “terrible fire,” according to an officer. “Finding that I was overpowered in numbers ... I had reluctantly to give the order to fall back,” said Adams. The Confederates fled the field in disorder, having tried to do what General Adams called “more than any brigade could accomplish, and full work for a division, well directed.” Jackson’s men soon suffered the same fate.

“A period of about one hour now ensued with but little infantry firing, but a murderous shower of shot and shell was rained from several directions upon this position,” recalled Hazen. Rosecrans toured the line with General Hascall, encouraging the men. Meanwhile, Breckinridge reported in with two more brigades, which Polk ordered to form for a mass attack against the Round Forest.

“At about 4:00 p.m. the enemy again advanced upon my front in two lines,” recalled Hazen. “The battle had hushed, and the dreadful splendor of this advance can only be conceived, as all description must fall vastly short.” Federal artillery and infantry fire tore into the massed Confederates, making a noise so intense that men from both sides picked cotton from the field to plug their ears against the din.

Rosecrans watched the action from the knoll and spurred his horse toward the Round Forest while a shell decapitated the Army of the Cumberland’s chief of staff, Lt. Col. Julius P. Garesché. As Rosecrans arrived on the scene, Breckinridge’s Confederates fell back and the final dusk of 1862 ended the fighting.

That night Rosecrans called a meeting of his commanders, although it produced no consensus on whether to stand or withdraw. Thomas declared, “This army does not retreat.” Rosecrans agreed, ordering his generals to “Go to your commands and prepare to fight and die here.” He consolidated the Army of the Cumberland’s position, and ordered his men to fortify their lines.

New Year’s Day 1863 dawned cold and rainy, as both sides skirmished without attempting a major attack. In the afternoon Van Cleve’s division (now led by Col. Samuel Beatty, Van Cleve having been wounded the previous afternoon) crossed Stones River and occupied a wooded ridge overlooking Polk’s lines.

The dreary weather continued on January 2, as Bragg realized that Samuel Beatty’s troops on the ridge held a key advantage and decided to send Breckinridge’s division back across the river to recapture the position.

At 4:00 p.m., Breckinridge commenced the attack. The Confederates struck hard at Beatty’s two frontline brigades, under Cols. Price and James P. Fyffe. The Federals spilled “backwards like fall leaves before a wintry wind; one after another the lines were swept away,” wrote Fyffe. After 20 minutes of fighting, Breckinridge’s division had achieved its objective.

The Confederates next chased the Federals down the ridge’s rear slope into an open area opposite McFadden’s Ford. Maj. Gen. Crittenden turned to Capt. John Mendenhall, the Left Wing’s chief of artillery. “Now, Mendenhall, you must cover my men with your cannon,” he said. The captain lined 57 guns on a bluff overlooking the ford and opened a concentrated bombardment on the Confederates that shook the ground. Federal infantry reinforcements arrived in the form of Negley’s division, the Pioneer Brigade, and two brigades under Hazen and Cruft; Negley signaled an immediate counterattack into the failing light. “From a rapid advance, [the enemy] broke at once into a rapid retreat,” wrote Crittenden. A soldier in the 41st Ohio of Hazen’s brigade wrote, “Breckinridge’s scattered men ... made little show of resistance, but took themselves off.” The Federals regained all of the lost ground, capturing three Confederate cannon. Nightfall ended the fighting. In less than one hour, Breckinridge’s division had sustained 1,400 casualties.

This fighting ended the Battle of Stones River, the Civil War’s bloodiest battle by percentage of loss. In three days of fighting, Rosecrans lost 13,249 men killed, wounded, missing or captured of 46,000 men, a 28 percent loss rate. Bragg’s army engaged 37,000 and sustained 27 percent casualties, or 10,266 men.

On January 3 reinforcements and supplies from Nashville arrived. That night Bragg retreated, and the Federals occupied Murfreesboro on January 5. A justifiably proud Rosecrans telegraphed to the War Department in Washington: “God has crowned our arms with victory. Our enemy are badly beaten, and in full retreat.” Exhausted and facing worsening weather, the Federals went into winter quarters. On January 8, the army officially received the designation Army of the Cumberland.

Rosecrans’s victory buoyed Union spirits at a critical time, just as the war’s aims changed and emancipation took effect on January 1, 1863. Stones River also helped reduce the sting of battlefield failures in Virginia and Mississippi during the previous month. President Lincoln himself attested to the victory’s impact when he wrote to Rosecrans in August 1863: “I can never forget, whilst I remember anything, that about the end of last year, and the beginning of this, you gave us a hard earned victory which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.”

At Stones River, the Army of the Cumberland had been battered and pushed to the brink of annihilation like no other large Federal field army had in the war so far, but it emerged victorious through a combination of hard fighting and superb leadership. The steady examples of leaders like Rosecrans, Thomas, Crittenden, Sheridan, Rousseau, Negley, Van Cleve, Hazen and others helped hold the army together through a near-death experience. As one veteran summed up, the Federal army and its leadership at Stones River had “plucked victory from defeat and glory from disaster.”

Learn More: Battle of Stones River