The True Battle for Fredericksburg

The winter of 1862 was a troubling time for Abraham Lincoln and the Union army. The president had assured voters that the war was progressing as planned, but the Confederate armies of Generals Robert E. Lee and Braxton Bragg seized the initiative just before the fall elections in the North. Union armies beat them back, but disillusioned Northerners were shaken by the experience. Abraham Lincoln needed a military victory to allay their fears, silence his political critics, and give strength and credence to the Emancipation Proclamation, which he intended to sign on New Year’s Day 1863.

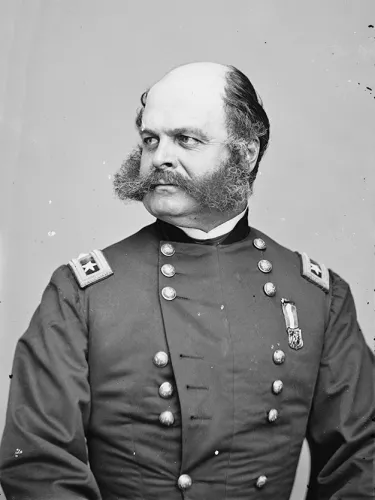

Lincoln’s constant pressure on the latest commander of the Army of the Potomac compelled the affable Major General Ambrose E. Burnside to override all military considerations to accommodate the president – even after his campaign stagnated on the Rappahannock River opposite Fredericksburg, Virginia, in November 1862. The river had blocked his march south, and for two weeks the Union army had no pontoon bridges to cross the stream. Confederate General Robert E. Lee anticipated Burnside’s next move, and marshaled his army around Fredericksburg. Once his pontoons arrived, Burnside resolved to cross the river directly at Fredericksburg, relying on speed and surprise to seize the city and its surrounding hills before the Confederates could react and concentrate their forces.

Northern engineers began building pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River before dawn on December 11, 1862. Unfortunately for Burnside, speed and surprise both collapsed at the river’s edge. Confederate sharpshooters, posted along the riverfront by Brigadier General William Barksdale, blazed away at Burnside’s bridge-builders, and drove them from their work. Union artillery shelled the city without effect. Ultimately, Northern infantry in pontoons ferried across the river under fire to establish a bridgehead and force the Southerners away. Even then, Barksdale’s Mississippians persisted in fighting amid the houses and in the streets. Barksdale delayed Burnside’s army for almost twelve hours, and thoroughly wrecked the Union general’s plans. Lee had ample time to divine Burnside’s intentions and to concentrate his army on the hills outside of Fredericksburg.

Ambrose Burnside examined Lee’s defenses, determined to attack. He concluded that the Confederates occupied eight miles of ridges, marking the western face of the Rappahannock valley. Their line was concave in shape, with the center bowed away from the river and the Union army. Burnside could not attack Lee’s center without getting caught in a crossfire. That left only two alternatives: He had to strike one or the other end of Lee’s defenses, where the lines jutted forward forming two salients. The Union commander decided to strike both. He would launch his main attack south of Fredericksburg against Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Confederate Second Corps at Prospect Hill. His secondary strike would hit Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s Rebels at Marye’s Heights and the stone-lined Sunken Road. Burnside hoped to keep Longstreet occupied, so he would not interfere with the battle against Stonewall Jackson. Visitors to the Fredericksburg Battlefield automatically assume that the waves upon waves of Union attackers hurled against Marye’s Heights formed the principal part of the action at Fredericksburg. The “real” battle occurred some three miles to the south – in an area known as Prospect Hill and the Slaughter Pen. The battle for the Slaughter Pen became, in essence, the true Battle for Fredericksburg.

Union and Confederate armies clashed on the field south of Fredericksburg on December 13, creating one of the most sobering milestones in Civil War history. The Union army arrayed half of its strength – 65,000 men – opposite Stonewall Jackson’s 37,000 Confederates. Unfortunately, Burnside’s orders did not reflect his plans. Ambiguous language confounded Burnside’s chief lieutenant on the left, Major General William B. Franklin. Uncertain of Burnside’s intentions, Franklin committed a bare minimum of troops – and Burnside’s overwhelming drive dwindled to just two divisions (approximately 8,000 attackers). Major General George Gordon Meade would launch the main attack with an understrength division of Pennsylvania Reserves, and Brigadier General John Gibbon’s division would support him.

Union artillery unlimbered in a vast muddy field, soon to be known as the Slaughter Pen. The ground had been part of Arthur Bernard’s Mannsfield plantation, and still had some residual corn and wheat stubble from the last harvest. Guns opened fire at 10 a.m., first engaging Major John Pelham’s lone Confederate gun hovering on the Union left flank. An hour later, Northern guns turned their full might on the hills held by Stonewall Jackson’s veterans. The Rebels refused to respond, provoking Meade and Gibbon to advance at noon. Stonewall Jackson’s artillery suddenly came to life, smothering the attackers with bursting shells and shrapnel. Union soldiers took cover behind a slight ridge, and Union guns answered the Confederate cannon with a vengeance. Union and Confederate soldiers endured an unnerving hour of shellfire. When Union skirmishers withdrew from in front of the cannon, Union private George E. Maynard realized that one of his comrades was missing. Maynard returned to the field, found his wounded friend between the lines, and carried him back to safety. Maynard’s daring earned him the Medal of Honor – the first of five medals awarded for action in the Slaughter Pen.

Meade’s division surged forward again at 1 p.m. Gibbon was surprised by Meade’s sudden advance, and hurried to keep pace. Meade’s Pennsylvania Reserves penetrated a finger of woods that turned out to be a marshy gap in the Confederate front. Meade’s men fought their way into the heart of Stonewall Jackson’s defenses. Gibbon offered support by attacking across an open field with two brigades – one behind the other. Major General Ambrose Powell Hill’s Confederates took cover behind the railroad embankment of the R. F. & P. Railroad. As Gibbon’s first line approached, Rebels ripped it apart with deadly musketry which stopped the Yankees cold. When the first brigade faltered, the second took its place. The second attack also failed, and casualties accumulated at a fearful rate. John Gibbon brought forward his last brigade, and personally led a third assault, which reached the Southern line.

Confederates shot down numerous Union color-bearers, and the attack appeared to lose momentum. Several soldiers stepped forward, seizing the flags, and led the Union thrust toward the railroad. Three men, Philip Petty, Martin Schubert, and Joseph Keene, won the Medal of Honor for their actions during Gibbon’s assault by carrying the colors. Petty rescued the 136th Pennsylvania’s flag when its color-bearer threw away the banner and fled. Martin Schubert had a medical furlough in his pocket, but opted to stay with his regiment. When the 26th New York’s flag was shot down, he carried it forward until he, too, fell wounded. Joseph Keene then picked up the standard and kept the attack moving. Both sides had run out of ammunition by this time, and the battle devolved into a savage hand-to-hand combat. Gibbon’s men captured the railroad, pushing the Confederates into the marsh. Gibbon ordered his men to regroup before pursuing the Confederates into the wetlands.

Jackson’s men quickly rallied, and contained Meade’s breakthrough. The fighting became close and intense, but Confederate numbers ultimately prevailed, driving the Northerners out of their lines at 2:15 p.m. Fifteen minutes later, the Confederates repulsed Gibbon’s advance – and then counterattacked. Gibbon was severely wounded in the wrist by a bursting shell, making him the highest ranking U.S. officer injured in the Battle of Fredericksburg. Caught up in the excitement of the counterattack, the Confederates charged over the railroad and entered the Slaughter Pen. Georgians, Virginians, and North Carolinians swarmed after Meade’s and Gibbon’s men. Union artillery blasted the Rebels with canister, cutting them down in droves. The Northern guns blunted the surge, but Union infantry compelled the Confederates to retreat from the field. Colonel Edmund N. Atkinson was wounded and captured while leading a Georgia brigade into the Slaughter Pen. He was the only Confederate brigade commander captured in the battle. Union Colonel Charles H. T. Collis, of the 114th Pennsylvania, won the Medal of Honor by saving the artillery from Atkinson’s men.

The beauty and pageantry of both armies had been torn and bloodied in the fields around Prospect Hill and the Slaughter Pen. The battle had resulted in 9,000 casualties – 5,000 Northerners and 4,000 Southerners – scattered in the woods, marshes, and open fields. The losses equaled those in front of Marye’s Heights, where the Union army counted 8,000 casualties to the Confederates’ 1,000. Once Burnside had lost the struggle against Stonewall Jackson, there was nothing he could do to win the Battle of Fredericksburg. Everything else had become a foregone conclusion. When Abraham Lincoln heard the news of Fredericksburg, he moaned, “If there is a place worse than hell, I’m in it!” His political stock had reached its nadir. So had Burnside’s reputation and Lincoln soon replaced the Union commander with Major General Joseph Hooker. Though victorious, General Robert E. Lee was moved by the awful destruction in the Slaughter Pen. When he contrasted Meade and Gibbon’s magnificently tailored ranks with the shattered commands retreating across the fields, he whispered to James Longstreet: “It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.”

Frank A. O’Reilly is a historian in the Fredericksburg area, and is the author of The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003). His work has received numerous literary awards.