Fredericksburg

What do Henry Adams, Louisa May Alcott, Clara Barton, Ambrose E. Burnside, Jefferson Davis, Frederick Douglass, William Gladstone, Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, Abraham Lincoln, Karl Marx, Napoleon III, Horatio Seymour, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Walt Whitman all have in common? The simple answer is that all of them were somehow connected to the Battle of Fredericksburg. More broadly speaking, the list of names itself – by no means complete – suggests how the battle and its effects reverberated, not only in the United States but across the western world.

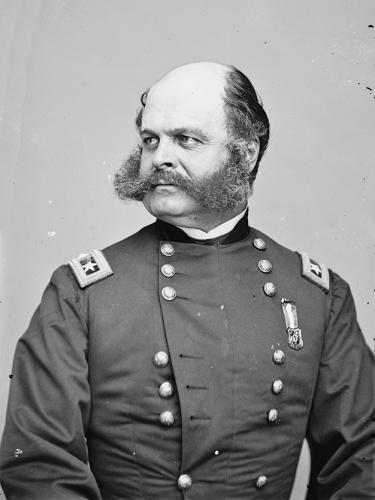

Among students of the Civil War, however, Fredericksburg has long been neglected. Think of how much more attention has been paid to Antietam fought a couple months earlier or Chancellorsville fought a few months later. There are some explanations. For one thing Fredericksburg was a Confederate victory but a Union story. On the Confederate side, Fredericksburg seemed too easy a victory, or as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson certainly believed, an empty victory. Therefore few historians interested in the Army of Northern Virginia have considered Fredericksburg worthy of extensive study. Nor have there been any significant controversies about Confederate strategy or tactics at Fredericksburg. On the Union side of the ledger, Fredericksburg has generally been seen as just one more blunder in a series of Federal blunders in the Eastern Theater beginning on the Virginia Peninsula and concluding at Chancellorsville. All the strategic and tactical debates have dealt with the Union conduct of the campaign and battle. It is all too easy, and simple-minded, to pillory Ambrose E. Burnside and stop there, concluding that Fredericksburg carries little interest for military historians or any larger significance for the course of the war. To anyone interested in the Army of the Potomac, it has often seemed that the Battle of Fredericksburg produced horrific bloodletting and little else.

In some ways Fredericksburg was a deceptive signpost in the war – a misleading high point for the Confederates and a misleading low point for the Federals – yet this very quality makes the campaign worthy of more extended examination. Fredericksburg took place during a nadir in Union fortunes. In October and November, Democrats had made significant gains in state and federal elections, most notably electing Horatio Seymour governor of New York. Shortly after these defeats – which many blamed on the lack of progress in the war – Lincoln finally replaced the cautious and slow-moving George B. McClellan with Ambrose E. Burnside. Burnside repeatedly said he was not up to the job but reluctantly accepted it. He inherited an army filled with McClellan loyalists and the scheming Joseph Hooker who thought he should have received the appointment. Burnside had no real political enemies but significantly he had no staunch political allies, and there would be no one in Washington standing by him if things went sour.

His first mistake was to reorganize the army into three grand divisions of two corps each (commanded by William B. Franklin, Joseph Hooker, and Edwin V. Sumner). This organizational scheme made a certain amount of sense but not at the start of a campaign with a new man commanding the army, and it proved cumbersome and inefficient during the battle. Burnside’s second major decision was to advance on Richmond by way of Fredericksburg. The first Federals arrived at Falmouth on November 17, but the expected bridging materials for the pontoons needed to cross the Rappahannock River would not arrive for ten more days. At this point Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia could not be sure of Burnside’s intended crossing point, but they were coming to the close of a most successful season of campaigning and exuded confidence.

From the outset, Burnside’s decisions would generate enormous controversy. Should he have taken Sumner’s advice and crossed before the pontoons arrived? Perhaps, but had he done so, Lee planned to withdraw his forces to what he considered a much more defensible position along the North Anna River. Should Burnside have followed the recommendations of Hooker and others to have crossed upstream or downstream? Maybe, but he ultimately decided to move his army directly into Fredericksburg where Lee would least expect an attack. Timing proved equally troublesome as Burnside came under increasing political pressure. Northern newspapers were carrying their usual “On to Richmond” headlines. More ominously, Burnside would begin the battle without the support of his subordinates and without fully explaining his plans to anyone.

All these problems bore immediate and poisonous fruit in the conduct of the battle itself. On December 11, pontoons were successfully built below Fredericksburg, but Union engineers trying to lay bridges going into town faced stiff resistance from William Barksdale’s Mississippians. In utter exasperation, Burnside ordered the town shelled. Union infantry finally forced themselves across the Rappahannock in boats, and the pontoons were finally completed. The war’s conduct seemed to be taking a turn for the worse. Sharp and deadly street fighting – highly unusual during this war – was followed by a thorough Union sack of the town that continued during and after the battle. Soldiers entered the homes of rich and poor alike stealing all kinds of items and generally vandalizing the place. Some men even donned women’s dresses to mock the aristocratic pretensions of “secesh females” in a kind of street theater.

While the Federals frolicked in the streets, Lee took advantage of the delay to bring Jackson’s corps into position. Should Burnside have crossed more of his troops on December 11 and have attacked on December 12 before Lee could reunite his divided army? Some contemporary observers and later historians have concluded that this in fact proved to be Burnside’s greatest blunder.

On December 13, ambiguous orders and general confusion caused still more delays. Although Burnside hoped to attack the Confederate right and divide Lee’s army in two, there was little understanding among the high command about the details or the timing. On the Union left, muddy ground, poor roads, woods and gently rising Prospect Hill favored the defenders, but an unprotected gap in Jackson’s lines allowed George G. Meade’s division to cross the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac railroad. Yet Meade’s attack was only weakly supported and his men along with John Gibbon’s division were repulsed by a furious Confederate counterattack. The fighting raged furiously over what soon became known as the “Slaughter Pen,” vitally important ground that now offers an almost matchless preservation opportunity. The cautious Franklin commanding the Left Grand Division proved slow in funneling more men into the fight.

Early reports of success on the Union left, however, led Burnside to assume that Lee might have weakened the Confederate left and so he ordered brigades from Sumner’s Right Grand Division to move out of Fredericksburg and assault the Confederate lines. These troops would emerge from town and cross a millrace – still 500 yards from the Confederate positions on Marye’s Heights. From there only a slight swale offered advancing soldiers any cover. Georgians and North Carolinians were stationed behind a four-foot high stone wall along a sunken road at the base of Marye’s Heights. Lee and Longstreet had carefully prepared their defensive positions, and even before the Federals had left the comparative safety of the town, they would come under heavy artillery fire, and as they approached the stone wall, they would run into what many described as a sheet of flame as the Rebel infantry rose and fired. Successive attacks – some head on, others trying to flank the stone wall – left regiments and entire brigades shattered.

As much as any other Civil War battle, Fredericksburg raised difficult question about how the officers and their men could keep assaulting such a seemingly impregnable position. What explains their valor? Many but by no means all were combat veterans trained to obey orders and stick by their comrades.

Others felt caught between duty and fear and so moved forward with their company. In any case the losses were staggering and kept mounting through the day. Hooker opposed pouring his troops into the attack, but there were inaccurate reports that Confederate artillery was being withdrawn and that some Federals had reached Marye’s Heights, and so Burnside decided to press the attacks. By nightfall, seventeen Union brigades had attempted to attack the Confederate left – hundreds of men lay trapped on the field “80 paces from the crest and holding on like hell” reported one Union general – amidst the screams of the dying and wounded.

Even then Burnside had to be talked out of launching additional attacks on the morning of December 14. By December 16, the Union forces had skillfully slipped back across the Rappahannock. As for the Confederates, Lee had fully expected Burnside to renew the assaults and was greatly frustrated by what he considered an incomplete victory.

Yet the story of Fredericksburg carries a much broader significance than this bare sketch of the strategy and tactics can convey. From the soldiers’ perspective, and especially for the Federals, a winter campaign had seemed foolish from the outset. Many men in both armies worried that exposure and disease would take a heavier toll than enemy bullets. Hard marching and a sharp cold snap in early December had all affected the bluecoats’ expectations and their morale. Rumors about possible command changes had swirled through the camps along the Rappahannock; of course such speculation only intensified in the aftermath of Fredericksburg.

The Federals had sacked the town and the Confederates had stripped the dead, and so it seemed the war itself threatened to spin out of human control. Burial truces – along with the sights, sounds, and smells of the dead – had all driven home the rising costs of civil war. Surgery by candlelight on the evening of December 13 epitomized these horrors for some soldiers. Visiting his slightly wounded brother George, Walt Whitman noticed a “heap of amputated, feet, legs, arms and hands” near one hospital tent. Clara Barton vividly described the treatment of the wounded at Chatham Manor just on the other side of the Rappahannock River. Eventually these sufferers would be taken to division hospitals or transported to Washington where Louisa May Alcott and others worked.

The sheer numbers were staggering: 12,653 Union casualties (1,284 dead) and 5,309 Confederate casualties (595 dead). The perceived casualties as reported in both Union and Confederate accounts ran to 20,000 on the Union side, making the defeat and its costs seem even worse. Long lists of the dead and wounded soon appeared in newspapers. Confederates in particular offered memorable descriptions of the dead piled high, and Americans in general struggled to find meaning in the carnage. The pious might simply look to divine providence, and by this point in the war, heartfelt eulogies for Christian soldiers had become commonplace. As for the families, they often had to settle for unreliable newspaper reports or long-delayed word from a commanding officer, chaplain, or a hospital steward reporting on their loved one’s fate.

In fact news from the battlefield carried enormous importance to everyone from a poor private’s wife to the President of the United States. The telegraph slips in the Abraham Lincoln papers at the Library of Congress tell us precisely what the President knew and when he knew it. The initial dispatches had contained encouraging reports, soon followed by more ambivalent ones. Finally a reporter from the New York Tribune called on Lincoln to describe the full dimensions of the disaster. In modern parlance, newspapers immediately went into “spin” mode. Republicans editors tried to be more optimistic while Democratic papers quickly reported another crushing Union defeat. Bad news reverberated abroad. Working for his father the American minister to Great Britain, Henry Adams wrote of “screwing his courage up to face the list of killed and wounded.” The Times of London talked of the impending fall of the American republic. Well might William Gladstone or Napoleon III for that matter wonder if the United States could survive and if the Confederates had in fact established themselves as an independent nation. Even Karl Marx wrote in detail about Burnside’s failure.

The Battle of Fredericksburg carried consequences large and small, expected and unexpected. The defeat helped spark a political crisis in which Republican senators nearly succeeded in driving Secretary of State William H. Seward from the cabinet. The rising price of gold in New York – which one banking magazine explicitly linked to Fredericksburg – further deepened the gloom in Washington and across the North. Abolitionists, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, worried that this latest Union defeat might cause Lincoln to delay issuing the final Emancipation Proclamation.

Recrimination became the order of the day. Who was to blame? Burnside? Halleck? Lincoln? The soldiers themselves bandied about words such as “slaughter” and “butchery” to describe the battle; there were loud calls for McClellan’s return to command. Burnside took full responsibility though Lincoln issued a bizarre letter suggesting that the failure was mostly “an accident” and congratulating the army that the casualties had been “comparatively so small.”

Yet the Army of the Potomac survived to fight another day – in fact survived the disastrous Mud March and another crushing defeat at Chancellorsville. We often think of soldiers in the twentieth or twenty-first centuries as men more likely to fight for their buddies than for any idealized cause, but the fighting men of the 1860s unblushingly spoke of patriotic duty. In doing so, they embraced no vague abstraction; for them patriotism always had some tangible meaning. Shortly after McClellan’s removal from command, a member of the 6th Wisconsin had clearly explained the proper response to such a controversial decision: “The American soldier is true to his country, true to his oath, and resolved to fight the rebellion to the bitter end no difference who commands. [I] am not a McClellan man, a Burnside man, a Hooker man, i am for the man that leads us to fight the Rebs on any terms he can get.”

Civilians might not understand this way of thinking though many soldiers admitted that the combat at Fredericksburg defied their powers of description. In any case, the men often had little respect for civilian opinion. One Federal described stay-at-home critics of the Army of the Potomac as “men who have not spunk enough to leave their mammy long enough, let alone to the face the enemy.” These were “men who are setting on their asses by warm fires and enjoying all the comforts of home, running down men who are enduring hardships all the time and risking their lives to restore their country.”

If it was easy to blame the generals or the politicians for the defeat, most Federals were convinced that the soldiers themselves had fought with remarkable courage. As one private explained, “We were defeated because bravery and human endurance were unequal to the undertaking.” Brave charges against strong positions increasingly seemed like nothing so much as madness if not murder, but soldiers still talked of courage and honor – virtues to which everyone could aspire. A captain in the Irish Brigade expressed this ethos best: “even the humblest private may be styled a hero.”

At the same time the demoralization and defeatism in the army in the wake of Fredericksburg was undeniable. After witnessing horrific bloodshed during the battle on December 13 and after having been pinned down by Confederate sharpshooter fire on December 14, a Minnesota volunteer ruefully commented, “I lost a chunk of my Patriotism as large as my foot.” “Nothing gained” became one of the most common and most depressing phrases in post-battle letters home. The camps around Falmouth reminded men of Valley Forge and soldiers became obsessed with simply staying warm and worrying about their next meal. “The boys are most crasey for fear we shall have to giv thoes rebs another hack,” a New Hampshire soldier wrote home, “but that is the least that troubles me as long as I can get enough to eat.” Advising his brother to “steer clear” of the army, a member of the famous Iron Brigade added that “a good soldier cares more for a good meal than he does for all the glory he can put in a bushel basket.”

But despite all the grousing and a rising tide of desertions, another quality was apparent in the soldiers – perseverance. This might involve a minimalist standard of courage as described by a Pennsylvania chaplain: “Our battle-worn veterans go into danger when ordered, remain as a stern duty so long as directed, and leave as honor and duty allow.” Drawings of officers leading charges that appeared in the illustrated newspapers elicited derisive howls of laughter in camp. Some soldiers swore they would never enter a battle again. Although many of these men would still do their duty, for several weeks after Fredericksburg such statements also reflected a deep despondency about the Union cause.

Yet in addition to perseverance, Union soldiers also demonstrated a remarkable resilience. One lieutenant admitted that some of the men might have been “cursing the stars and stripes” right after the battle, but “these same soldiers will fight like bull dogs when it comes to scratch.” Indeed the grumbling veterans could be “relied upon more.” The quickest way to end the war, this soldier believed, was to give the Rebs a good whipping and silence the “croakers” at home.

Indeed, memories of sacrifices already made and comrades lost sparked a kind of patriotic revival among Burnside’s men, not the flag-waving and hurrahing variety but rather the quiet kind of resolve that carried armies to victory. Disillusionment and despair would not necessarily tear most men away from a still firm commitment to finishing their work. A Pennsylvania captain admitted being tempted to let others do the fighting but could never quite bring himself to act on this impulse. “I am a soldier and a good one,” he noted with unaffected pride. He would “growl” after a fight but when “an order came to storm a battery, nary a squeal would I make.” This last statement made up for the bad food, the damp ground, and the harsh talk about Burnside or Lincoln. It overshadowed the swearing, the grumbling, and wild talk of mutiny. It perhaps counted for more than demoralization and even desertions.

War demanded a great deal of soldiers and pushed them to the breaking point and beyond, but armies somehow managed to survive the worst. Even among fellows who cursed incompetent officers and railed against cowardly civilians, there remained a spark, hopeful if not exactly optimistic. These soldiers often despaired of their own government but not of their comrades – men who had stood the fire before and who would not shrink from it next time. Corporal Peter Welsh of the Irish Brigade in a long letter explaining to his wife why he stayed in the ranks recaptured this spirit of hard-headed yet still idealistic patriotism. “This is my country as much as the man that was born on the soil and so it is with every man who comes to this country and becomes a citizen.” Even a war filled with “errors and mismanagement” carried a “vital interest” for “people of all nations.” Anticipating Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Welsh defined the stakes: “This is the first test of a modern free government in the act of sustaining itself against internal enemys and matured rebellion all men who love free government and equal laws are watching this crisis to see if a republic can sustain itself in such a case if it fails then the hopes of millions fall and the designs and wishes of all tyrants will suceed the old cry will be sent forth from the aristocrats of europe that such is the common end of all republics the blatant croakers of the devine right of kings will shout forth their joy . . . . it becomes the duty of every one no matter what his position to do all in his power to sustain for the present and to perpetuate for the benefit [of] future generations a government and a national asylum which is superior to any the world has yet known.” Perhaps better than any other statement from a common soldier, Welsh’s tribute to American democracy explained how the Army of the Potomac would survive to fight another day. It is also such statements that explain why the Battle of Fredericksburg, fought over 140 years ago, holds such fascination and importance for anyone who would attempt to understand the causes, conduct, and consequences of the American Civil War.

George C. Rable is the Charles G. Summersell Chair in Southern History, University of Alabama and currently President of the Society of Civil War Historians. He is the author of Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!, which was award the Lincoln Prize, the Society for Military History Distinguished Book Award in American Military History, the Jefferson Davis Award, and the Douglas Southall Freeman History Award. He is currently writing A Religious History of the American Civil War.

To restore land and history at Gettysburg, Cold Harbor, Slaughter Pen Farm and New Market Heights, we must raise $131,000. Please help to finish the...